A bad end to a tumultuous year for Serbia-Kosovo relations

22 November 2018

Pristina’s decision to put 100% tariffs on imports from Serbia and Bosnia will be economically disruptive, and marks a step back for normalisation of relations in the region.

On November 21st Kosovo announced a new 100% tariff on imports from Serbia and Bosnia. In addition, the government instructed authorities to stop goods entering Kosovo that did not use the country’s constitutional name (Republic of Kosovo).

On November 6th Kosovo had already put 10% tariffs on imports from the two countries, with Pristina claiming that Serbia and Bosnia were waging an “aggressive campaign” against it. Increasing tariffs to 100% came after Kosovo failed on November 20th for the third time in three years to gain enough support to join Interpol. The Kosovan government blamed its failure to get the required 2/3 support of current members on lobbying efforts by Serbia.

Mapping out the trading relationship

The initial decision to put 10% tariffs on imports from Serbia and Bosnia violated the terms of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), of which all three countries are members. Both Serbia and the EU said that the decision should be revoked. Federica Mogherini, the EU’s High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, also made it clear that she felt Kosovo’s move violated the spirit of the EU-Kosovo Stabilisation and Association Agreement.

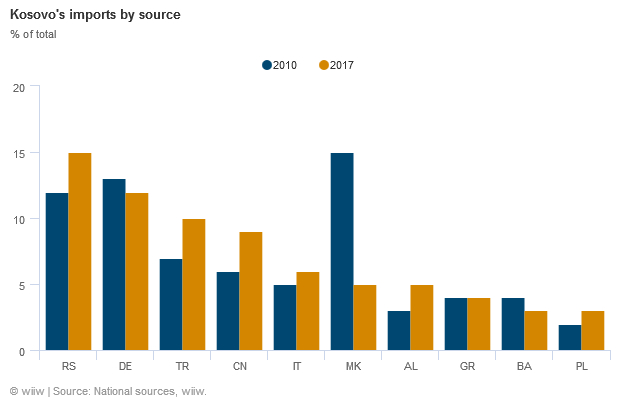

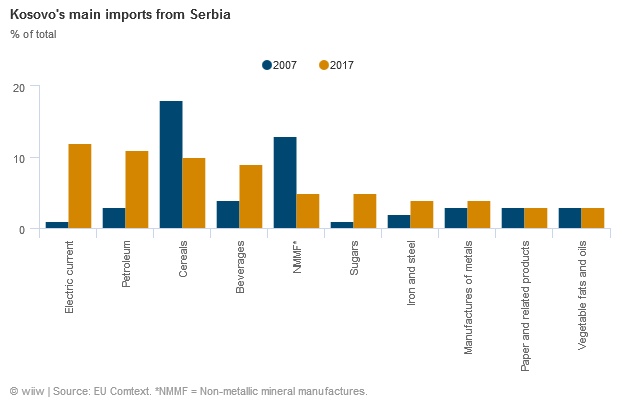

The economic implications could be quite significant. Serbia is Kosovo’s main source of imports, accounting for around 15% of the total as of 2017, while a further 3% come from Bosnia (see chart below). Interestingly, the Serbian share has actually increased since 2010, when it was around 12%. In 2017 the other key sources of imports were Germany (12% of the total), Turkey (10%), China (9%) and Italy (6%). Together, imports from Serbia and Bosnia account for over 8% of Kosovo’s GDP. Unless replacements can be found, therefore, an impact on inflation from the measures is quite likely (albeit probably not especially significant). Kosovo’s main imports from Serbia are electricity, petroleum (and related products), cereals and beverages.

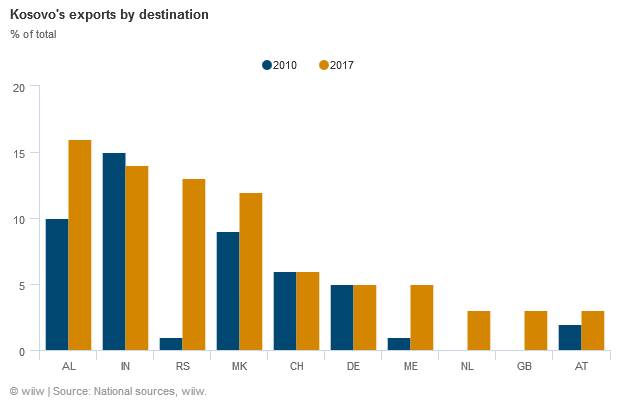

So far there has been no talk of retaliatory measures, but if they were introduced that would also have important trade implications for Kosovo. Serbia is Kosovo’s third biggest export market, taking 13% of the total in 2017 (see chart below), with a further 2% going to Bosnia.

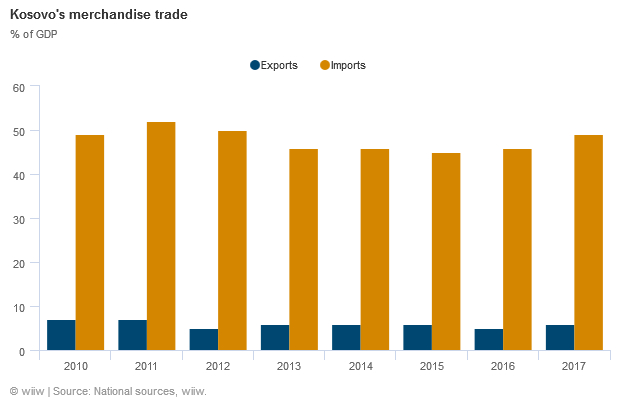

In terms of merchandise trade, the Kosovan economy is very closed on the export side. Exports/GDP are only around 6%, easily the lowest level in the CESEE region, and have not grown on this basis since 2010. Part of this is related to the country’s relatively disappointing progress on attracting more FDI inflows (as we detailed here). By contrast, imports/GDP are almost 50% of GDP, so disruption to import flows could have a much more important impact. We highlighted in our recent Forecast Report on Kosovo the potential for political risks, particularly in relation to Serbia, to weigh on growth in the near term.

From the perspective of Serbia and Bosnia, there is also clearly potential for disruption, although for both countries exports to Kosovo make up a fairly small share of the total. Official data indicate that merchandise goods exports to Kosovo account for around 1% of Serbia’s GDP and 0.5% of Bosnia’s.

A lively year for Serbia-Kosovo relations

Kosovo and Serbia have been engaged in dialogue to resolve bilateral issues under EU sponsorship since 2013. Progress has been underwhelming, but there was renewed hope in mid-2018 related to talk about a possible land swap between the two countries. This however fell apart, in line with our expectations. Our view was that the domestic barriers to making the necessary concessions on both sides would be insurmountable, and this proved to be the case.

The tariff hike has the potential to further increase tensions between the two countries, and suggests that the process of political normalisation between them has gone backwards. However, the renewed engagement of the EU in the region, and especially the focus under the Commission’s new Western Balkans strategy to intervene more directly in political conflicts in the region (rather than hoping that greater economic integration would solve bilateral disputes), is likely to prove an important stabilising factor. In economic terms, Serbia is clearly one of the frontrunners among the Western Balkan countries for EU accession, but Brussels has made it clear that joining the bloc is contingent upon normalisation of relations with Kosovo. We continue to view the Commission’s 2025 target date for accession, at least for Serbia and Montenegro, as highly ambitious (see our paper here).

photo: iStock.com/Enrique Ramos Lopez