Iran’s structural challenges and available policy options

11 April 2019

The government is in a very difficult position, owing to both domestic and external factors. Better cooperation with the EU should be a priority.

By Mahdi Ghodsi

- Recent major floods have added to a daunting list of challenges facing the Iranian government, which include a deep recession and high inflation.

- The weakness of the economy and surging cost of living over the last decade have significantly reduced the spending power of the Iranian middle and lower-class.

- Iran is also under pressure from the US, which has pulled out of the nuclear deal. Recently, the US also designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), an elite branch of the armed forces as a foreign terrorist organisation. This will have serious economic consequence for Iran and cargo and oil shipment through the Persian Gulf.

- Against this backdrop, improving relations with other foreign (and specifically EU) countries would help. The government should attempt to end four decades of animosity with the West by pursuing a less confrontational course.

- A more conciliatory tone should be adopted, in order to attract businesses and partnerships through INSTEX, a new EU-Iran payment vehicle to facilitate non-dollar trade.

- In addition, European governments should offer Iran loans and aid, to help offset the current loss in oil revenue.

- Iran should tackle corruption by improving regulation in the economy and finally joining the FATF.

Iran started the fiscal year 1398 (beginning March 20, 2019) with a government budget that expanded from the last year by about 40% (i.e. around the year-to-year inflation) in domestic currency. As in the previous year the Iranian rial depreciated by about 250%, the new budget is significantly contractionary in US dollar terms, envisaging a recession period. A recent report by the World Bank predicts a 3.8% contraction of real GDP in 2019, 0.2% stronger than the previous forecast published in October 2018. The most significant expansions in the budget was allocated to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and their related semi-public companies, as Iran fears geopolitical instability induced by the US. However, the budget to the official army and some other government entities like the Guardian Council of constitution has shrunk. Moreover, wages and employment expenditure of the government (around 80% of the total) has only increased by about 20%, implying a fairly significant reduction in real terms.

Huge loss of spending power for most citizens

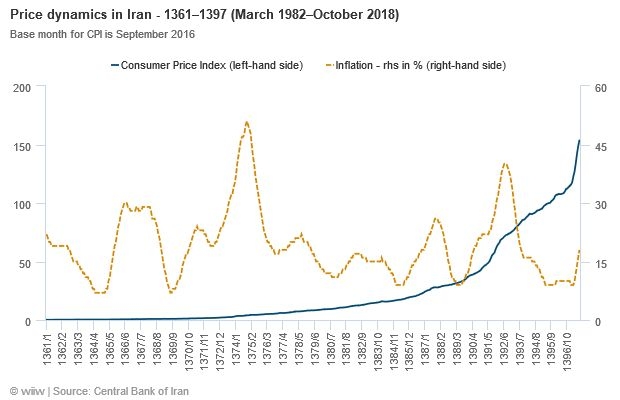

During the past decades, due to high inflation and recessions, Iranian spending power has shrunk enormously. In particular, those on fixed contracts or who are employed by the public sector (around 4m people, 15% of active population) have lost tremendously. Governments and parliaments simply neglected the spending power of these people since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 when setting the minimum wages and increases of their salaries in the annual budgets of the government. The consumer price index (CPI) increased by 348% from 33.1 in the seventh month of 1389 (October 2010) to 148.4 in the same month of 1397 (October 2018), where the base month of CPI (100) is in September 2016 (Figure 1). However, the salary of a representative public pensioner increased by only about 130% during the same period.

This does not reflect the policies of one single government. Rather, it essentially shows that both the executive branch of government and the deep state comprising other entities in the republic have lacked serious economic expertise, governance, and management of the economy. This has in turn led to discontent among citizens.

Major floods add to challenges facing the country

The new Iranian year started with an unfortunate natural disaster across the country, causing capital and human losses, which will definitely exacerbate the forthcoming recession. Flash floods hit the north east, the western mountainous areas, the western south plains, and the central ancient city of Shiraz. As reported by many and known by all Iranians, these floods could have been much less disastrous if the authorities had not allegedly and unwisely exploited vegetation and forests, and had not ruined the ancient watercourses on the streams of flood around these parts of the country.

Sanctions having a big impact

Long-standing US sanctions, which have mostly been followed by other advanced economies and US allies, have been another key factor causing economic difficulties. Although the current US leadership makes this particularly challenging, the Iranian authorities should try to resolve this animosity and dissuade other countries from imposing sanctions (something that has not been achieved over the past 40 years). Four decades of animosity should be tackled by extending the hand of friendship to any country. While the JCPOA was being negotiated between the US State Department and Iran foreign ministry, some high-level officials in Iran continued undermining the US government, and stated their animosity in public speeches and military exercises. These actions were significant in prompting hawkish rhetoric around Iran from the Republican side during the US presidential election campaign, and in particular negative attitudes towards the nuclear deal. US President Donald Trump’s subsequent decision to withdraw the US from the JCPOA has cost the Iranian oil and gas industry $200bn.

In the first month of 2019, three European signatories of the JCPOA – namely France, Germany, and the United Kingdom – established the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that was promised by EU High Representative/Vice President Federica Mogherini to facilitate barter trading of Iran against the new US sanctions. This mechanism, along with the updated Blocking Statute, enables companies to initiate trade and investment relations with Iran without fearing US penalties, as they will be compensated by the European Courts enforcing the Blocking Statute against the US sanctions. Although large multinational enterprises would not put themselves in such trouble by choosing Iran over the US, it is still possible that Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) with no economic relations with the US could benefit from economic relations with the big market of Iran. However, the Iranian authorities should not expect that firms in other parts of the world and in market economies listen to any political leader or governments as semi-public companies do in Iran or China. Rather, these firms simply maximise their profits and minimise their costs, while considering political risks.

Recently, further pressure has been put on Iran by the US, with sanctions being placed on the elite IRGC on April 8th. This is the first time that part of a country’s military has been labelled a terrorist organisation in this way. The decision by the US will increase Iran’s difficulties, especially considering that the IRGC is currently providing aid to areas of Iran affected by flooding. Moreover, the IRGC and its affiliates are heavily involved in different sectors of the economy, such as construction, infrastructure, petroleum, transportation, finance and banking, and telecommunication. Any firms doing business with IRGC-linked groups in these sectors now risks the threat of sanctions.

This will additionally provoke military tensions in the region. The IRGC has an advisory role, troops, and extensive support from governments across Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria, which has intensified in the past years in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham (Levant) ISIS. In retaliation, Iran has also designated the United States Central Command (Centcom) in the region as a terrorist organisation, which could have serious consequence for the passage of US navy, oil and other commodity shipments through the Persian Gulf.

Policy priorities for the Iranian government

The situation that Iran finds itself in is extremely difficult, and the challenges that the authorities face should not be underestimated. However, much of what happens next remains in their hands, and they can achieve a more positive outcome for the country by implementing sensible policies. In particular, three things stand out:

First, the government needs to present a friendly face to international business. In order to attract foreign investment, one needs to offer warm words, open policies, and political stability. Sarcasm at the very top level of the Iranian government, in particular recent ones with regards to Europeans, needs to be converted to smart, coherent, and homogenous diplomatic policy. Insults and death threats by politicians and the public are only signs of weakness, and have caused mainly animosity towards Iran in the past four decades. With INSTEX, a fruit of good diplomacy, Iran can also improve its economic relations with third countries like Iraq and Turkey. For instance, Iran could import products from Europe and act as a transit hub to re-export and transport those products to land-locked neighbours and Central Asian countries.

Second, the government should seek to obtain credit and aid from European partners, in order to finance the sustainable development of the country. As European governments cannot sufficiently incentivise private companies to initiate economic relations with Iran, they should offer credits and aid to the Iranian government to expand its budget during these difficult times. As mentioned above, a large portion of Iranians are struggling with a hefty cut to their real incomes, and need support from the government. Ideally, the government should initiate an expansionary fiscal policy to expand infrastructure, public transportation, water, and energy and power networks. This could both stimulate employment growth in the short-run, and contribute to better welfare, sustainable development, environmental quality, and air pollution reduction in the long-run.

Recent US sanctions have reduced Iran’s exports of oil to less than 1m barrels per day, compared with more than 2.8m in April 2018. This will be reduced even further after the US waivers expire by May 2019. This loss of revenue could be at least partly offset by obtaining European loans and aid. This should be one of the last resorts of the support from the European signatories of the JCPOA to keep Iran abiding by its obligations, which will potentially assist Iran to offset some of the negative impact of sanctions, and satisfy development policies at home. The Iranian government debt to GDP hovers around 44% and its external debt to GDP was only around 2.4% in 2018, which indicates good conditions for borrowing. However, concrete planning and feasibility studies on how to spend such loans should be developed with the assistance, verification, and surveillance of European creditors, preventing any corrupt efforts of the rent-seekers.

Third, as an important step towards internationalisation and ending self-isolation, Iran’s un-modernised banking system should modernise and become more transparent by joining the financial action task force (FATF). A lack of transparency, sanctions, subsidised double pricing, and the economic power wielded by some political actors are the major causes of rent-seeking behaviour and corruption and their related scandals. These need to be resolved for Iran to enjoy economic prosperity. Corruption should be stopped ex-ante from the roots by sound and reasonable regulations rather than by the ex-post hard penalties.

Although the legislation related to joining the FATF has passed through its conventional channels – namely the executive government, the parliament, and the Guardian Council of the constitution – its final effective enforcement is hindered by the main political pillar of the Republic at the Expediency Discernment Council. In order to finally join the FATF, Iran is required to subscribe to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and its protocols, known as the Palermo Conventions. While Iran supports the fight against trafficking of humans, women, and children, and also smuggling of the migrants through land, sea, and air – the first two protocols of the Convention – it is worried about the third protocol, against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts and Components and Ammunition. Over the past four decades Iran has become self-sufficient in the manufacture of arms and ammunition by importing technology from non-conventional sources, as it was left without support during the eight year war with Iraq. Iran has thus legitimate security concerns in the troubled region of the Middle East, which oblige it to not follow the third protocol and obtain its own arms, while some of its regional rivals are supplied by the US. This concern should be addressed by the international community in establishing a regional arms-deal that allows Iran to have access to conventional international arsenals, while other country’s military activities and expenditures are also constrained by the deal. When Iran subscribes fully to the Palermo Convention, this will additionally allow it to sustain and empower its defence and deterrence military policy. However, with the recent designation of the IRGC as a foreign terrorist organisation by the US administration, Iran joining the FATF will be too far to achieve.

photo: istockphoto/claffra