Decoupling of productivity from wages: a phenomenon of the Central European manufacturing core?

07 July 2020

Experiences of productivity-wage decoupling in Central and Eastern Europe are diverse, but strongly linked to the countries’ industry structure.

By Joris M. Schröder

photo: iStock.com/RainerPlendl

- Over the analysed period from 2002 to 2017 all Central and East European members of the EU (EU-CEE11) have experienced growth in labour productivity, but trickle down to local workers in the form of compensation and wage growth has been questioned (Bohle, 2018).

- In the EU-CEE11 countries, patterns of wage-productivity decoupling reflect the different growth paths that countries followed after EU integration and their corresponding industry structure.

- Countries that, relative to other EU-members, specialised in manufacturing have experienced productivity-wage decoupling that is equally explained by a declining labour share and by worsening terms of trade for workers.

- Countries specialising in the provision of services, on the other hand, are characterised by “negative decoupling” (compensation growing faster than productivity), which is almost equally explained by an increasing labour share and by improved terms of trade for workers in these countries.

'A rising tide should lift all boats' has been one of the central claims in the extensive debate on the decoupling of productivity growth from wage growth in the US (Economic Policy Institute, 2019). As labour productivity grows, so should the “typical” worker’s compensation (measured by median compensation). But at least in the case of the US, the two measures started to decouple in the 1970s.

Most of the Central and East European members of the EU (EU-CEE11) have experienced growth in labour productivity following their integration into the EU and the euro area (Leitner and Stehrer, 2019). However, trickle down of increased labour productivity to local workers in the form of compensation and wage growth has been questioned (Bohle, 2018). Recent analyses show that the extent of decoupling between labour productivity and wages varies strongly between EU-CEE11 countries. However, they provide little explanation as to why the gains in productivity are (not) fully passed on to compensation growth, and why this is more pronounced in some countries than in others (Theodoropoulou, 2019). These questions are addressed in our recent research report.

What underlies productivity-wage decoupling?

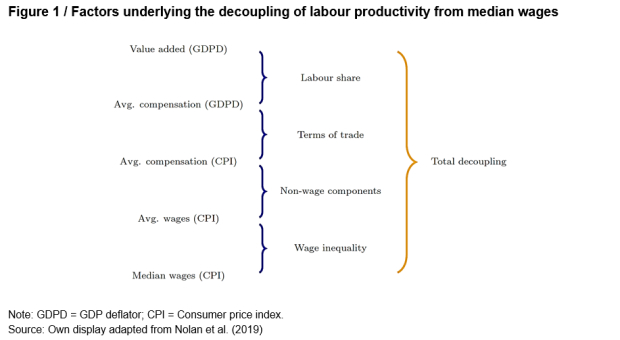

In the literature four developments emerge as the most important factors in explaining the decoupling of labour productivity from the typical worker’s gains from employment (see Figure 1). These are changes in the labour share of income, changing terms of trade, the growth of non-wage components of compensation, and wage inequality (Feldstein, 2008; Nolan et al., 2019; Stansbury and Summers, 2018). Many of these developments are tightly linked to the development of a country’s industry structure, and they also vary between sectors within countries (Karabarbounis and Neiman, 2014; Stöllinger, 2016; Verhoogen, 2008).

Two stories of decoupling in Central and Eastern Europe

In Central and Eastern Europe we can see that patterns of wage-productivity decoupling reflect the different growth paths that countries followed after EU integration and their corresponding industry structure. While some Central and Eastern European countries specialised in manufacturing, others de-industrialised quickly (Bohle, 2018; Stehrer and Stöllinger, 2015; Stöllinger, 2016).

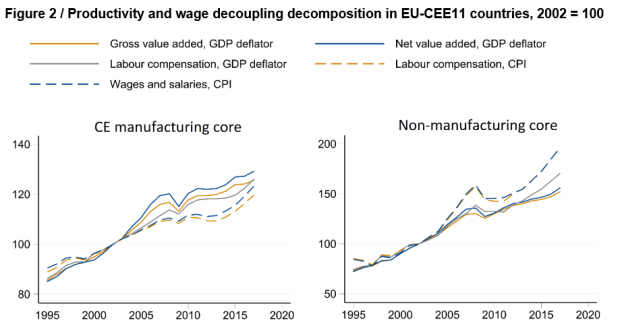

Note: Depicted are the unweighted averages of the growth rates within countries of the Central European manufacturing core (Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) and the remaining EU-CEE11 countries except Croatia (Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, Slovenia). Sectors B-S excluding O are used as proxy for the total economy. Net value added = GVA minus capital depreciation.

Sources: EU KLEMS Release (2019); national accounts (Eurostat, 2019) and SES (Eurostat, 2020); own display.

In the countries of the Central European manufacturing core (including Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland) productivity has grown faster than compensation throughout most of the analysed period, from 2002 to 2017 (see Figure 2). The gap between productivity and wage growth shrank during the economic crisis and then widened before shrinking again in recent years, owing to strong compensation/wage growth on the back of rising labour shortages. Throughout this period the decoupling of compensation from productivity is equally explained by a declining labour share and by worsening terms of trade for workers. In our research report we show further that wage inequality and the slower growth of non-wage components of compensation play a smaller role in overall decoupling, and that decoupling appears much more pronounced within industry and construction than in the services sector owing to slower productivity growth in the latter.

A very different picture emerges for the countries that are not part of the Central European manufacturing core (see Figure 2). These countries are characterised by “negative decoupling”, with compensation/wages having grown faster than productivity. This negative decoupling is almost equally explained by an increasing labour share and by improved terms of trade for workers in these countries between 2002 and 2017. The sectoral breakdown in our research report further shows that negative decoupling can mostly be attributed to an increasing labour share and improved terms of trade for workers in the services sectors of these countries.

Although these aggregated results still obfuscate considerable cross-country variation in wage-productivity decoupling, they reveal an important link to countries’ growth regimes and industry structures and provide some insights for joint policy efforts. First, the fact that compensation growth has broadly followed productivity growth in most countries highlights the importance of measures aimed at increasing productivity. However, a second general implication of the productivity-wage decoupling literature has been that wages – particularly median compensation and wages – should play a central role besides productivity measures for monitoring living standards and inclusive growth (Nolan et al., 2019). Our analysis reinforces these findings with regard to the EU-CEE11 countries, and in particular those countries that belong to the Central European manufacturing core, where wage growth has often failed to keep up with productivity growth.