On a 20-year journey towards a global gold-standard in trade

23 July 2019

This month marks the first anniversary of the EU-Japan trade agreement. Initial effects are already observable. However, its full implementation still lies 20 years ahead of us.

By Julia Grübler

photo: iStock.com/daboost

- The Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between the EU and Japan was signed in July 2018, and entered into force on the 1st of February 2019.

- EU trade with Japan – and particularly imports from Japan – grew strongly during the first months of the EPA’s application.

- The biggest trade effects from tariff cuts are to be expected for the agricultural and food sectors. Negotiated tariff reduction schedules, however, span over two decades.

- At the core of EU-Japan trade relations are the transport sector, machinery and electronic equipment, for which the reduction of non-tariff barriers is even more important.

- The inclusion of safety, labour and climate issues fortifies the EU’s and Japan’s standing in global standard-setting fora.

The Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between the EU and Japan was signed one year ago – on 17 July 2018 at the EU-Japan summit in Tokyo. It entered into force on 1 February 2019, surprisingly quickly for an agreement of this type. It is considered the most ambitious EU trade agreement with any Asian economy.

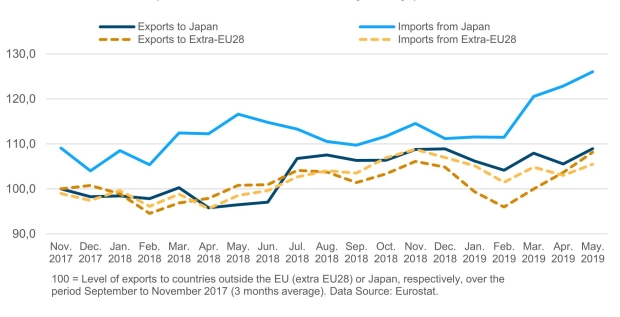

EU exports to Japan picked up already last year, while imports have soared during the first months of 2019, suggesting that the EPA may have already had an impact. The increase in trade flows with Japan indeed appears more pronounced compared to trade with other economies outside of the EU28, particularly on the import side (see chart below).

Graph 1: Goods trade of the EU28 (Index on the three months moving average)

Reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers over two decades

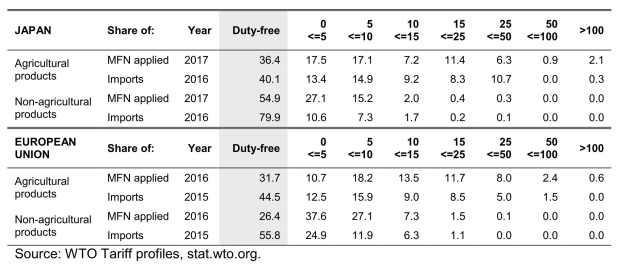

Many products entered the Japanese and EU markets duty-free already prior to the establishment of the EPA. 36% of all agricultural products and 55% of industrial products faced no duty when exported to Japan from another WTO member, such as the EU. Likewise, a zero-tariff applied to 32% of agricultural and 26% of industrial goods exported to the EU from other WTO members, such as Japan. Shares of duty-free imports were even higher.

Since the agreement came into force, 90% of the EU’s exports to Japan are no longer subject to duties. Although tariffs between the EU and Japan are already at a comparatively low level, the schedule for further tariff reductions to cover 99% of EU tariff lines and 97% of Japanese tariff lines is quite comprehensive (Annex 2-A on tariff elimination and reduction is a document of 236 pages; the agreement itself counts 562 pages).

Table 1: Tariff profiles of Japan and the EU prior to the EPA

Shares of tariff lines and shares of imports for different tariff rates

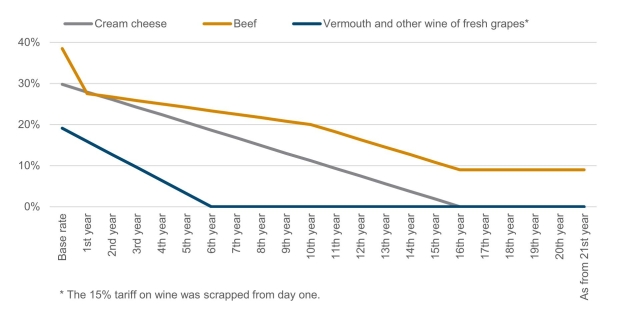

The tariff reductions are likely to have a significant impact on the EU’s agricultural sector. The Commission mentions products for which it assumes the biggest gains for Europe. In the agricultural and food sectors a boost in exports of pork, beef, wine, cheese and processed products such as pasta, chocolate, candies or tomato sauce are expected.

However, the speed at which tariffs and non-tariff barriers are reduced by both parties varies by product. Schedules are outlined for a period of 20 years after the agreement’s entry into force. Although many trade liberalisation steps are taken during the first years of its application, the full potential of the EPA will only materialise after two decades.

Furthermore, tariff cuts are more complex than is often assumed. For example, glucose and glucose syrup containing added sugar are targeted with a tariff of 85.7% or 60.90 yen/kg (whichever is greater). For this product a tariff rate quota was agreed upon (TRQ-13 scheme), increasing the aggregate quota quantity which can enter the Japanese market without duty from 1,780 metric tonnes in the first year to 5,340 metric tonnes for the 12th year and thereafter. Imports exceeding the quota are subject to customs duties unaffected by the EPA. In general, stepwise reductions, mixed tariffs and safeguard clauses arise in more sensitive sectors, e.g. agriculture, which are given more time to adapt to trade liberalisation.

Graph 2: Examples of ‘easy’ tariff schedules

Setting a “global gold-standard”

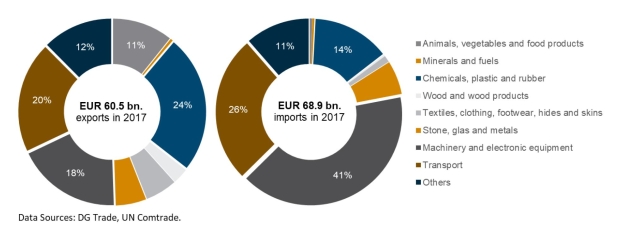

Roughly 40% of EU exports and more than 60% of EU imports are machinery, electronic equipment and goods related to the transport sector. For these, an agreement on applying the same international standards – regarding product safety, environmental protection and quality management systems – play a more crucial role than tariff cuts. This is because they make double testing and certification unnecessary, thereby reducing non-tariff barriers to bilateral trade. For example, Japan is aligning its standards for cars and car parts to vehicle regulations laid out by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), which also form the basis for EU standards.

Graph 3: EU exports and imports to and from Japan in 2017

The EPA with Japan also covers sensitive topics so far underrepresented in trade agreements. Out of 296 agreements covered by the Trade Agreement Heterogeneity Database (TAHD), only 86 include trade in services, 85 cover investments, 66 address environmental topics and 43 agreements tackle labour issues.

- Services trade: Specific sub-sections of the EU-Japan EPA deal with the regulatory framework of postal and courier services, telecommunication, financial and maritime transport services as well as e-commerce. It is worth noting that the EU has a surplus in services with Japan, largely offsetting the negative balance in goods, despite trade volumes in services being much lower than those of goods.

- Investment: The aim of increasing investment is repeatedly emphasised in the EU-Japan EPA. The focus is on increased transparency, market access, national treatment and corporate governance, but does not include investment protection standards and the topic of dispute resolution. Negotiations on these matters for a separate agreement are ongoing.

- Environment and labour: Chapter 16 of the EU-Japan EPA is dedicated to trade and sustainable development. It reaffirms the importance of labour standards put forth by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the commitment to multilateral environmental agreements such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992) and – for the first time in an EU trade agreement – the Paris Agreement (2015).