The EU’s peripheral role in China’s global vision

14 December 2017

The Belt and Road Initiative creates global opportunities and challenges. Though hotly debated in the EU, geographically and economically, the core of the strategy lies in Asia.

A commentary by Julia Grübler and Robert Stehrer

Photo: Chensiyuan, CC-BY-SA 4.0

- The Chinese BRI is a project spanning Eurasia and Africa, with global implications.

- The BRI is not necessarily compatible with the visions of other major players in Eurasia, such as ASEAN, Japan or India.

- Chinese engagement in Europe constitutes only a small part in its global vision. BRI investment in the ‘16+1’ region in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE) is small compared to overall foreign direct investment (FDI) or EU transfers to the region. The biggest Chinese FDI inflows are observable for other EU Member States, particularly the EU Big-3: Germany, France and the UK.

- The EU will not play a pivotal role in the BRI as long as there is no coordinated response to the Chinese investment initiative. There is a risk that the lack of a common strategy could speed up the political divergence process between EU members in the West and the East.

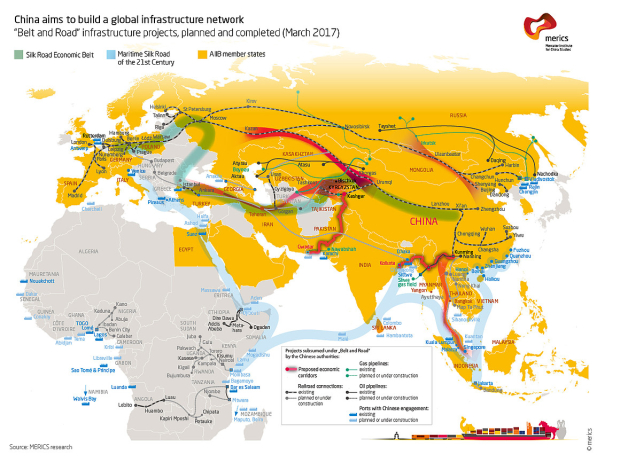

The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – also known as ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR) initiative or the ‘New Silk Road’ – is a global project. Up to 65 countries along the economic belt on land or the maritime road might become part of this mega-project. Even if the initiative is not a Chinese development strategy for Eurasia, it may actually turn out to be a major growth driver for participating countries, particularly for less developed regions between the two endpoints: China and the EU. It provides funding for much-needed infrastructure investments, thereby stimulating domestic income, demand, economic growth, trade integration and potentially political cooperation.

The geographical scope of the BRI

Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies (merics).

Obviously, the BRI also serves Chinese interests. In part, China has chosen to undertake the BRI initiative in response to being excluded from inter-regional trade deals negotiated in recent years (among them the TPP and TTIP), and more recently rising protectionist rhetoric by the US. Domestic reasons include the need to reduce overcapacities that have built up in sectors such as the steel and construction industries. Investment in transport and energy infrastructure along the economic belt (i.e. the land route) will allow China to diversify its trade routes and export destinations, access energy and raw materials, and develop its poorer western provinces and economically as well as politically unstable neighbouring regions.

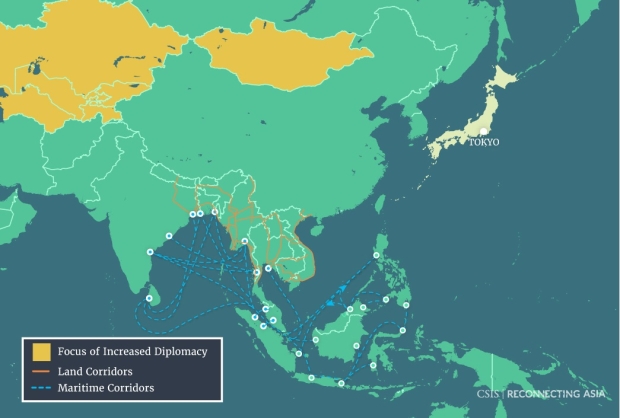

However, there is also the risk of tensions due to competing infrastructure investment plans by other major players in Asia. The Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), for example, has identified nine other infrastructure priorities for leading actors in the region. China’s BRI has to be seen in the context of:

- The vision of the Association of (ten) Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to better connect its member states and India,

- Iran’s ambitions to become a transit hub in a North-South corridor running from Moscow to Mumbai with connections to Europe and Asia,

- Japan focusing on improving its connections to Southeast Asian countries,

- Russia’s vision for the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) aimed at linking it to the BRI and increasing connectivity to Central Asia,

- South Korea’s outreach to Europe, ASEAN and Russia,

- Turkey’s plans to build roads and railways strengthening its connections with Asia and Europe.

- India is mostly engaged in improving infrastructure and transport networks within its own borders.

- European Union efforts focus on expanding the already well-developed Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) complementing the Euro-Mediterranean and Eastern Partnership and improving the connectivity with China’s BRI.

To which extent these visions or plans are mutually consistent is a matter of discussion, as is the question of whether the opportunities related to the large-scale Chinese infrastructure investment plan prevail over the risk of tensions, conflicts or even war in Asia.

Japan’s Vision of infrastructure investment in Asia

Source: Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS); Reconnecting Asia.

For the EU, China is a trade giant but still an investment dwarf

In Europe the recent ‘16+1’ summit attracted a lot of attention, but more for political than economic reasons. The 6th meeting of the ‘16+1’ country formation – consisting of 11 EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe and five countries in the Western Balkan region – took place on 27 November 2017 in Budapest. Economic opportunities stemming from Chinese infrastructure investments were highlighted by politicians of the ‘16+1’ group. However, these still need to materialise – many projects were announced but very few have so far entered into the construction phase.

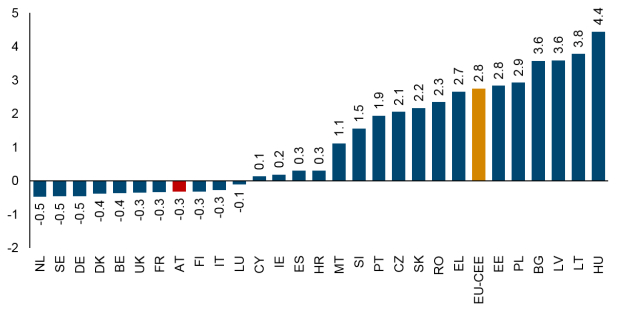

So far, the value of Chinese investment in the region is minimal compared with EU investment and transfers. China accounted for just 1.3% of FDI inflows to the ‘16+1’ region in 2015. Inflows from Austria alone amounted to 9.1% that year. The stock of Chinese FDI in the ‘16+1’ accounted for 0.1% of total FDI in 2015, compared to 11.3% of Austrian FDI (Data: wiiw FDI Database). Chinese investments so far also appear economically negligible when compared to the size of EU cohesion funds in the region. The average operating budgetary balance (i.e. the difference between payments to the EU budget and payments received from the EU budget) over the period 2011-2015 ranged in size from 1.5% of Slovenian GDP to 4.4% of Hungarian GDP.

Operating budgetary balance in % of GDP, average for the period 2011-2015

Source: European Commission; wiiw Research Report.

Efforts have been made to come up with a common EU position towards the BRI, but they are yet to bear fruit. Among the initiatives are the Connectivity Platform to discuss China’s contribution to the European Fund for Strategic Investments (ESFI), the EU-China strategy, and negotiations on a EU-China investment agreement (the next round of negotiations take place this week), featuring the debate on EU public procurement regulations. Meanwhile, not officially related to the BRI but to economic relations with China in general, are ongoing discussion about the way the EU implements renewed trade defence instruments, and the envisaged stronger screening of foreign investment within the EU. This was announced by Jean Claude Juncker in his speech on the State of the Union (13 September 2017):

“Let me say once and for all: we are not naïve free traders. Europe must always defend its strategic interests. This is why today we are proposing a new EU framework for investment screening. If a foreign, state-owned, company wants to purchase a European harbour, part of our energy infrastructure or a defence technology firm, this should only happen in transparency, with scrutiny and debate.”

Overall the EU appears cautious with regard to China and the BRI. While EU members outside the ‘16+1’ circle are the main recipients of Chinese FDI, they question the feasibility of BRI plans, and fear both the dominance of Chinese firms and workforce in the proposed infrastructure projects, and an undermining of EU regulations. So far, Chinese investment has played a limited role in countries within the ‘16+1’ club. These countries have argued strongly for more Chinese engagement in the region, and some are increasingly using the BRI for Eurosceptic and populist political agendas. If the lack of a coordinated approach towards China and the BRI persists, the EU will lose the opportunity to actively shape the BRI and profit from infrastructure investments, but might instead face a speeding-up of political divergence within the EU.