20 years after the EU’s Eastern enlargement: charting a path for sustained economic success

11 June 2024

With the right industrial policies, the EU members in CEE can become a more strategic player in EU value chains, increase their resilience and close the remaining gaps with Western Europe

image credit: istock.com/metamorworks

Introduction

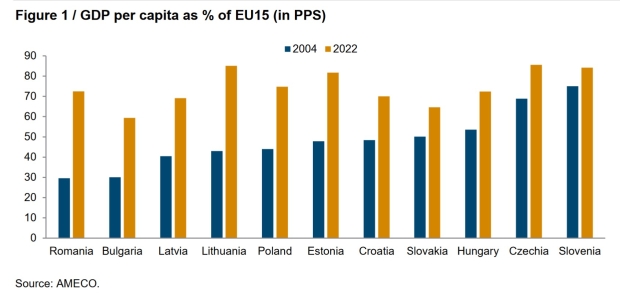

In modern history, there are not many countries that have experienced development as dynamic as the Central and Eastern European member states of the EU (EU-CEE) in the years leading up to and following EU accession. In less than two decades, these countries have gone from having GDP per capita as low as 30% of Western European levels to over 70% today (see, for instance, Romania in Figure 1). One can also observe in Figure 1 that countries such as Czechia or Slovenia, which benefitted from better starting positions compared to other CEE countries, are now virtually as economically developed as most Western European nations.

Firgure 1 - GDP per capita as % of EU15 (in PPS)

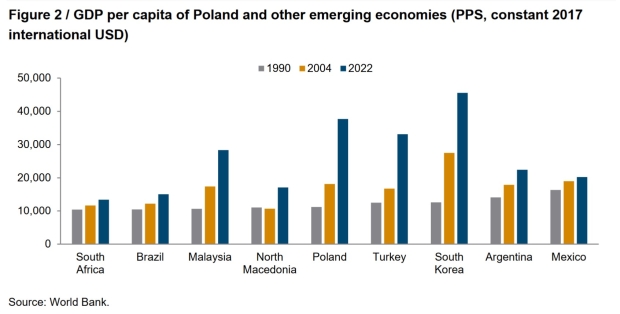

To some extent, it is to be expected that less developed countries will catch up with more advanced ones, as it is consistent with various economic theories of convergence.[1] When one benchmarks the region’s growth against more economically comparable countries, the remarkable nature of this becomes all the more evident. Taking Poland as an example, Figure 2 shows that, in 1990, the country had a GDP per capita level roughly comparable to those of South Africa, Brazil, North Macedonia and Turkey. In the years that followed, however, Poland strongly surpassed all these major economies with similar starting points, with the exception of only South Korea, another growth champion.

Figure 2 - GDP per capita of Poland and other emerging economies (PPS, constant 2017 international USD)

The role of EU membership in fuelling the economic success of EU-CEE is well known and well documented. As the necessary institutional reforms were undertaken by the then-candidate countries and as trade barriers between ‘new’ and ‘old’ member states were dismantled, foreign direct investment (FDI) poured into the region to take advantage of its cost-competitive, skilled labour force. As a result, the EU-CEE countries became important nodes in international production networks, particularly in manufacturing sectors of medium-high technology.

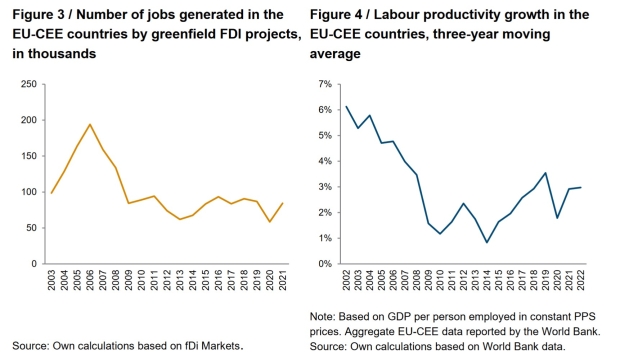

Yet, 20 years on, the need to transition away from this FDI-based growth model is looming large on the EU-CEE countries. Especially following the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, the job-generating potential of FDI has been fading, and labour productivity growth has never recovered to its pre-crisis levels (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). Consequently, the notion that the low-hanging fruits stemming from EU membership have already been reaped is spreading across EU-CEE, necessitating a strategic reorientation to a new, more innovation-driven growth model (see Grieveson et al. 2021 for a detailed discussion on this topic). However, the region’s success in this next growth chapter will crucially depend on its ability to tackle numerous challenges as well as to embrace various opportunities that await it along the way.

Figure 3 - Number of jobs generated in the EU-CEE countries by greenfield FDI project, in thousands

Figure 4 - Labour productivity growth in the EU-CEE countries, three-year moving average

Challenges

Regional disparities

Although the economic progress made over the past 20 years was undoubtedly significant, the gains have certainly not been shared equally. Regional disparities continue to be a pressing issue in the EU-CEE context, with certain parts still lagging very far behind in terms of industrial development and having standards of living far below the EU average. Generally speaking, EU-CEE’s capitals now boast GDP per capita levels high above the EU average, including 207% in the capital region of Czechia (Praha), 177% in the capital region of Romania (Bucuresti-Ilfov), and 162% in the capital region of Poland (Warszawski stołeczny).[2] These regions also display signs of more sophisticated specialisations in global value chains, taking on activities beyond just production and assembly (Kordalska et al. 2022). On the other hand, the GDP per capital levels of the poorest regions in these three countries respectively stand at 60%, 46% and 54% of the EU average.[3] While the EU’s Cohesion Policy tackles precisely this challenge, the pace of development has nevertheless been uneven, requiring stepped-up regional policy efforts on the part of EU-CEE governments in the years ahead. After all, as long as a significant portion of the EU-CEE population is being left behind, the previous stage of development cannot yet be considered complete.

Institutional environment

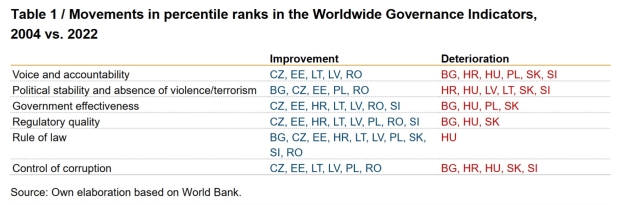

Particularly in recent years, the EU-CEE region has been struggling with institutional backsliding. In two countries of the region, Hungary and Poland, this has even led to a temporary suspension of the disbursement of EU funds (which is still ongoing in the case of Hungary). Worryingly, the World Governance Indicators (WGIs) reveal deteriorations in the percentile ranks in 2022 compared to the EU enlargement year of 2004 in multiple countries. The divergence between economic growth and the gains from it – fuelled by the above-mentioned regional disparities – potentially acts as a contributing factor, fostering populist tendencies that, in turn, contribute to the erosion of institutional integrity. Hungary shows the worst performance in this regard, having deteriorated in all six dimensions of the WGI compared to almost 20 years ago (Table 1). Slovakia and Bulgaria are not faring much better, as they show deteriorating tendencies in five of the six dimensions. By contrast, Czechia, Estonia and Romania have improved across all dimensions.

Considering that institutional reforms were a crucial factor in EU-CEE’s economic success following EU accession and that the institutional setting should generally improve as economies develop, this is certainly a distressing trend. Furthermore, given that the leap to a more innovative economic model fundamentally requires capable governments along with well-designed and -implemented policies, the competitiveness of multiple EU-CEE countries may be under serious threat.

Table 1 - Movements in percentile ranks in the Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2004 vs. 2022

Demographics

Another significant challenge relates to people – or, more precisely, a lack thereof. The issue of labour shortages has been long discussed in EU-CEE, and it’s clear that there are no quick solutions to the problem (see e.g. Astrov et al. 2022). Strikingly, the EU-CEE labour markets have remained largely resilient to the multiple economic shocks of the past four years, with the issue of labour shortages persisting even amid recessionary developments. Survey results[4] indicate that the share of firms experiencing shortages of labour surpasses 30% in the manufacturing sector of Poland, 25% in the case of Slovenia, and 20% in the cases of Slovakia and Hungary. Together with the Netherlands, these are the most labour-constrained countries of the EU. Generating economic growth under conditions of labour scarcity will be a difficult yet necessary task for EU-CEE going forward. This will inevitably require policies to maximise labour market participation, to promote inward migration while mitigating outward migration, and to incentivise family formation.

The green transition

The exposure of the EU-CEE countries to the changes brought on by the green transition is high, yet so far their preparedness for the transition remains low. While progress has been made on a number of fronts, including the decoupling of growth from CO2 emissions and improvements in energy efficiency, there is still a long way to go to reach the ambitious goals of the European Green Deal. Given three main factors – namely, that the region’s energy mix is heavily skewed towards non-renewable sources, that societal recognition of the climate crisis is lower than in most other parts of the EU, and that a notable share of the population is employed in brown sectors, such as coal mining and the production of combustion engine vehicles – getting the EU-CEE economies ready for the green transition will certainly not be an easy task (see Riepl and Zavarská 2023). Yet an apprehensive stance towards the transition risks making matters worse. After all, whether EU-CEE adapts or not, the world is already moving in the direction of developing cleaner technologies and adopting renewable energies. Hence, failing to embrace the green transition and effectively utilise the relevant financial instruments and policy mechanisms available in the EU comes with the risk of economic obsolescence, with outdated industries struggling to remain relevant in a changing world.

Opportunities

Automation and digitalisation

A promising means for inducing an upgrading of EU-CEE economies and dealing with the demographic challenges can be found in the automation of routine tasks. As argued by Grieveson et al. (2021), instead of perceiving this transformation as a threat, there are opportunities to be found in the EU-CEE countries that argue in favour of a wider adoption of automation technologies, which channels scarce labour into value-adding activities that cannot be easily carried out by robots. At the same time, in the digital realm, certain countries (particularly in the Baltics) and certain sectors (e.g. software or e-commerce) in EU-CEE have already demonstrated considerable potential. Moreover, even in countries that are falling behind in terms of digitalising the wider economy, there are local competitive firms emerging in the digital economy that could pave the way for new industries to thrive (see Zavarská et al. 2023). In this sense, the digital transformation – in contrast to the green transition – can be regarded as an area in which some leapfrogging could take place in the years ahead, thereby positioning the EU-CEE countries as ‘digital challengers’ in the EU context (McKinsey 2022).

The EU’s industrial strategy and Open Strategic Autonomy

Today’s world is starkly different from the one of the early 2000s, when the EU-CEE countries joined the EU. While the former period was characterised by ‘hyper-globalisation’, what we have been observing in recent years is a slowdown in these integrative forces and a changing policy tone of all major global economic actors (e.g. Antràs 2020). The EU is no exception in this regard, as it has announced its intentions to pursue Open Strategic Autonomy – which, as summarised by European Commission Executive Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis, entails ‘acting multilaterally wherever and whenever we can, but being able to act autonomously if we must’ (European Commission 2021).

Under this reference framework, a number of EU instruments have been introduced, including massive financing from the NextGenerationEU fund, a number of changes to state aid rules, investment screening mechanisms, and initiatives like the European Chips Act and the Net-Zero Industry Act. All of these mechanisms are meant to strengthen EU-centric value chains in critical and strategic sectors. While operating in a multipolar world comes with a multitude of challenges, the EU-CEE countries – as integral participants in the EU’s manufacturing value chains – can also stand to gain from the more assertive stance of the EU. This holds true not only from the perspective of potential value chain restructuring and the increased appeal of near-shoring that it may bring, but also from the perspective of the growing policy and financial space available to boost the resilience and competitiveness of EU industry. Compared with other emerging countries in the world, this puts the EU-CEE countries in an advantageous position, as they can leverage the joint financial and policy space with some of the most technologically advanced countries of the world.

EU enlargement

Another EU-wide development that EU-CEE could leverage to its advantage comes from the potential enlargement of the EU to include the Western Balkan countries, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. The fact that the EU-CEE countries would move from the position of ‘new’ member states to ‘old’ member states raises several important questions related to competitiveness. On the one hand, the newly integrated countries would hold a significant labour cost advantage, which could impact the currently strong positions of the EU-CEE countries as assemblers in EU value chains. On the other hand, it is precisely this type of shock that could induce the EU-CEE countries to upgrade their positions in these value chains. This process could resemble the ‘flying geese’ pattern observed in the development of East Asian countries, whereby less sophisticated products and segments of value chains were shed by certain countries as they developed and passed on to less developed countries in the region (see Kojima 2000). Such a regional transmission of industrialisation in the European context would entail having the EU-CEE countries finally cede their strong specialisation in the production stage of the value chain, which far exceeds levels that would be in line with their development levels in the first place (Stöllinger 2021). At the same time, stronger integration of candidate countries into the EU could induce more outward FDI activity from the EU-CEE countries into these countries, creating new possibilities for EU-CEE-centred value chains to emerge.

Industrial policy for EU-CEE’s next growth chapter

Without a more active and strategic use of industrial policy, the opportunities discussed above are unlikely to materialise and the challenges will only be compounded.[5] Indeed, a contributing factor to the productivity slowdown evident in Figure 4 relates to the passivity of EU-CEE’s growth path to date, which can only take countries so far. Hence, without policies to help induce structural change, it will be very difficult for them to move away from their positions as dependent market economies (Nölke and Vliegenthart 2009). At the same time, as more and more EU member states move in the direction of implementing their own industrial strategies, the EU-CEE countries will need to keep pace with them to avoid divergence in economic performance as much as possible.

Thinking about modern-day industrial policy for EU-CEE, a number of core pillars can be identified (see Zavarská et al. 2023 for more details). First, states need to play a more proactive role in connecting key actors in the economy, including the private sector, academic institutions, key ministries and business development agencies. It is based on these interactions that promising areas and niches can be identified and exploited. The EU-CEE countries need to be careful not to equate industrial policy with top-down planning, as witnessed in parts of the region in recent times. At the same time, the EU-CEE countries can and should learn from the achievements of each other (as well as of other countries). For instance, the success of some EU-CEE countries in the digital sphere can serve as an inspiration to the wider region. However, replicating policies without sufficiently considering the unique conditions of each country runs the risk of policy failure. Hence, each EU-CEE country needs to create a tailor-made strategy that is a good fit for its specific needs and ambitions.

Second, given that the EU-CEE countries are members of the EU, it is imperative to think about having an industrial policy that not only is compatible with EU rules and regulations, but also makes the most of this integration. Importantly, this means making better use of EU funds than the region has done up to now, such as by improving their absorption and efficiency. At the same time, boosting participation in the EU’s expanding range of joint research and industrial policy initiatives could offer the EU-CEE countries valuable opportunities to learn from more technologically advanced countries. Yet, without targeted support, it remains difficult for local actors to participate.

Third, if EU-CEE wants to go beyond its current role as an assembler in value chains, it needs to rethink the way it approaches FDI promotion. Specifically, investment promotion schemes need to be closely tied to industrial innovation strategies of the EU-CEE economies while also avoiding blanket support to foreign investors and overly generous subsidies. Indeed, both domestic and foreign firms should be supported based on their potential contribution to the local economy, and any support should be adjusted and scaled back over time. Furthermore, deeper linkages and spillovers between foreign and domestic actors need to be promoted.

Fourth, as discussed above, there is a worrying trend in the area of institutional quality in many of the EU-CEE countries. Given these circumstances, institutional improvements and reforms need to go hand in hand with industrial policy endeavours. Without it, the EU-CEE countries run the risk of fostering overweening policies, corrupt practices and distortive interventions. Yet, as the successful experience of East Asian countries reveals, having institutional quality at the level of the countries of Northwestern Europe need not be a prerequisite for the successful implementation of industrial policies, provided that accountability mechanisms are put in place. Instead, institutional improvements and industrial development can go in tandem, creating a virtuous cycle between these two spheres.

Finally, more efforts need to be dedicated to balancing structural change with equality. In this context, EU-CEE nations can strive for flexible labour markets to facilitate the shift from traditional to modern sectors and job opportunities, complementing this process with robust retraining initiatives and a comprehensive social safety net to ensure that individuals or entire regions do not get left behind. Considering the major regional imbalances present in EU-CEE, a more place-sensitive and regionally oriented industrial strategy is paramount not only for making the pie larger, but also for making the pieces more equal.

Conclusion

The past two decades have been a truly transformative time for the EU-CEE countries, which is in large part a consequence of EU accession. Looking to the years ahead, the EU-CEE region has a lot to gain from further deepening its integration with other European nations. A more assertive EU, which is putting its own competitiveness at the core of its economic strategy and potentially expanding its internal borders, will open up unique opportunities for EU-CEE to transform into more a strategic player in European value chains. At the same time, given the region’s relatively favourable starting positions, leveraging technological developments and newly emerging sectors in the digital sphere can pave the way for new specialisations of EU-CEE countries.

On the other hand, decoupling the region’s growth from fossil fuels and creating a greener economy will require concerted efforts and sound reskilling and redistribution mechanisms. The shortage of labour will also need to be tackled, such as by leveraging possibilities for automation and tapping into segments of the labour force that face greater obstacles to participation, such as female, young, elderly and foreign workers. Rising populism and declining institutional quality threaten to make the challenges harder and the opportunities less accessible. Nevertheless, with the right set of industrial policies and firm commitment, EU-CEE can upgrade its position in EU value chains, increase its resilience to external shocks, close the remaining gaps with Western Europe and, ultimately, enhance the well-being of its populations – thereby setting the stage for another successful 20 years.

Footnotes:

[1] See, for instance, Quiroga (2007) for an overview.

[2] This is partially also driven by firms registering in capital cities but maintaining operations across different parts of the country, which overstates the concentration of economic activity in capital regions.

[3] 2022 data, taken from Eurostat (nama_10r_2gdp).

[4] Labour shortages limiting production in Q4 2023 (Source: DG ECFIN).

[5] This section draws on the findings and insights presented in Zavarská et al. (2023).

References:

Antràs, P. (2020), ‘De-globalisation? Global value chains in the post-COVID-19 age’, National Bureau of Economic Research No. w28115.

Astrov, V., R. Grieveson, D. Hanzl-Weiss, S. Leitner, I. Mara, H. Weinberger-Vidovic and Z. Zavarská (2022), ‘How Do Economies in EU-CEE Cope with Labour Shortages? Study Update from wiiw Research Report 452’, wiiw Research Reports, No. 463, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), Vienna, November.

European Commission (2021), Remarks by Executive Vice-President Dombrovskis at the press conference on the fostering the openness, strength and resilience of Europe’s economic and financial system, 19 January, Brussels.

Grieveson, R., A. Bykova, D. Hanzl-Weiss, G. Hunya, N. Korpar, L. Podkaminer, R. Stehrer and R. Stöllinger (2021), ‘Avoiding a Trap and Embracing the Megatrends: Proposals for a New Growth Model in EU-CEE’, wiiw Research Reports, No. 458, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), November.

Kojima, K. (2000), ‘The “flying geese” model of Asian economic development: origin, theoretical extensions, and regional policy implications’, Journal of Asian Economics, 11(4), 375-401, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1049-0078(00)00067-1.

Kordalska, A., M. Olczyk, R. Stöllinger and Z. Zavarská (2022), ‘Functional Specialisation in EU Value Chains: Methods for Identifying EU Countries’ Roles in International Production Networks’, wiiw Research Reports, No. 461, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), August.

McKinsey (2022). Digital challengers on the next frontier in Central and Eastern Europe. Report. 14 September.

Nölke, A. and A. Vliegenthart (2009), ‘Enlarging the Varieties of Capitalism: The Emergence of Dependent Market Economies in East Central Europe’, World Politics, 61(4), 670-702, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887109990098.

Quiroga, P. A. B. (2007), ‘Theory of Convergence’, in: P. A. B. Quiroga, Theory, History and Evidence of Economic Convergence in Latin America, Instituto de Estudios Avanzados en Desarrollo (INESAD), 6-20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00574.

Riepl, T. and Z. Zavarská (2023), ‘Towards a Greener Visegrád Group: Progress and Challenges in the Context of the European Green Deal’, wiiw Policy Notes, No. 64, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), January.

Stöllinger, R. (2021), ‘Testing the Smile Curve: Functional Specialisation in GVCs and Value Creation’, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 56, 93-116.

Zavarská, Z., A. Bykova, R. Grieveson, D. Hanzl-Weiss and O. Sankot (2023), ‘Industrial Policies for a New Growth Model: A Toolbox for EU-CEE Countries’, wiiw Research Reports, No. 469, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), July.