A new EU strategy for the Western Balkans

10 June 2022

A new wiiw study shows that the primary focus of the EU’s strategy towards the Western Balkans should be to ensure higher incomes in the region.

- A change in the EU’s strategy towards the Western Balkans is long overdue - the current strategy has failed to deliver regional economic integration, has resulted in meagre progress towards EU accession, and has generated disappointment in the region.

- A new wiiw study draws lessons from the EU accession process of the Central and Eastern European EU member states (EU-CEE) for the Western Balkan economies.

- EU accession has increased trade in goods and services between EU-CEE countries by 50%.

- The main channel for this process has been the income channel - higher GDP per capita has increased the demand for and the supply of products from the region.

- The most direct way that EU accession has increased incomes in EU-CEE has been through EU budget transfers.

- The main implications of these findings for the Western Balkans are clear: The best way to improve regional cooperation in the region is through policies aimed at raising incomes. The most direct way for the EU to achieve this would be through higher budget transfers.

- The war in Ukraine is only strengthening these arguments: as Western Balkan citizens may become even more disappointed by the EU if there is no change in its approach, it could open the doors for even greater Russian influence.

No “more of the same”

The Western Balkans looks like an appendix of the EU. None of the six economies – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia or Serbia – is an EU member, and they all seem to be light years away from it. So far only Serbia and Montenegro have started accession talks, while North Macedonia and Albania have been waiting for 18 and 13 years respectively.

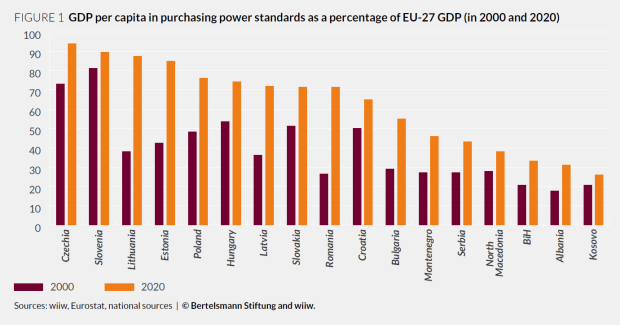

Instead of granting the countries full membership, the EU strategy towards the Western Balkans has so far relied on improving regional economic integration. Some of the efforts in this respect have been Bilateral Investment Treaties, Free Trade Agreements, and the Berlin Process, which was supposed to lead to a Common Regional Market. While these efforts may have improved intraregional trade and investment to some extent, standards of living are lagging behind not only those of the older EU member states, but also those of the new member states from Central and Eastern Europe (EU-CEE). There is also an increasing sense of disappointment in the region about the EU, driven by the impression that the EU does not believe in enlargement anymore and that some countries do not really want the Western Balkans to join.

Figure 1 - GDP per capita in purchasing power standards as a percentage of EU-27 GDP (in 2000 and 2020)

Thus a change in the EU’s strategy for the Western Balkans is long overdue. “Business as usual” will not only fail to improve things, but will likely add to a growing sense of frustration. Against this background, the new wiiw study “The long way round: Lessons from EU-CEE for improving integration and development in the Western Balkans” aims to draw lessons for the Western Balkan economies from the EU accession process of the Central and Eastern European EU member states. More precisely, it investigates to what extent regional economic integration improved in EU-CEE after EU accession, identifies the reasons for this, and determines which lessons can be drawn for the Western Balkan economies.

What can be learned from the EU-CEE for the Western Balkans?

The study finds that EU accession has indeed improved regional economic integration in EU-CEE. Trade in goods and services within this region increased by approximately 50 percent due to the countries’ EU accession. Integration in terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) also improved after EU accession, albeit to a lesser extent, and no evidence could be found there for a direct link to EU accession, although there might have been indirect effects, through the higher incomes brought about by EU accession.

The dominant means by which EU accession improved intraregional trade integration in EU-CEE was the income channel. By increasing incomes in the region, EU accession boosted demand for and the supply of goods and services from other countries in the region, which in turn increased intraregional trade.

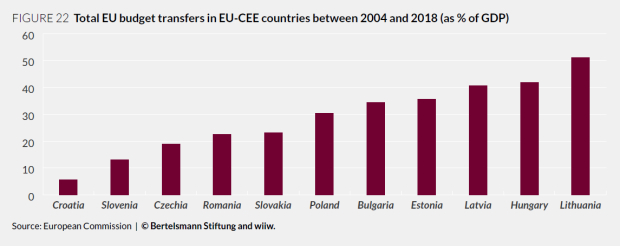

The most direct way that EU accession has increased incomes in EU-CEE has been through EU budget transfers, not FDI. On average, these countries have received transfers from the EU budget equivalent to 2 percent of their GDP per year. In recent years, the amounts have been higher, and some of the countries, such as the Baltic countries, Hungary and Bulgaria, have received even more (roughly 3 percent). The analysis points out that doubling annual transfers (i.e. increasing them from 1 percent to 2 percent of GDP) leads to an impressive overall increase in GDP of 14 percent. We also find that higher government spending, stronger FDI inflows, greater political stability and better institutions also increase incomes. It is very likely that EU accession positively influenced most, if not all, of these factors in EU-CEE.

Figure 2 - Total EU budget transfers in EU-CEE countries between 2004 and 2018 (as % of GDP)

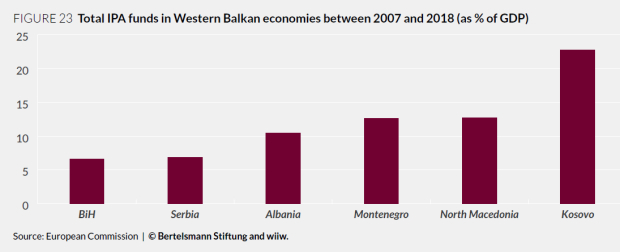

Figure 3 - Total IPA funds in Western Balkan economies between 2007 and 2018 (as % of GDP)

What should a new EU strategy towards the Western Balkans look like?

The main implication is that the most effective way to improve regional cooperation within the Western Balkans is through policies aimed at raising incomes. Higher incomes will lead to greater demand for goods and services from within the region, to greater supply and, in turn, to greater regional economic integration.

One direct way for the EU to achieve this is to increase budget transfers to the Western Balkans. This could be done by granting the Western Balkan economies full access to the EU budget. The costs of this for existing EU member states would be marginal, i.e. less than 0.05% of each country’s GDP, while the effects for the Western Balkan economies would be substantial.

For this to have the biggest possible impact, greater transfers should be accompanied by strict conditions for institutional reform. Without better institutional quality and governance standards, the Western Balkans will not be able to absorb any increase in EU funding.

The Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans which the EU adopted in October 2020 is similar to previous EU support for the region and will therefore not be sufficient. Its planned size of €9 billion is equivalent to around 1 percent of the Western Balkans’ collective GDP per year. In practice, the disbursed funds would be even smaller. They will thus be very similar to previous versions of the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (i.e. IPA I and IPA II), both of which failed to make any significant impact. This is much smaller than what the EU-CEE countries will receive from Next Generation EU, where the amounts range between 3 to 5 percent of their GDPs, every year.

Fast EU membership must remain the priority, as the war in Ukraine shows

These proposals do not imply that the EU should not grant full membership to the Western Balkan economies soon. That should remain the priority number one. North Macedonia and Albania must open accession talks as soon as possible, preferably this year, and the integration of the other economies should be one of the EU’s highest priorities. The unique aspect of these proposals is that they call for full access to the EU budget before the Western Balkan countries become full members of the Union.

The war in Ukraine further reinforces the urgency and relevance of our argumentation. If the EU continues its slow and ambivalent strategy towards the Western Balkans, it will only feed disappointment with and scepticism towards the EU in the region, threatening to turn it into a geopolitical football pitch. As Russia will obviously not give up its strategic interests in the region, growing EU scepticism means only one thing – greater space for Mr. Putin to spread his influence across the region. This can lead to massive destabilisation not only of the Western Balkans, but also of the wider region. The best strategy for the EU to prevent this is by showing to the region that it cares for it, by providing greater support than before.