Challenges and potential opportunities for the EU steel industry in the face of US tariffs

27 March 2025

The European steel industry is under increasing pressure. Trump's new 25% tariffs are further undermining its competitiveness. The European Commission views this industry as vital for Europe’s defence and rearmament. Francesca Guadagno and Robert Stehrer on the current state of the industry, the potential consequences of US tariffs and the EU's retaliation

image credit: istock.com

By Francesca Guadagno and Robert Stehrer

Even before US President Donald Trump imposed new tariffs of 25% on the European steel industry, it had come under severe pressure over the last few years for various reasons. Two of them have been fierce global competition and high energy prices in the aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Despite these adverse circumstances, the European Commission (EC) believes that having a strong steel and metals industry will be vital for Europe’s defence capabilities and its recently announced plans[1] to rearm Europe’s militaries in order to enable the EU to defend itself without US support. This prompted the EC to introduce the ‘European Steel and Metals Action Plan’ on 19 March 2025.[2]

Revamping the industry’s competitiveness

Although its share is declining, the EU remains an important global player in these industries. In the basic metals industry (NACE C24), the EU has a share of around 25% of global value added, down from more than 27% in 2010. During this period, China increased its share from approximately 9% to 13%, while the US share declined from 5.4% to 3.9%. These shifts are even more pronounced in the fabricated metal products industry (NACE C25), where the EU’s share dropped from 41% to 33% between 2010 and 2022. In that same period, China’s share increased from 17% to more than 30%, and the US share declined from 6.7% to 4.7%. In terms of GDP, basic metals (NACE C24) and fabricated metal products (NACE C25) together account for slightly less than 2% of GDP in the EU, compared to about 4% in China and 1% in the US.[3]

These industries are of crucial importance in many respects. As discussed in the Action Plan and in the Transition Pathway for the industry, steel and metals are essential inputs for products related to the green and digital transitions as well as for defence- and space-related efforts. For instance, self-propelled artillery systems can contain up to 100 tonnes of steel.[4] At the same time, aluminium is strategic for applications such as wind turbines, solar photovoltaics (PVs), carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, light-emitting diodes, energy storage technologies and electric motors.

The above-mentioned ‘European Steel and Metals Action Plan’ generally aims to secure a competitive and decarbonised industry in Europe. More specifically, the objectives of the initiative are to: (i) ensure an affordable and secure energy supply, (ii) prevent carbon leakage, (iii) promote and protect European industrial capacities, (iv) encourage circularity, (v) de-risk carbonisation, and (vi) protect quality industrial jobs. The Action Plan aligns with the broader policy framework of regaining competitiveness and strengthening manufacturing capacities in the EU by leveraging the opportunities of the green transition, as proposed in the Draghi Report, the Competitiveness Compass and the Clean Industrial Deal. Safeguarding production in Europe is also becoming increasingly imperative amid rising global overcapacity.

Exports affected by US tariffs on aluminium and steel

An additional concern is the recent surge in US tariffs. On 12 March 2025, the US imposed tariffs of 25% on aluminium and steel imports, as announced on 10 February. One proclamation listed 167 affected steel products, and another proclamation listed 123 affected aluminium products.[5] These products reportedly covered USD 151bn in American imports (about 4.5% of total imports) in 2024. In 2023, the leading exporters of these products to the US were China (USD 36bn), Mexico (USD 32bn) and Canada (USD 18bn).[6]

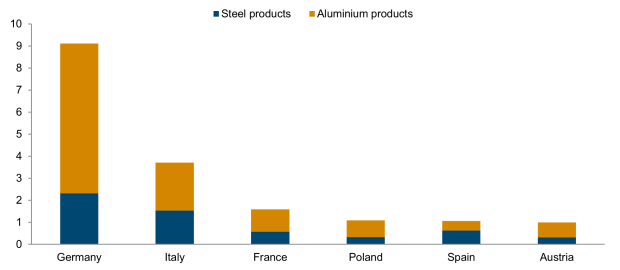

The EU exported USD 24bn of these products to the US, including USD 8bn in steel and USD 16bn in aluminium products. Germany was the leading EU exporter, with USD 9bn, followed by Italy, France, Poland and Spain. Austria exported steel products worth USD 0.3bn and aluminium products worth USD 0.7bn (Figure 1).

Figure 1 / US imports of aluminium and steel products affected by tariff hikes from the top 6 EU member states, 2023, in USD bn

Source: UN COMTRADE, own calculations.

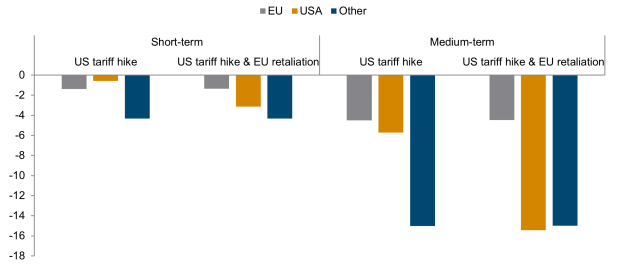

In Figure 2, we model the impact of the US tariff hike on the fabricated metal products (NACE Rev. 2 C25) in a partial equilibrium setting (marked as ‘US tariff hike’).[7] We also present the results of a scenario in which the EU retaliates against the US by imposing tariffs of 25% on this industry (marked as ‘US tariff hike & EU retaliation’), distinguishing between the short and the medium terms.[8]

In this scenario, EU exports would decline by 1.4%. While US exports would be scarcely affected, exports from all other countries would decrease by around 4%. In the medium term, the effects on exports would be more significant (as quantities respond more strongly to price changes), with EU exports declining by more than 4%.

The EU is currently assessing the best way to respond to Trump’s new tariffs. If the EU were to retaliate with tariffs of the same magnitude on US imports in this industry,[9] the impact on EU exports would remain largely unchanged compared to the scenario in which only the US imposes tariffs. In other words, the EU would gain little from such a policy in both the short and long terms. In contrast, if the EU were to put retaliatory tariffs in place, US exports would decline by 3% in the short term and by up to 15% in the medium term. Thus, EU tariffs would negatively affect US exports without significantly harming EU exports.

Figure 2 / Change in EU exports of the fabricated metal products industry, in %

Source: OECD TiVA; own model calculations.

Then, there is another critical issue. Our simulation shows that exports from other countries will drop by 4.3% in the short term and 15% in the medium term if the EU does not retaliate. But, crucially, the drops in exports will be almost identical if the EU actually does retaliate.

Rising strategic importance and challenges

Under the current geopolitical circumstances, the steel and metals industries – which rank among the hard-to-abate sectors – are becoming increasingly strategically important as well as globally challenged. For example, these industries are particularly impacted by high energy prices, which only make it harder for them to decarbonise. On top of that, the outlook for the EU steel and metals industries is bleak. The cost gap between EU producers and other global players has widened over the past few years, leading to declining production. The closure of production facilities, in turn, adds to the costs (e.g. by making restarts more expensive) and creates additional challenges in terms of loss of competencies and disruptions to supply chains (see Draghi 2024).

Another legitimate question is: If not to the US, where would the steel and aluminium products displaced from the US be redirected? These concerns add fuel to the debate surrounding tariffs and international competitiveness, not only for the directly affected industries but also for all other sectors that are closely linked to them. In addition, they raise questions about the EU’s broader strategic goals, such as reindustrialisation, the green transition and, more recently, defence.

To remain competitive amid global overcapacity, surging tariffs and the EU’s (rightly) ambitious decarbonisation goals, the EU steel and metals industry urgently needs policy support. But the importance of such support is even more far-reaching, as having a strong steel and metals industry is also essential to provide strategic inputs to other growing sectors.

Despite the current uncertainties and anxieties, there may be a thin silver lining for the EU. As US tariffs will make imported steel and aluminium less competitive in the US, steel products that were initially destined for the US market will now be forced to look for alternative markets – and the EU is one of them. Thus, US tariffs might not only penalise US industries that rely on these inputs but also offer the EU access to a wider range of products. Particularly for high-quality green products, EU downstream industries (i.e. industries that use steel, such as the automotive and defence industries) may be able to shop around at a time when demand is set to soar. This is the essence of the EU’s open strategic autonomy approach: producing more while ensuring that Europe can rely on a diverse range of high-quality trading partners.

References:

Draghi, M. (2024). The future of European competitiveness – Part B: | In-depth analysis and recommendations. September 2024.

Francois, J. & Hall, K. (2009). Global simulation analysis of industry-level trade policy: The GSIM model. IIDE Discussion Papers 20090803. Institute for International and Development Economics.

Footnotes:

[1] ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_25_793/IP_25_793_EN.pdf

[2] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_805

[3] Figures based on Eurostat/FIGARO Release 2024.

[4]See Action Plan (p. 1).

[5] This is according to the US HTS 8-digit classification system, which corresponds to the global HS classification system at the 6-digit level. The products for which tariffs are imposed include iron and steel products (included in HS article 73), aluminium products (included in HS article 76), miscellaneous articles of base metal (included in HS article 83), automotive and industrial components (included in HS articles 84 and 87), and furniture and kitchenware (included in HS articles 73, 76, 83 and 94).

[6] We corresponded the HTS 8-digit products to the HS 6-digit products. This implies that some products that are not subject to tariffs have been included in the analysis.

[7] The model is based on Francois and Hall (2009). The data are taken from the OECD TiVA database. We use this data instead of the trade flows, as intra-country trade – and, in case of the EU, intra-EU trade – are important.

[8] We assume low demand and supply price elasticities and low substitution effects for exports to partner countries in the short term (left quadrant) as well as higher price elasticities and substitution effects in the medium term. This is a typical assumption, as elasticities tend to become larger in the longer run.

[9] This is (still) only a hypothetical scenario, as the EU only announced that it will impose tariffs on a range of other products, such as whiskey and motorcycles (see https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_750).