Ex-Transition Economies’ FDI Recovery

26 July 2017

FDI recovers in former transition economies despite less favourable political environment. A commentary by Gabor Hunya.

The inflow of FDI had long been considered the main driver of economic growth in the countries of Central and Southeast Europe. During the transition to a market economy FDI provided much-needed capital and knowledge, as well as access to technology and markets. FDI boomed until the financial crisis and foreign investment enterprises became dominant in several countries, contributing to competitiveness and growth. In 2009-2014 investments declined all across Europe, including cross-border investments, due to the financial and euro crises. The EU Member States of Central and Eastern Europe (EU-CEE) were forced to rebalance their balance of payments to adjust to lower capital inflows and experienced low rates of economic growth for some years.

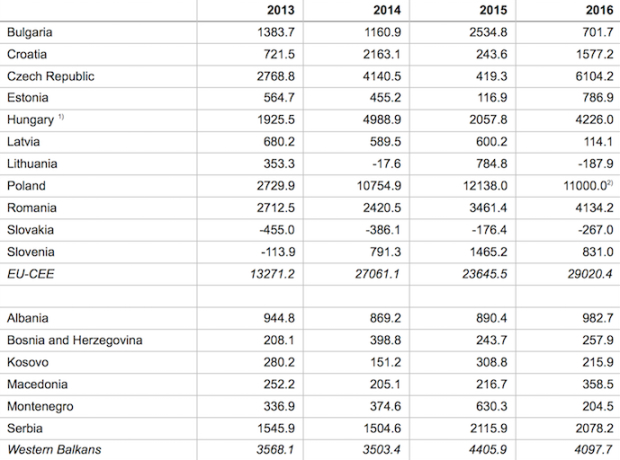

FDI inflows to EU-CEE took a strong upward turn in 2016, with an increase of 23% compared to the year 2015 (Table 1). The region experienced more robust economic growth than earlier while a lower but stable growth set in in the major investing countries including Germany. Although the Western Balkans experienced a modest 7% decline after a strong 2015, it has also become a solid target for foreign investors.

The 2016 surge of FDI in the EU-CEE region benefited mainly two counties, the Czech Republic and Hungary. Both of them received amounts that were the second largest since 2008 and surpassing the 2015 slump by a wide margin. Also Romania, Croatia and Estonia received higher amounts than the year before. (An amount similar to the previous year is expected for Poland.) Two countries reported negative FDI inflow values in 2016, Lithuania and Slovakia, due to higher capital withdrawals than gross inflows. (A more accurate picture is provided by data excluding capital in transit and company assets restructuring which are, however, only available for Hungary.) Most of the EU-CEE countries have been integrated into international value chains in the automotive, machine-building and electronics industries and remain attractive for outsourcing services via FDI.

In the Western Balkans, Serbia remained the most important FDI target in 2016 with inflows similar to the previous year. Albania received the second largest amount in this region on account of energy sector investments. In contrast, Bosnia and Herzegovina was less successful than in earlier years, probably on account of its increasingly segmented economic and regulatory environment. Macedonia received more FDI than the year before, despite mounting political uncertainty. In the Western Balkans FDI has been mainly confined to domestic market-oriented sectors with the exception of Serbia and Macedonia. Montenegro is a special case with high per capita FDI inflows focusing on real estate and tourism sector investments.

Taking the average of the past few years, the overall trend of FDI inflow is positive in both regions but shows no return to the high amounts of the pre-crisis years of 2005-2007. Meanwhile, the role of FDI in economic development has changed along with the attitude of governments towards foreign capital penetration.

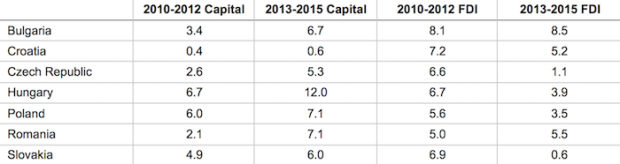

The recent economic recovery in EU-CEE is different from those before the crisis; it is based on household consumption and the inflow of EU structural and investment funds through the capital account of the balance of payments. EU funds have become a more important resource of external financing than FDI (Table 2). 2016 was a temporary exception when funding under the 2007-2013 period had expired and access to the funds under the 2014-2020 financing period was just at its outset. In addition to EU funds, domestic private and public capital has become strong and is shaping domestic economic policy more than it did before.

In view of more diverse sources of external financing and increasing economic nationalism, attracting FDI has become a less important goal of governments in EU-CEE than ten years ago. Administrative capacity has shifted to accessing EU funds. Distributed by accredited government agencies, these funds have improved infrastructure, the environment and supported mostly domestic SMEs. In another effort, governments have taken steps to support national champions such as the Czech energy company CEZ or the Hungarian oil company MOL to internationalise. Banking assets have become majority domestically owned in Hungary and Poland in the wake of direct political interventions and foreign investors have been pushed back in the media and the energy sector. A selective political attitude towards investors, favouring export-oriented ventures against domestic market access, has emerged also in other countries. The process has been supported by domestic oligarchs making deals with politicians.

Our forecast for FDI inflows in 2017 points upwards as economic growth in EU-CEE is bound to be more robust than in the previous year. Both consumption and investments recover and attract foreign companies. The EU-CEE countries have maintained cost competitiveness, despite surging wages and occasional labour shortages, by benefiting from considerable productivity improvements. The outsourcing of manufacturing and business services activities into the region continues, while domestic market shares of foreign affiliates are increasingly challenged by politically backed domestic companies.

Table 1 / FDI inflow, directional principle, EUR million

Remarks:

Data based on the IMF BPM6 directional principle; asset/liability data for Albania and Kosovo; data exclude Special Purpose Entities (SPEs), if reported.

1) Hungary excluding capital in transit and company assets restructuring.

2) Poland: estimated.

Table 2 / Capital account net and FDI net in % of GDP cumulated for 2010-2012 and 2013-2015

This analysis is based on Gabor Hunya (2017), wiiw FDI Report Central, East and Southeast Europe: Recovery amid Stabilising Economic Growth and was first published at emerging-europe.com.