FDI in Central, East and Southeast Europe: declines due to disinvestment

07 June 2018

New FDI Report reveals a strong downward turn of FDI inflow into the region. Renationalisation and domestic take-overs reduced FDI, especially in the EU-CEEs. Austrian FDI diminished, while investors' incomes increased.

By Gabor Hunya

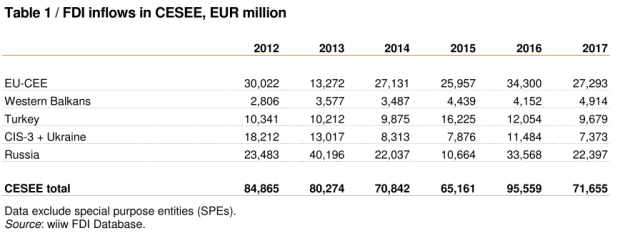

FDI inflows to CESEE declined by 25% in 2017, compared with the revised 2016 data. They were only EUR 72 billion, after the post-2008 record amount of EUR 96 billion the previous year (Table 1). The decline was 20% in the EU-CEE region and 36% in Belarus, Kazakhstan and Moldova (CIS-3) and Ukraine. The two most populous countries of the region also registered substantial declines: Russia -33% and Turkey -20%. Meanwhile, the Western Balkans achieved an increase of 18%. Despite adverse developments in most of the CESEE region, 2017 FDI inflows did not represent an outlier, but rather a return to the average of 2011–2015, exposing 2016 as an outlier.

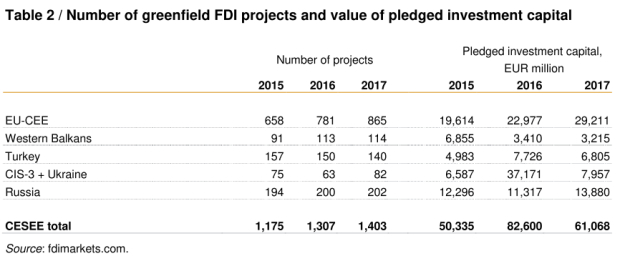

In 2017, CESEE witnessed increased greenfield FDI activity in terms of the number of projects (up 7.4%) for the third year in a row; meanwhile the amount of capital investment pledged fell 26% short of the extraordinarily high results for 2016 (Table 2, based on fdimarkets.com). The EU-CEE reported increases in terms of both project numbers and capital investment. The biggest greenfield investment boom was recorded in Poland, which also saw FDI inflow halved to EUR 5.7 billion in 2017 due to disinvestment.

Asset sales to domestic investors in the wake of disinvestment diminished the amount of FDI inflow (the net value of gross inflow and disinvestment). In Poland, UniCredit bank sold its 32.8% stake in Pekao Bank for EUR 2.4 billion to the state-owned insurance company PZU and the Polish Development Fund (PFR). In a wider context, the Polish government was engaged in taking domestic control (‘re-Polonisation’) of the financial sector and the media. In Hungary, too, foreign equity participations declined due to state acquisitions in the energy, telecom and banking sectors. As a result, almost the total FDI inflow to Hungary benefited the manufacturing sector. In the Czech Republic, domestic investors took over foreign assets in the media and telecommunications sector.

The EU-CEE and the Western Balkans may look forward to rising FDI inflows in 2018, thanks to buoyant economic growth. But FDI activity will not return to the pre-financial crisis level due to the subdued investment appetite of multinational companies. The scope for foreign takeovers is limited also in host economies where foreign affiliates produce 40–50% of GDP in the business sector – such as Hungary, Slovakia, Romania and the Czech Republic. In addition, political support for FDI focuses only on export-oriented investments with high-technology content; in other sectors domestic investors are strong and preferred competitors.

Labour shortage is an obstacle to new investments in the EU-CEE region. Greenfield investors face difficulties in meeting the employment demand for 220,000 new jobs to be generated by greenfield projects announced in 2017. In Hungary, foreign greenfield projects will absorb 90% of the potential new entrants to the labour market; in the Czech Republic and Poland – about 50%; in Slovakia and Serbia – 25%; and in Romania – 20%. As a comparison, foreign affiliates currently employ only about 25% of the labour force in these countries. The strained labour market situation may hinder further FDI, unless investors consider new options, such as automation or moving further to the east. The latter option is not very likely in the near future, as those eastern countries (such as Ukraine) provide inferior business conditions and infrastructure. The Western Balkans can provide alternative locations offering an underutilised labour pool and improving infrastructure.

Aside from business conditions in the region, there are several global developments that will shape FDI flows in 2018 and beyond. Sanctions on Russian oligarchs hit hard, triggering declines in both inward and outward Russian FDI in relation with the US and Europe. The USA’s corporate tax and profit repatriation reforms and its tariffs on steel and aluminium imports will channel global FDI flows to that country. If import tariffs on cars are applied to EU members, they will also hurt suppliers in CESEE. Brexit may imply a rethinking by foreign investors in Britain in terms of value chains or sunk costs and relocate parts of their activity. Digitalisation and industry 4.0 are expected to reduce the role of labour costs in splitting and locating the value chain, thus reducing the scope and size of globalised production. In this process, EU-CEE countries may lose some of their attractiveness as production sites in the long run, as automated production may not be sourced out any more.

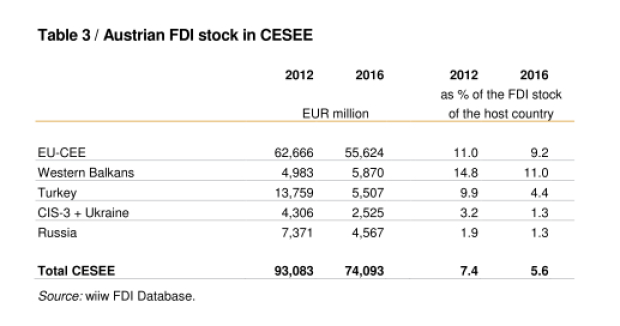

Austria remains the third most important immediate investor in the EU-CEE, after the Netherlands and Germany (9.2% of the inward stock in 2016) and the second most important in the Western Balkans (11%) (host country data; Table 3). Restructuring in banking (UniCredit) and other sectors has diminished the size of Austrian FDI stocks in the region. The significance of Austrian FDI is much lower in farther-away countries, such as the Baltic states or Russia.

Austrian direct investors enjoy above-average profitability in the EU-CEE. The region’s share in the Austrian outward FDI stock amounted to 25.5% in 2017, while it contributed 33% to the FDI income earned globally (OeNB data).

Austrian companies’ earnings in the EU-CEE amounted to 1.2% of GDP in 2017. This sum is much larger than Austria’s net contribution to the EU budget, which was 0.8% of GDP (2016). The relationship between the two is that a large part of the country’s payments to the EU budget has in fact gone on improving the infrastructure and the business environment in the EU-CEE and has helped Austrian (and other countries’) companies to earn profits on their investments in the region.

Press Releases

Related Presentations

- Rückgänge durch Kapitalabzug (press conference presentation in German)

- Declines due to Disinvestment (press conference presentation in English)