FDI in Eurasia: too little and from the wrong places?

05 April 2018

The post-Soviet space has not been very attractive for foreign investors, owing largely to a poor investment climate and frozen conflicts.

By Peter Havlik

- Both EAEU and DCFTA countries have been laggards with respect to attracting FDI, largely due to ‘frozen’ conflicts and a poor investment climate in general.

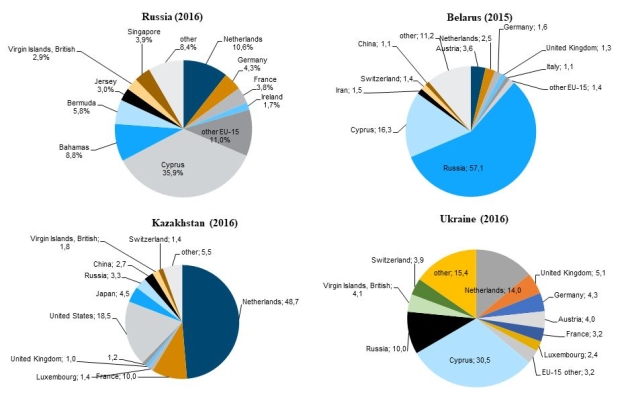

- An extremely high share of FDI into this region originates in Cyprus and other offshore destinations, suggesting a simple recycling of domestic flight capital.

- In contrast to Central and Eastern Europe, these FDI patterns are not and will not be conducive to export upgrading and economic modernisation.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been the main driver of restructuring and modernisation in formerly communist countries in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE). In Central and Eastern Europe, FDI has been instrumental in both privatisations of state-owned enterprises and in launching new investment projects. FDI flows in manufacturing have created modern, competitive, export-oriented industries and generated export revenues. However, FDI flowing into the services sectors (including finance and insurance but especially retail trade and real estate) have been more controversial, since they boost import demand rather than create new export opportunities.

Countries in the former Soviet Union have generally been laggards in terms of attracting FDI compared with other formerly communist counties in the region. This applies to both members of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), as well as those which recently signed a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU (Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova).

Global FDI flows are highly volatile and this applies to Eurasia as well. In 2016, FDI to Russia went up sharply, partly because of a single large transaction related to the oil company Rosneft; flows to Kazakhstan recovered as well. FDI flow into Ukraine also increased in 2016, primarily due to bank recapitalisations and the privatisation of some companies with the participation of institutional investors such as the EBRD. FDI flows to Georgia were relatively high in 2014-2016, presumably thanks to the implementation of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTA) established between the EU, and Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. A similar trend, albeit at a much smaller scale, was observed in Moldova.

FDI inward stock by key partners (%), Top 10

Cyprus as both origin and destination of FDI flows

DCFTA countries have generally struggled to attract a large amount of FDI, largely due to ‘frozen’ conflicts over disputed territories and a poor investment climate in general. Moreover, FDI in the DCFTA countries (similarly to Russia) have also a skewed geographic origin: in Ukraine, for example, more than 30% of FDI stocks originate in Cyprus; the share of FDI from Western Europe was just 36% of total FDI stocks in 2016. The extremely high shares of Cyprus and other offshore destinations indicate that this kind of FDI most likely just represents a recycling of domestic capital, and possibly also tax evasion. One can probably safely assume that this kind of FDI is not particularly conducive to upgrading and modernisation. Progress towards institutional reforms in general would therefore instead result in diminishing the shares of FDI that originates from offshore.

Modernisation and restructuring

The experience of EU countries in Central and Eastern Europe (EU-CEE) indicates that FDI inflows have significantly contributed to the modernisation and restructuring of their economies (about 80% of FDI there originates from Western Europe in contrast to less than 40% in Russia and Ukraine). FDI in the manufacturing industry, business services such as IT, and logistics, have been especially beneficial. Such investments have been particularly welcome as they help to establish competitive export-oriented industries (the successful German-CEE automotive cluster is a case in point). In the EU, foreign investors have to be treated in the same way as domestic ones. Recently, though, a renewed economic nationalism in some countries, such as in Hungary and Poland, has resulted in a selective discrimination of foreign investors, causing a de facto restriction of foreign investment in banking, trade, etc.

However, it is not just the volume of the registered FDI and its origin that matter; its sectoral composition, investors’ motives, and other FDI structural and ‘quality’ characteristics are also important. In EU-CEE, the bulk of FDI has been concentrated in manufacturing, trade, and financial services: each of these three broad sectors account for about 20-30% of total FDI stocks. In this respect, the DCFTA countries are not very different from Hungary, Poland, Romania, or Slovakia. As far as Eurasian Economic Union countries are concerned, most FDI has been concentrated in the energy and mining sectors (especially in Kazakhstan and Russia). In Moldova, Ukraine, and Romania, there are some (small) foreign investments in agriculture and, increasingly also in manufacturing. Apart from Russia and Kazakhstan, the energy sector is an important FDI target in Georgia, Moldova, and Romania (there are no comparable data for Belarus).

Investment climate matters

A number of factors clearly play a role in the huge differences in various FDI structural characteristics across individual transition countries: geography, size of the country, resource endowments, costs and skills of labour, government FDI policies and the investment climate in general. According to the latest World Bank Ease of Doing Business survey 2018 (published on 31 October 2017 and registering big shifts in ranking scores), EAEU and DCFTA countries received the following ranking (out of 190 countries surveyed): Georgia (9), Poland (27), Russia (35), Kazakhstan (36), Belarus (38), Slovakia (39), Moldova (44), Romania (45), Armenia (47), Hungary (48), Azerbaijan (57), Ukraine (76) and Kyrgyzstan (77). Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus and Georgia were among the top 10 countries which have managed to improve their ranking recently.

The bottom-line

In conclusion, the analysis from the forthcoming IIASA Fast Track FDI study implies that Eurasian Economic Union and DCFTA countries have not been particularly attractive for foreign investors; and if ‘round-trip’ inflows from offshore are excluded this issue is even more evident. This goes a long way to explaining why restructuring in the region has stalled. This pattern could change only with marked improvements in the domestic regulatory environments and investment climates. FDI inflows should also be promoted by pro-active government policies (at national and regional levels) which focus on attracting FDI in manufacturing and business services in order to assist restructuring and modernisation.

The article is a reprint of a IIASA blog post and was recently published in a longer version in the the wiiw Monthly Report No. 3/2018.

Photo credit: Earth Sciences and Image Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center (Link).