Kosovo’s problem with foreign direct investment

24 September 2018

Higher and better quality inflow would create jobs and enhance growth, but many challenges remain. The government needs a new policy mix to make it work.

by Pëllumb Çollaku

- Ten years after the global financial crisis, Kosovo’s appeal to foreign direct investors remains low.

- In order to increase the quantity and quality of foreign capital, Kosovo needs to overcome challenges such as political instability, corruption, and unreliable energy supply, a large informal economy and the poor rule of law.

- Improving the quality of the labour force, especially in skills upgrading in order to match applicants’ skills with employer needs, is a particular priority which should be tackled by the education system.

- The Kosovan authorities should also focus on the creation of a central governmental entity to be responsible for the coordination of FDI opportunities, building stronger judiciary, diligent commitments to the obligations stemming from the Stabilisation-Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU, and normalising relations with Serbia. This is a policy mix that would enhance Kosovo’s attractiveness to foreign director investors.

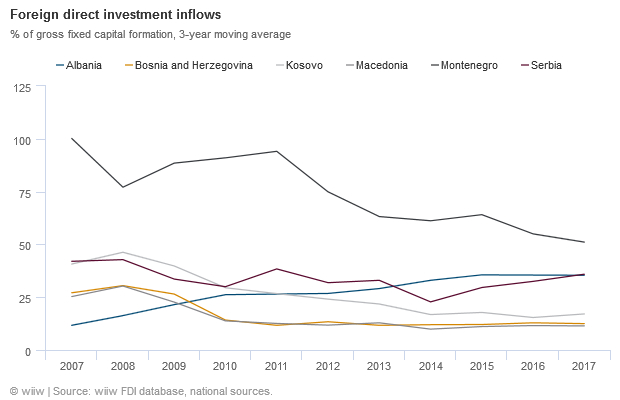

Kosovo was not an exception in experiencing a decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows following the global financial crisis. The only difference compared with most other countries in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE) was that decline did not hurt the country’s economy as much. This was mostly due to weak integration with financial networks and international trade. Ten years after the global financial system collapsed (which also coincides with the tenth anniversary of Kosovo’s independence), the country’s attractiveness to foreign director investors remains low.

The ‘successful’ FDI pre-crisis period of 2005-2008 was mostly driven by a sporadic process of privatisation. This process is still unfinished, largely due to political issues such as successive early elections due to the lack of legitimacy of the governments, border disputes with Montenegro and Serbia, and the long-running problem regarding the Association of Serb Municipalities. Disputes over the ownership of some assets have also proven difficult to resolve.

Since then, FDI inflows have fluctuated somewhat, but generally remained at a low level (see chart above). There are two possible explanations for this. First, that the country’s independence (and ensuing struggles for recognition), along with the global financial crisis, kept investors away. Second, a failure or absence of appropriate policies to attract foreign capital. In practice, it is hard to clearly isolate one or the other as the main explanation. However, based on regular studies commissioned by international institutions like the EU, EBRD, World Bank and IMF during the post-crisis period as the recovery in CESEE took hold, it is possible to outline the main impediments to FDI in Kosovo, and to list some issues to be tackled to increase the country’s attractiveness for foreign investors.

Advantages and challenges

There are several ways in which Kosovo is attractive to foreign investors. These include the country’s dynamic growth rate (with an average of 3.8% in last ten years), and its flat corporate tax rate at 10%. In addition, the ratified Law on Strategic Investment aims to ease market access for investors in key sectors. Meanwhile the launch of the Credit Guarantee Fund to improve access to credit together with the Law on Bankruptcy - an attempt to improve commercial legislation - are also key steps towards increasing Kosovo’s appeal.

In addition to these advantages, the ICT and extractive and metal processing industries have big potential, due to country’s richness in young human capital and natural resources such as ores, coal, lead and zinc. In addition, due to a low share of inward FDI in sectors such as food, infrastructure and energy, and a heavy reliance on imports for such products, there is a clear potential in these emerging sectors as well. Moreover, several international firms and franchises like KFC which are already present in the market, which is clearly a positive signal to foreign firms interested in entering the market. However, all these positive factors can not, and did not, compensate for the many challenges that the country has faced since its independence, and is still facing.

These challenges include limited regional and global economic integration, political instability, corruption (Kosovo ranks 85th out of 180 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, one of the lowest in CESEE), an unreliable energy supply, a large informal economy (estimated at 31% of GDP, mainly in the agriculture, construction and retail sectors), poor rule of law, and especially a lack of contract enforcement due to the weak judiciary. These factors all seem to have contributed to FDI decline and volatility over the last decade. This is part of the reason that Kosovo continues to rely on international financial support and remittances (representing over 15% of GDP in 2017).

Improving the quality of the labour force is the way to ‘catch up’

Kosovo has relatively a young population, with around 67% of its 1.8m people in working age (15-64). Along with Macedonia, it is the only country in CESEE with a higher activity rate now than in 2010, and the only one which recorded a population increase during the period 2010-2015 (a significant 8.2% rise, despite net outward migration). The official unemployment rate is 30.5%, while the youth unemployment rate hovers around (a horrendous) 52.7%. Mainly, this is because of the mismatch between applicants’ skills and employer needs (the education system does not link sufficiently its curricula to the needs of the business community). Therefore, improving the curricula in line with market needs is an imperative.

Focusing on training young people for new emerging service sectors relying on ICT and metal processing industries would be particularly beneficial. This would help both industries to attract new FDI, generating new jobs in the private sector, and improve the country’s low labour productivity. Kosovo’s labour productivity is the lowest in the region due to a high public sector share in employment (32.6%) and a small private sector.

Most importantly, a focus on skills upgrading would help to keep the young labour force at home. Increasingly, young people are migrating abroad, particularly recently due to the 'Westbalkanregelung', a scheme that gives priority access to parts of the German labour market to workers from six Western Balkan countries over those from other non-EU countries.

If Kosovo is able to improve the quality of its labour force, this could combine with low labour costs to attract significant new FDI into the productive sector. This in turn would spur exports, helping to close the country’s huge trade deficit (which is primarily a result of the very low production base).

Making it work

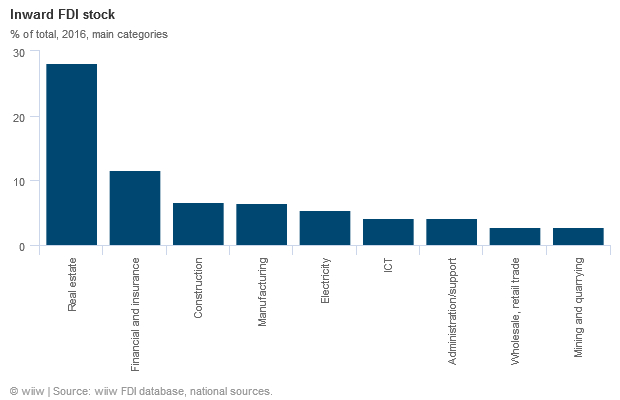

A major share of Kosovo’s FDI stock is in low value added activities like real estate and leasing (28%) followed by financial services (12%) and construction (7%) – see chart below. This clearly does not add much in improving country’s production base. Aside from upgrading labour quality, the Kosovan government should focus on the following four priorities.

First, there are many overlapping and time-inefficient procedures at the municipal and national level related to FDI. There is an urgent need to establish a central governmental entity which is responsible for the coordination of all FDI opportunities, especially big FDI projects.

Second, the nascent modern judicial system is a major obstacle to investment. As the US Investment Climate Statements 2018 puts it, in Kosovo the judiciary lacks the expertise to effectively handle complex economic issues. Furthermore, courts are perceived to be influenced by the executive branch, and enforcement is weak and time consuming. The recent resignation of the special prosecutor who was investigating pension fraud with war veterans only strengthens this impression.

Frequent government changes in the past due to a lack of legitimacy, and tensions with Serbia, have impeded the country’s regional and EU integration, as well as membership in relevant international organisations such as the OECD, WTO and UNCTAD. This has surely affected foreign capital inflows in the last five years. However, the current speeding-up of the normalisation talks between two countries sponsored by the EU looks like a light at the end of the tunnel. While there are several options discussed in public and on the table, the real plan may be to swap Serbian recognition of Kosovo for the autonomy of ethnic Serbs living in Kosovo, i.e. the Association of Serb Municipalities.

Finally, as the EU integration in substance is economic-institutional, completing homework deriving from the SAA and committing to the Multi-Annual Action Plan for a Regional Economic Area in the Western Balkans Six surely will increase Kosovo’s FDI attractiveness. In addition, commitments in building and connecting regional transport and energy infrastructure, as pledged under the so-called Berlin Process, would only enhance growth and promote healthy FDI and more jobs for the country.