Mental distress of refugees: a challenge for social and labour market integration

02 December 2019

About 30% of recent refugees in Austria show significant mental health problems. They need psycho-social support and psychotherapy, which would also facilitate integration.

photo: istock.com/Juanmonino

- Major stress factors for refugees after settling in Austria include discrimination, physical health problems, and the fear for partners or children living outside Austria and still waiting for a decision in the asylum procedure.

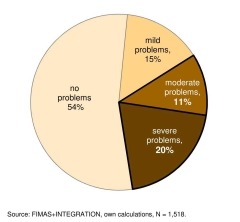

- A new wiiw study finds that 20% of recent refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq have severe mental health problems and, a further 11% have moderate problems. Younger refugees are particularly badly affected.

- Psychological strain can be lowered by learning German, family cohesion, the establishment of relationships of trust beyond the refugee’s ‘own community’, and access to adequate housing and employment.

- Psychosocial assistance and psychotherapy is essential to lower mental distress. Adequate public funding to guarantee sufficient and long-term provision of those services is necessary.

Mental health problems represent a major obstacle for many immigrants as they seek to get on in a new country. This applies equally to refugees in Austria, where such problems get in the way of their social and labour market integration. Low-threshold social support services and adequately funded psychotherapy are needed to support refugees with mental distress, as they make their way in Austrian society.

In the years following 2014, many people – especially from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan – fled the war zones and ended up in Austria. Refugees are particularly vulnerable to various risk factors for mental health problems. In their home countries, many will have experienced persecution and discrimination on various grounds, as well as physical and psychological violence. Economic and political insecurity are often accompanied by material hardship. In their travels or during their stay in refugee camps, they may have experienced life-threatening dangers and deprivation. In addition, separation from family members and being cut off from friends and support networks can result in psychological strain. Therefore, many refugees develop post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety or depression, or other mental health problems.

Once they arrive in a safe host country, life and limb are no longer threatened. However, mental health problems do not simply diminish of their own accord. New challenges can result in additional mental anguish: fear of deportation, physical health problems, separation from their family left behind, lack of proficiency in the host country’s language, limited possibilities to exercise personal autonomy, feelings of guilt and of loss, and restricted opportunities to meet and interact with others. All this can result in mental health problems either persisting or emerging. As well as health care and material support, refugees thus also need psychosocial assistance and adequate psychotherapy if they are to become active members of society in the host country.

Living conditions of refugees in Austria

In our study, we examine the prevalence of mental health problems among refugees who have arrived in Austria in recent years. Moreover, we analyse the relationship between stressors and relief factors and levels of psychological distress.

The study is based on data from the FIMAS+INTEGRATION refugee survey. More than 1,500 refugees aged 15–60 were interviewed between December 2017 and April 2018. Most had fled from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, and had already been granted asylum (or subsidiary protection). The questionnaire covered different areas of life, including: current labour market activity and experience in the country of origin; education and language skills; family situation; housing; social integration; and health. To measure psychological distress, the frequency of 10 different symptoms was assessed using a clinically validated scale (e.g. excessive nervousness, fatigue with no good reason, sense of hopelessness).

Prevalence of mental health problems

in the refugee population surveyed

The study shows that a significant proportion of those refugees interviewed in Austria were experiencing high levels of mental distress: 20% of respondents reported serious mental health problems and a further 11% moderate problems. A descriptive analysis of the survey data shows that younger refugees (aged 15–34) are particularly vulnerable, and women have higher levels of distress than men.

Adequate provision of psychotherapeutic care is required

Moderate mental health problems are associated with symptoms like occasional panic attacks, flat affect or circumlocutory speech. Moderate occupational or social conflicts are likely. In the case of severe mental health problems, serious symptoms like suicidal thoughts or severe obsessional rituals are likely, as is serious impairment in terms of social or occupational functioning (e.g. no friends, unable to keep a job).

Psychotherapy is the recognised treatment for both moderate and severe mental health problems. However, in the event of severe problems, medication is also likely to be necessary. Treatment is essential: mental distress increases the danger of doing harm not only to oneself, but also to others.

Stressors and relief factors: what hinders and what helps?

The study also examined the effects of stressors and relief factors on mental distress. Those people whose asylum applications were still pending were at significantly greater risk of mental health problems: the fear of being deported and uncertainty about the future resulted in permanently high levels of stress. Only after asylum was granted did the stress levels drop.

Obviously, physical health problems also increase psychological strain. Many refugees are in relatively poor health, as they come from countries where health care is in a bad way (not least due to war). Thus low-threshold facilities are needed in order to provide good access to health care for people with poor proficiency in German, lack of knowledge about the Austrian healthcare system and generally lower health awareness.

In addition, like all other migrants, refugees experience so-called acculturative stress on arrival: navigating their way in a new country with unknown social ‘rules’ creates insecurity. Thus, many waver between feelings of disorientation, hope and pressure to adapt. Experiences of rejection or discrimination significantly increase levels of mental distress.

Social cohesion is essential

In many respects, the study shows the relevance of close relationships of trust. Family cohesion is of great importance. Of course, this applies not only to refugees, but it is particularly true of persons whose partners or children have been left behind in the home country (or some other country during migration). The associated worries caused an elevated level of stress among those people interviewed. Those refugees who lived with other family members in the same household, displayed lower psychological strain. This underlines the importance of family reunification for the mental health of refugees. Relationships of trust beyond the immediate family are also important: respondents who said they knew someone to whom they could talk about personal problems were less stressed.

Good relationships in a broader social network and emotional well-being go hand in hand. The presence of more social contact outside a refugee’s ‘own community’ is significantly associated with lower mental distress. Thus, facilities that encourage social integration in the fields of education, training, leisure activities, etc. have positive effects that go far beyond the narrower purpose of assistance.

In particular, proficiency in the host country’s language enables people to interact more easily, helps to dispel fears and promote a more realistic perspective, and allows people to benefit from new opportunities. The better the German language skills of the refugees surveyed, the lower their level of mental stress. Steps should be taken to ensure that the public funding of language courses is adequate.

Access to housing and work helps

Satisfaction with housing conditions was found to be strongly associated with the mental well-being of refugees. Also access to work allows them to experience self-efficacy and, if the job is perceived to be meaningful, creates satisfaction. The relationship between mental stress and work is a reciprocal one: addressing mental health problems can facilitate finding a job, which in turn can lower psychological distress.

Conclusion: Time alone is not enough to heal the wounds – psychotherapy and steps to promote integration can speed the process

The study shows that mental distress is high among refugees, and that it does not simply disappear of its own accord once they arrive in the destination country. This has already been shown in the literature focusing on refugees from ex-Yugoslavia in various European countries. Only when steps towards integration – including gaining asylum status, receiving treatment for physical health problems, acquiring language competence, (re)establishing good personal relationships and social capital, and entering the labour market – are successfully taken, is the psychological strain experienced by refugees likely to diminish. To achieve those steps, many of the refugees who have arrived in Austria in recent years need psychosocial assistance and long-term psychotherapy. Appropriate treatment facilities do exist in Austria; however, it is necessary to ensure adequate long-term public funding of sufficient services to meet the demand.