wiiw Opinion Corner: Economic effects of Donbas trade blockade

01 June 2017

Looking at the recent developments in Donbas, wiiw Economist Vasily Astrov argues that the new status quo might result in a ‘lose-lose’ situation for both Russia and Ukraine.

In the latest wiiw Forecast Report (Spring 2017), I speculated whether the new geopolitical landscape – in particular the supposedly more business-like and Russia-friendly stance of the newly elected US President Donald Trump – may result in the United States partly losing its interest in Ukraine and, consequently, its leverage over the developments there. I argued that this may lead to a shift in Ukraine’s policies to the political ‘right’, with radical nationalistic forces likely to gain more ground at the expense of the ‘pragmatists’, a group including President Poroshenko, which may have potentially negative consequences for the situation in Donbas.

A trade ban within the country

During the recent months, this scenario has indeed partly materialised, albeit not necessarily completely for the reasons we expected: a real ‘rapprochement’ between Mr Trump and Mr Putin is yet to be seen. Instead, the developments in Ukraine have been driven by the logic of domestic politics rather than anything else. Starting from late January 2017, the veterans of the so-called ‘anti-terrorist operation’ (the official term for the military campaign against pro-Russian separatists), supported by several right-wing opposition parties, were blockading railway trade between Ukraine and the non-government controlled area (NGCA) of Donbas. Despite calling it (correctly) an act of sabotage which only hurts Ukraine’s economy, the Kyiv authorities were unable to remove the blockade which was widely popular, and ultimately legitimised and even expanded it (by imposing a ban on the movement of goods across the separation line by roads) on 15 March. In the official wording, the trade ban will stay in place until a full ceasefire is implemented and enterprises located on the territory of the NGCA are returned to their Ukrainian owners. (Large industrial assets were effectively nationalised by the self-proclaimed ‘people’s republics’ of Donetsk and Luhansk in response to the earlier unofficial trade blockade.) In another move, on 25 April Ukraine cut off electricity supplies to the ‘Luhansk People’s Republic’ (officially, because of the accumulated payment arrears), further adding to the disruptions of economic links between the NGCA and the rest of Ukraine.

Economic effects

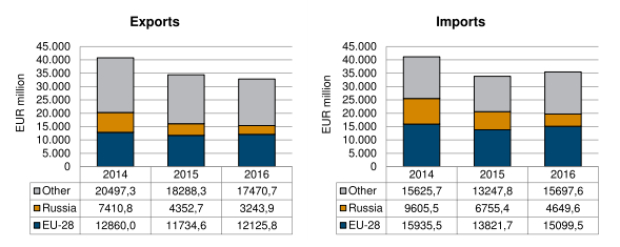

Clearly, the disruptions in cross-border trade will be costly for both sides at least in the short term. The stalled shipments of coal from the NGCA have already resulted in electricity shortages and have hit metals production in the rest of Ukraine. As a result, the country’s industrial production contracted by 4.6% in February and by 2.7% in March, after having surged by 5.6% in January (year-on-year). Although Ukraine started importing coal from elsewhere (such as South Africa and the United States), it is reportedly more expensive and of different quality, resulting in a higher import bill and some technical problems. At the same time, Ukraine’s exports of metals have suffered. All in all, the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) projects that the trade blockade will result in a current account deterioration by USD 1.8 billion this year and USD 1.1 billion in 2018, and in a lower GDP growth by 1.3 pp and 0.9 pp, respectively (see NBU report). For purely logistical, economic and social reasons, it would be more rational for Ukraine to trade with the NGCA (even if the latter is not under Ukraine’s direct control) rather than with countries in other corners of the world.(1) As Ukraine’s own recent experience with trade reorientation from Russia to the EU strongly suggests, such reorientation can prove very costly in the short run (see Figure 1), while long-run benefits are far from certain as well, unless it is accompanied by adequate investment inflows (see wiiw Working Paper No. 2016-12).

Figure 1 Ukraine’s foreign trade developments

In the so-called ‘people’s republics’ of Donetsk and Luhansk, there will be short-term losses as well, although less information is available on that. These losses, however, should be at least partly offset by the redirection of tax payments from the newly ‘nationalised’ industrial enterprises to the ‘people’s republics’ budgets, making them somewhat less dependent on Russian subsidies. Nevertheless, the reorientation of trade flows (mainly coal and steel) to or via Russia – though obviously enjoying Russia’s political support – may take time and certainly involve additional logistical costs.

A ‘lose-lose’ situation for Russia and Ukraine

More dangerous, however, is that the new status quo may be associated with much higher costs in the medium and long run, potentially resulting in a ‘lose-lose’ situation for both Russia and Ukraine. For Ukraine, disrupting the remaining economic links with the NGCA will not make the task of its economic reintegration any easier, while politically it is certainly counter-productive. Blackmailing the ‘people’s republics’ will hardly work, since they can turn to Russia for help instead (and have indeed already done so). Quite on the contrary, it provides them with another excellent pretext for anti-Ukrainian rhetoric. All in all, the trade ban makes the chances of any future reintegration (which is the cornerstone of the Minsk-II agreement) even lower, implying that the legal status of Donbas will most probably not be settled in the foreseeable future and military escalation will remain a risk factor. This, in turn, will negatively affect Ukraine’s investment climate for the years to come, diminishing its hopes for economic restructuring and modernisation and complicating the implementation of its Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU.

For Russia, in turn, the costs of supporting Donbas will only go up (Russia has, for instance, promptly made up for the electricity shortages in Luhansk following the cut-off from the Ukrainian side). The pro-Russian sentiment in Donbas will almost certainly strengthen further. However, Russia will hardly benefit from that, as long as it remains reluctant to formally incorporate Donbas into its own territory (as it has done with Crimea), even though it has recognised the documents issued by the self-proclaimed ‘people’s republics’. In these circumstances, it may prove difficult for the ‘people’s republics’ to attract even Russian investment, making the region a constant recipient of aid from the Russian government and a burden on the Russian budget.

In my view, the optimal solution for both Russia and Ukraine would be to recognise the reality, i.e. the apparent willingness of the people of Donbas to live with Russia rather than Ukraine (there is little doubt that any pro-Kyiv sentiment, to the extent that it still existed in Donbas, has largely evaporated by now). A legal settlement, however controversial, would be preferable to the current status quo and would ultimately have a positive impact on the investment climate and economic prospects of the region. I realise, however, that at the current stage this solution is a sheer utopia, as it would impose huge image costs on both sides. Acknowledging the formal independence of the NGCA would be political suicide for any Ukrainian president, while for Russia annexing the separatist areas of Donbas would certainly trigger another wave of international sanctions, ultimately burying its hopes (sincere, in my view) of any improved relations with the United States under President Trump. Without a legal settlement, however, the ‘lose-lose’ situation may well become a reality for both Ukraine and Russia for the years to come.

Footnotes

(1) For instance, neighbouring Moldova offers a relatively successful example of flourishing trade with its breakaway republic of Transnistria, which is de facto independent from Moldova, relies on Russia’s support and has its own currency. (Still, it needs to be added that the conflict in Transnistria has been frozen for more than two decades.)