Ten reflections on the UK in the aftermath of Brexit

10 October 2017

The UK’s decision to leave the EU provides a rare chance to see what happens when a generally stable, conservative country does something radical. It has brought into sharper focus some fascinating aspects of the country’s political culture.

A commentary by Richard Grieveson.

Photo: Nicolas Raymond, UK Grunge Flag, CC-BY 2.0

The Brexit process is overwhelming. The UK is currently producing way more news than it can consume. For those caught on the wrong side (EU27 citizens in the UK, and UK citizens in the EU27), the Brexit negotiations are nail biting. As political theatre, however, the whole process is fascinating.

The UK has had the bad luck to be landed with a particularly disastrous political class at a crucial moment in the country’s history. Complacency on the part of David Cameron launched the UK into a vote that it was not prepared for. Meanwhile Prime Minister Theresa May compounded the recklessness of Mr Cameron by interpreting what people had voted for in a very narrow and specific way, and launching the UK into a hard Brexit. In addition, she has appointed ministers such as Boris Johnson who do not even appear to be even taking it seriously.

This kind of radical departure from normal “stay-on-the-safe-side” political behaviour does not happen very often, especially in supposedly stable and conservative countries such as the UK. It therefore provides a rare opportunity to look inside the Westminster machine and the UK’s political culture more generally. The lessons from observing this are fascinating, and go way beyond Brexit. Some of them are also relevant for the EU27. Ten features of political life in the UK have become apparent since June 2016:

First, the UK is a highly divided country. The referendum and its aftermath have brought many conflicting views out into the open which effectively have nothing to do with the EU. These include very different attitudes towards immigration, regional splits, and a huge generational divide. One interesting way of categorising these splits is the “somewheres” and “anywheres” division proposed by David Goodhart.Mr Goodhart’s conclusions are centred on where people live, how educated they are, and their age, although he also leaves room for conservative or liberal values which people can hold irrespective of any of these other factors. The Brexit vote certainly supports this conclusion. 72% of people with no educational qualifications voted to leave the EU; only 35% of people with a university degree did the same. Young voters were strongly in favour of remain, while older voters favoured leave. Cities tended to vote for remain, while rural areas where more likely to support leave. (In this sense the UK is not unique. Recent votes including the US presidential elections, the Turkish referendum, Polish parliamentary election, and Austrian presidential election revealed splits along similar lines.)

Mr Goodhart is not right on everything (the recent general election result certain indicated some areas of weakness), but overall his distinction summarises the situation quite well; in both “somewhere” and “anywhere” land, there are things that you cannot say, or be known to even think. These sides do not talk to each other. Many “anywheres” in London are much more comfortable in the company of their equivalents in Paris or Brussels than they are with “somewheres” living just a few kilometres away in Kent or Essex.

Yet this isn’t the whole truth, as Mr Goodhart himself acknowledges. He thinks around 25% of the UK population are in between the two categories. One major point that he focuses on less is the generational divide, which is ever more visible and will increasingly become a political issue in the future. Rocketing property prices, which prevent young people buying a house or flat, and the distortions in the tax system (which mean poorer younger workers subsidise rich pensioners), are particular issues.

Second, mass immigration matters a lot to a great many people. This has become a huge issue in the UK, and was the single most important factor in driving the vote for Brexit.[1] In the 2013 British Social Attitudes survey, 56% of respondents said that immigration should be “reduced a lot”, and a total of 77% said it should be reduced. A recent YouGov survey found that well over half of British people agree with the view that “Britain has changed in recent times beyond recognition, it sometimes feels like a foreign country and this makes me feel uncomfortable”. Regaining control of immigration is the British public’s top priority in Brexit negotiations.

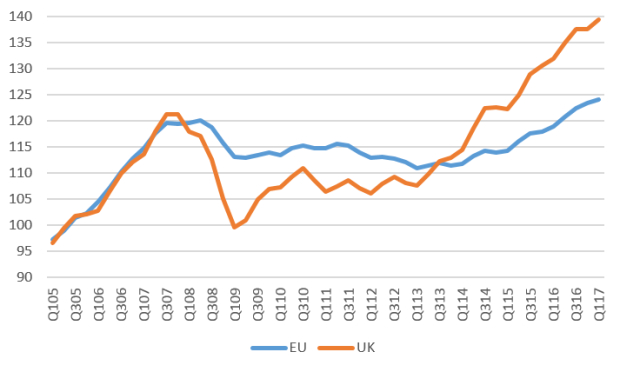

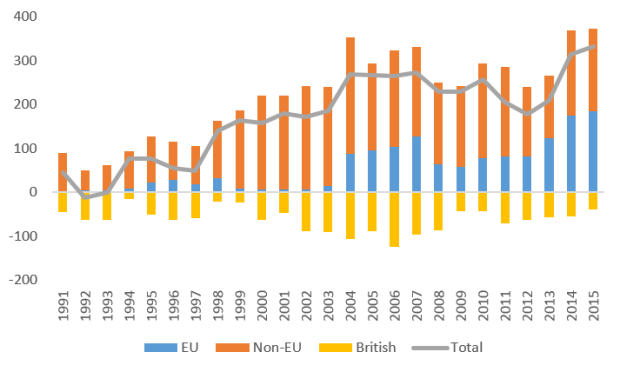

As Paul Collier, an economist from Oxford University and authority on global migration, has noted, immigration to the UK surged after 1997. Gross immigration averaged 305,000 per year in 1991-1997, and 542,000 in 1998-2015. Net immigration was 41,000 per year on average in 1991-1997, but this figure rose to 223,000 in 1998-2015. This is not, it must be said, primarily because of immigration from the EU. In every single year between 1991 and 2015 (latest available data), net immigration to the UK from outside the EU was higher than that from the EU. Surveys also appear to suggest that UK citizens have different views of different immigrants; those from the rest of the EU tend to be seen more favourably.

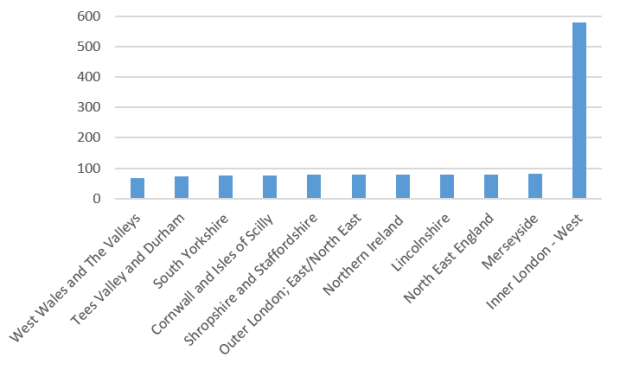

One issue is that arrivals have also been far from evenly spread across the country. Scotland accounts for 8.4% of the UK population and 32% of the land mass, but on average took only around 6% of gross immigration in 1991-2015. Over the same period, 46% of all gross immigration was to London and the South East of England, while only 3% went to the North East of England. The speed of change and uneven distribution appears to have been particularly important. One study after the Brexit vote showed that the rate of change in the foreign-born population, rather than absolute levels of immigration, was key in driving the vote for leave. At a time of cuts to local government spending, this has put acute pressure on public services in some areas. Mr Collier notes that by focusing on the impact on wages, many economists miss the real point: the main impact of mass immigration over a short space of time is felt in other ways.

Third, industrial decline since the 1970s has left some deep wounds. The structure of the UK labour market has changed materially since the 1970s, partly (but not only) as a result of policies introduced by the Margaret Thatcher government in the 1980s. Mr Goodhart shows persuasively how the “middle” has disappeared from the UK labour market over the last four decades, leaving a bulge at the top and the bottom. He argues that in the UK 25-40% of all jobs are now “low skill”, and that between 1996 and 2008, 55% of new jobs created were in this category. Manufacturing fell from 30% of GDP in the 1970s to 9% now, while formal apprenticeships dropped from 250,000 per year in early 1970s, to 50,000 by 1990. Like English Premier League football teams, many British employers have taken the option of importing skilled labour rather than using resources to train and develop staff domestically. Other big Western European countries have experienced some of these changes, but in places like France and (especially) Germany, the pace of change has been much slower.

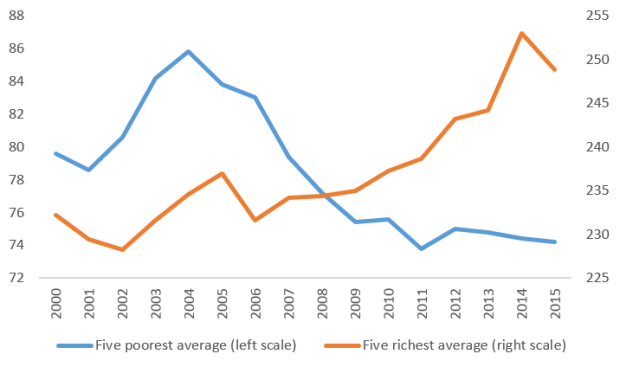

Mr Goodhart puts this mostly down to “Britain’s flexible labour market, privatisation, the contracting out of so many jobs by big companies, and the disappearance of a high wage floor in some sectors once sustained by unions and wage councils.” One consequence of all of this is that inequality has risen: the gap between rich and poor in the UK is much higher than for other big Western European EU members. (1) Wealth is highly concentrated in London, the South-East of England, and the main oil-producing area of Scotland; most regions in the UK are poorer than the EU average according to Eurostat data. Moreover, the gap between the poorest and wealthiest regions is growing strongly (see Figure 4 below). One of the reasons for the success of Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader, has been his determination to talk loudly and often about inequality.

Fourth, there is suddenly a greater awareness in London and the national media of what is happening in the regions, not just Scotland and Northern Ireland (which voted remain) but also Wales and the English regions (many of which voted to leave). In that sense, if Brexit really was a “cry for attention” from areas of the UK that have been socially and economically ravaged over the last few decades, it may have worked. Regions that were effectively abandoned in the 1980s have forced themselves back onto the political agenda. In this context, building further high-speed rail lines connecting regional capitals to London, while connections between many regional capitals remain slow and infrequent, will be even harder to justify.

Fifth, the UK political class has some startling weaknesses. The Brexit negotiations in Brussels have gone badly, and at times disastrously, so far. As Simon Kuper, a journalist and author, points out, the Brexit negotiations have demonstrated that the political class has is beset by weaknesses that are often visible more widely in the country: imprecision, an aversion to detail, a reliance on rhetoric and positive thinking, insularity, and delusions of grandeur which do last long once they come into contact with the outside world.

Sixth, the so-called “professionalisation” of politics in recent decades is a problem. One of the reasons that Mr Corbyn is so popular is because he comes across as being so straightforward and down to earth. He does not talk in the forced, overly-earnest, on-message way that almost all UK politicians do. (Theresa May is also not a “typical” slick Westminster politician in the style of David Cameron or Tony Blair; However, she often appears awkward in public and has been dubbed “the Maybot”.) Many politicians start out at Westminster as special advisors in their early 20s and rarely if ever leave. This is a problem partly because London is so different from most of the rest of the UK. Politicians end up talking in a different way to most voters, and often about the wrong topics.

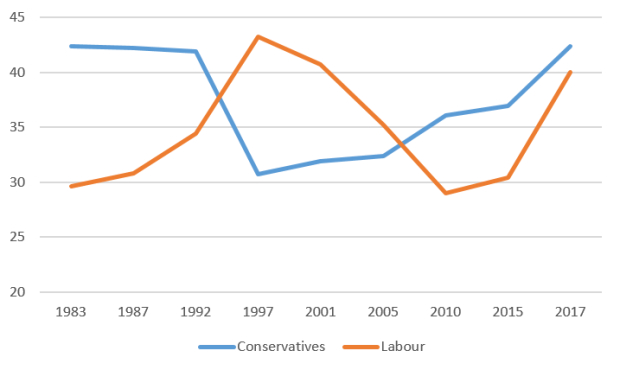

Seventh, the two-party system is still strong. In the 2017 general election, the Conservatives took their highest share of the vote since 1983, and Labour since 2001.(2) Both played to their base, moving away from the focus group-driven attempt to win centrist votes, and it appears to have worked. Interestingly, the Labour vote seems to be particularly sticky, and I doubt this is only because of the (undoubted) popularity of Mr Corbyn. Even if the old industries have mostly died, there are still many people who identify themselves as “working class”, and will never vote Conservative because of the memory of the 1980s. Meanwhile Labour is dominant among ethnic minorities, who are growing quickly as a share of the total population. Over the long run, it is highly unlikely that Labour will be able to navigate between its “somewhere” and “anywhere” voters (this is a challenge facing centre-left parties across Europe, as has been evident in the German and Austrian parliamentary campaigns), but for now it seems to be managing quite well.

Eighth, the internet has changed a lot about how campaigns are fought. Labour harnessed this very successfully during the most recent campaign, making extensive use of Facebook and Twitter to reach new voters and motivate existing ones. Stephen Bush, a journalist, also noted the importance of Labour having short, clear messages that played well to most voters’ brief attention spans when it comes to politics. Mr Bush argued that “most voters only think about politics for four minutes a week. Elections are won and lost in the news that people can’t escape – the beginning of the six o’clock or the ten o’clock news, before people switch off or switch over…The few minutes of news at the top of the hour on music radio.”

Ninth, referendums are no way to make such far-reaching and categorical decisions, at least not in the UK. Irrespective of whether you think Brexit is a good or bad idea, you have to be dismayed by the quality of the debate and the startling ignorance of the issues revealed since. It is clear that many people (on both sides) didn’t know what they were voting for and based their decision entirely on irrelevant factors. It is remarkable how even the most basic things about the EU—such as the difference between the Council, Commission and Parliament, or between the Single Market and Customs Union—were understood by only a small share of the population. Very few people in the UK understand what the EU is (the UK is probably not alone in this).

Real life is complicated, difficult and, ultimately for most people, apolitical. That is one of the main reasons why representative democracy is a good idea. People have a check on power, but they elect specialists to examine the issues for them. Winston Churchill famously said that the best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter. He was wrong, but only by one word; democracy makes sense, but referendums do not.

Tenth, UK soft power has taken quite a hit. The UK is one of the global leaders in soft power, thanks to factors such as its respected diplomatic service, the English language, London (which vies with New York for the role of unofficial global capital), several of its universities, pop music, the BBC (criminally underappreciated within the UK itself), the legal system, and Premier League football. This will remain the case, but it is clear that the last 16 months have changed outside perceptions of the country. If the UK backtracks on Brexit, it will be humiliating; if it purses this nonsensical path, it is likely to be even more so.

This is a shortened version of an article that first appeared in our September Monthly Report. For six months after publication, wiiw Monthly Reports are only available to members. To learn more about wiiw membership, click here.

(1) The UK Gini Coefficient in 2014 was 0.356 according to the OECD, compared with 0.297 for France and 0.289 for Germany.

(2) The Conservatives won 42.4% of the vote, and Labour 40.1%. Not since the 1970s had the two parties taken a combined share over 80%.