China’s Belt and Road Initiative: opportunity or threat?

05 September 2018

Launched five years ago, the initiative is still under heavy scrutiny over what it may bring to the EU, the EAEU and the countries in between.

By Amat Adarov

photo: last day in shanghai, Fredrick Rubensson, CC-BY-SA-2.0

- The idea of economic integration across the broad Eurasian space is facing challenges, as the dialogue between the EU and the EAEU has stagnated amid geopolitical tensions, while the New Silk Road initiative is raising concerns over the political and economic dependence of participating countries on China.

- Indeed, the commitment of China to the BRI is motivated by pragmatic considerations related to its internal and external policies. These include the need to revisit its economic growth model, develop lagging regions in its North and West, secure access to strategic resources, export markets and related infrastructure, and expand its economic and political influence in the region.

- Nevertheless, the BRI with its multiple proposed pillars extending beyond infrastructure development (including free trade, financial integration, people-to-people connections) appears to have the potential to transform the ever-challenging region between Europe and China.

- In this regard it is important to avoid confrontational ideology and focus on the areas of mutual interest (facilitating a non-discriminatory regulatory environment, the convergence of technical/SPS standards, greater cost efficiency and sustainability of investment projects), as well as avoid imposing ‘either-or’ choices on the countries along the New Silk Road.

- The long-run objective of facilitating peace and prosperity in the still problematic regions of Central Asia and the Middle East is in the common interest of China, the EAEU and the EU.

The China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is gaining momentum and is potentially capable of bridging Europe and Asia and transform the economies in-between with the massive investment it envisions. During a recent speech at a conference in Beijing marking the five-year anniversary of BRI on August 27th, Chinese President Xi Jinping reiterated his country’s commitment to the initiative and reviewed its progress to date. He also defended the BRI against complaints that the endeavour will leave participating countries with unsustainable debt burdens, after Malaysia recently halted its two major BRI-linked projects worth over $22 billion, fearing a debt trap.

At the same time, recent years have been marked by major challenges to the idea of integration across the broad Eurasian economic space. Cooperation between the EU and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) has stagnated amid geopolitical tensions, while both blocs are also facing internal difficulties: rising populism and anti-integration sentiment in the EU, macroeconomic challenges in the EAEU. The BRI, while bolstered by China’s political enthusiasm and strong financial underpinnings, still remains a rather vaguely defined endeavour and complementarities with the two other major players in the region—the EU and its Neighbourhood Policy and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU)—are not clear, warranting further discussion of prospects and challenges concerning cooperation across the Eurasian space.

The Belt and Road Initiative in brief

The idea of establishing a broad-based cooperation across the Eurasian region to promote the New Silk Road was raised by Chinese President Xi Jinping during a series of foreign visits in 2013 and the term ‘One Belt, One Road’ was introduced at a conference in Shanghai in May 2014. The official document ‘Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ further outlining its content was released in March 2015.

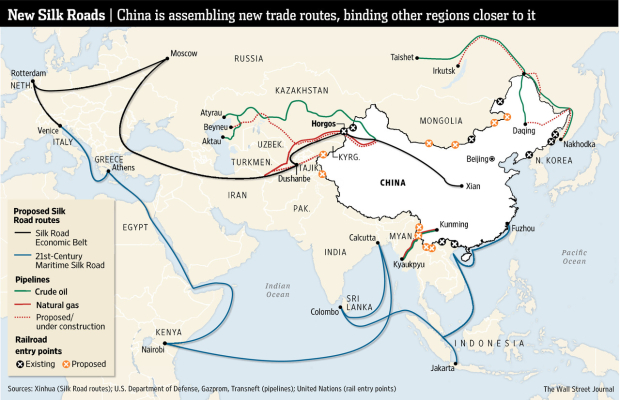

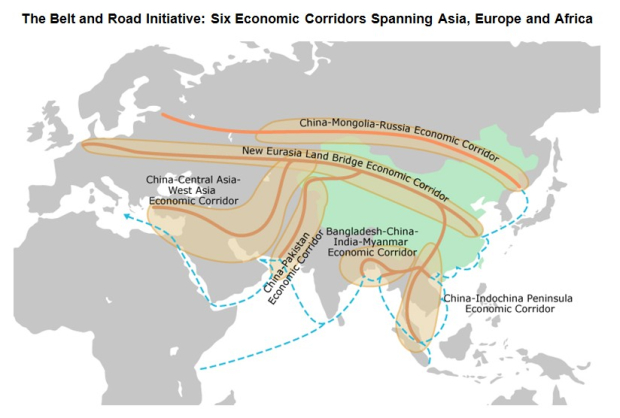

The main objective is to facilitate economic connectivity between Asia and Europe along the route largely resembling the ancient Silk Road—hence the name—via two major components: the Silk Road Economic Belt (land-based component) and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (sea-based component). The Silk Road Economic Belt will connect China to Europe via land transport corridors extending throughout Central Asia, the Middle East and Russia, while the Maritime Road will link the South China Sea and the Mediterranean Sea via the Strait of Malacca, the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal. In addition, six envisioned economic corridors will bridge the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Road, including (1) China-Indochina Peninsula; (2) Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar; (3) China-Pakistan; (4) New Eurasian Land Bridge; (5) China-Central Asia-West Asia; and (6) China-Mongolia-Russia (see Figure 1).

The BRI currently covers 65 countries in West, Central, East, and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and Central, Eastern and South-eastern Europe, and will potentially eventually expand to include over 100. According to official documents, the strategic goals of BRI include several pillars: policy coordination, connectivity of infrastructure, free trade, financial integration, and stronger people-to-people connections. The ultimate aim is to improve cross-country transport and communication infrastructure, facilitate cooperation in trade and investment, tourism, and financial markets, and strengthen cultural ties between participating nations in a flexible and mutually beneficial way. The development of cross-border infrastructure is apparently the key economic element and is largely a prerequisite to effective further cooperation and connectivity improvements. Altogether this makes the endeavour truly ambitious in terms of both scope and scale.

Figure 1 / New Silk Road

Note: the top panel shows the New Silk Road land-based and sea-based components; the bottom panel shows the six economic corridors.

Prospects and challenges of the initiative

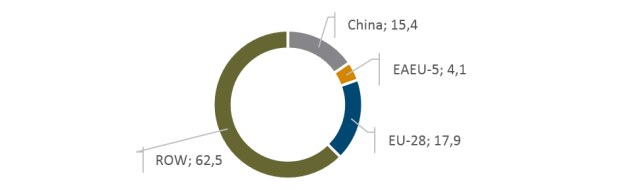

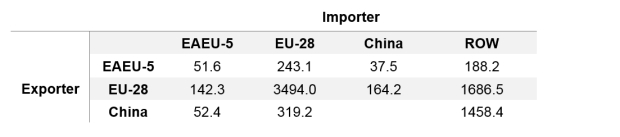

Bridging the economies of Europe and Asia in general and the three ‘integrations’, the EU, the EAEU and China, in particular is a highly welcome idea: the sheer economic size of such integration is impressive as jointly the EU, the EAEU and China account for almost 40% of the world aggregate GDP (Figure 2). Including the countries in-between, an estimated 60% of global GDP and up to a third of the world’s population potentially is to be covered by BRI.

It is therefore not surprising that ideas to improve connectivity of the economies and expand along the way China’s regional influence are not new, and a number of earlier initiatives by China had similar objectives (for instance, the ‘Go Global’/‘Go Out’ and ‘Peaceful Rise’ policies). To a certain extent, the BRI is a repackaging and reformulation of the ‘Go Global’ strategy that was in place before—a policy mostly focusing on investments in various projects abroad, predominantly in infrastructure. This time, however, the initiative appears to have gained a much stronger impulse with a better-shaped conceptual framework and significant dedicated funding. In particular, the endeavour is backed by financial infrastructure involving multiple sources: the Silk Road Fund (US$ 40bn), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (US$ 50bn), the New Development Bank of BRICS (US$ 10bn), the Silk Road Gold Fund (US$ 15bn), and the China, Central and Eastern Europe Investment Co-Operation Fund (US$ 11bn). In addition, the project is supported by bilateral funds (China-Russia, China-India, China-Africa developments funds) and specialised Chinese organisations (for instance, the China Export-Import Bank and China Development Bank), as well as complementary initiatives by the World Bank, EBRD and other international development organisations operating in the region. While the committed funding seems massive, the foreseen investment needs along the lines of BRI are very high as well, albeit the scale is not clear with estimates ranging from US$ 1-8trn, and it is not currently apparent that even the level of US$ 1trn will be met by available funding.

The commitment of China to the BRI is motivated by pragmatic considerations related to both its internal and external policies. The following goals appear to be strongly complementary to the project:

- The need to revisit its economic growth and development model. China’s economy has been growing at an accelerated pace for years driven by exports of labour-intensive goods. Nowadays, as the country’s income levels have increased and it is facing a structural economic growth slowdown and a ‘middle-income trap’, previous sources of growth need to make way for new drivers. Policymakers in China recognise the need to transition to a more sustainable economic growth and development model, based on a greater role for domestic consumption and shifting up global value chains, as well as the need to utilise the excess capacity China has accumulated over years.

- Development of lagging regions of China. Closely related to the above is China’s need to facilitate the development of its less developed Western regions, reduce income inequality and thereby improve the internal cohesion of the country.

- Secure access to strategic resources. The economy of China is highly dependent on access to energy resources, metals and other natural resources. The New Silk Road will provide new and alternative routes to secure access to mineral resources from the commodity-based economies of Central Asia and the Middle East.

- Expansion to new markets and promotion of the Yuan. The BRI will help China gain improved access to new markets for goods and services, as well as facilitate investments to help optimise the composition of its value chains in light of its new development paradigm. Deepening trade and investment linkages will help further strengthen the role of the Yuan in the region and beyond.

- Geostrategic interests. The BRI is fully consistent with the overall strategic goal of China to increase its regional and global influence along multiple dimensions, including economic, political, people-to-people linkages, and to create a ‘circle of friends’ in the rather problematic neighbouring regions of Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa.

Figure 2 / GDP (PPP-based), share of the world total, 2007-2016 average

Table 1 / Trade among the EU, the EAEU and China, US$ bn, 2007-2016 average

As noted above, the BRI is a rather vague integration ‘vision’ and thus lacks a well-defined multilateral framework in terms of overarching regulatory arrangements and governance, instead relying on flexible bilateral agreements. The latter has both pros and cons. Such format allows for the identification on a case-by-case basis of mutually beneficial forms of cooperation. In fact, the Chinese government has emphasised that all countries are welcome to participate in the BRI, and that the sovereignty and will of the partner countries will be respected. Participation thus is at least formally not constrained by specific pre-arranged legal frameworks and conditionality, which could turn away some potential partners. At the same time, such flexibility increases uncertainty and makes it more difficult to anchor expectations and commitments of potential partners, inhibiting long-run business planning as cross-border connectivity projects require joint cooperation of all countries along the route in order to be fully functional.

Related to the above, the region along the BRI route is highly challenging along multiple dimension. The envisioned Silk Road Economic Belt passes through a range of landlocked countries located in highly mountainous or desert terrain, which makes it especially costly to develop infrastructure. Moreover, parts of the region are beset by geopolitical tensions and open conflicts, and many of the countries are fragile states with recurring social unrest, and weak institutions aggravated by macroeconomic challenges. This altogether presents additional challenges and risks for the future of the BRI. Looking beyond mere infrastructure connectivity, the BRI will pass through multiple borders with countries having rather different regulatory regimes and capacity to effectively implement cross-border control operations, which may jeopardise the speedy transit of goods.

BRI: competitor or partner to the EU and the EAEU?

In light of the flexibility of the BRI, the extent to which it is complementary to the EU and the EAEU depends largely on the actual negotiated depth and parameters of cooperation with the EU, the EAEU and the countries along the BRI route. At the moment, in light of the stalled dialogue between the EU and the EAEU, the New Silk Road initiative appears to be a well-positioned platform to promote integration on the broad Eurasian economic space at least in the cross-border infrastructure developments domain. For the countries between Asia and Europe the BRI surely represents a remarkable opportunity to accelerate their growth and development. At the same time, this may come at the risk of higher long-run dependency on China, particularly for less developed countries of Central Asia and Middle East, in the form of China’s control over the logistics networks, ownership of infrastructure in the host countries via direct investment, and potential debt sustainability issues on account of immense financial assistance from China. However, increasing integration inevitably comes at the cost of greater interdependence and related spill-over risks, and for the small economies of the region lacking other development opportunities this may be the only feasible option.

The influence that China will gain throughout the region is often seen as a competition to the similar aspirations of the EU and the EAEU. In particular, the BRI is often seen in the EU as a largely geopolitically-motivated initiative, with unclear political intentions from the Chinese side. The fact that since 2014 a range of countries in Central, Eastern and South-eastern Europe, including EU members, signed Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) with China and a ‘16+1’ format was established to further deepen cooperation, is seen with caution by the EU leadership as potentially jeopardising cohesion within the EU.[1] The engagement of the EU in the EU Neighbourhood and beyond in the form of technical and financial assistance has been less flexible as the countries willing to pursue deeper forms of integration with the EU must approximate to the EU regulations (acquis) and accept ‘European values’. While this certainly helps generate incentives to transition to democracy and a market economy, it is also limiting. Not every country in the region would be willing to embark on large-scale institutional reforms and liberalisation in light of the costs of reforms involved, established political and institutional systems or differing cultural values, which is particularly the case for many countries of Central Asia and the Middle East.

As regards cooperation perspectives of the EAEU, while membership in the EAEU itself indeed puts binding constraints on its members’ foreign trade policy (adoption of the common external tariff and technical/SPS standards of the bloc, delegation of certain competencies to the supranational level), the bloc is generally open to partnership in other formats not requiring membership in the bloc, ranging from free trade agreements (already signed with Vietnam and Iran) to cooperation limited to certain sectors and policy areas. On account of macroeconomic difficulties, the bloc nowadays has rather limited capacity to extensively engage in the New Silk Road initiative, and has yet to deal with internal challenges related to remaining barriers to flow of goods and services, capital and labour.

While difficulties exist, simultaneously pursuing partnership with both the EU and the EAEU is nevertheless possible: a case in point is Armenia, which is a member of the EAEU since 2015 and also signed a Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement with the EU in 2017. Deeper forms of economic integration are however constrained by the differences in regulatory regimes, in particular, differences in technical and SPS standards between the EU, the EAEU and China. In general, Chinese and EAEU standards are lower, while the EU standards are higher and may in fact be too high for producers in less developed economies.

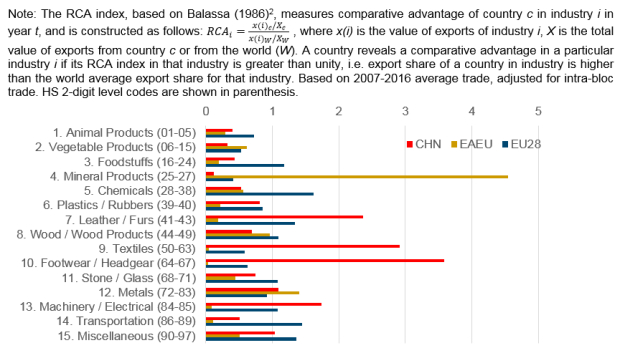

Improving transport connectivity and possibly reducing regulatory barriers to trade along the way will increase the competition between the EU, the EAEU and China’s producers. The economy of China is highly competitive across many sectors, including high value-added industries (see Figure 3) and connectivity gains will increase competitive pressures on producers in the EU and especially the EAEU, which is largely competitive in petroleum and metal sectors. This is further aggravated by concerns, especially voiced in the EU, that China’s enterprises participating in BRI will enjoy ample financial and administrative support from Chinese authorities and state-owned banks. In this regard it is important to facilitate regulatory transparency and level-playing field to ensure fair competition, which is an important prerequisite for future broader and deeper cooperation in the context of pan-European-Eurasian economic integration.

Figure 3 / Export competitiveness of industries, EU, EAEU, China

Despite challenges between the three integration initiatives (EU, EAEU and China-led New Silk Road), ‘integration of integrations’ is both highly desirable and feasible, provided that there is political will for it. While the EU can become the western, the EAEU can become the northern ‘pillar’ of the BRI. Development of cross-border infrastructure is complementary to the internal economic development objectives for all three integration initiatives. More specifically, in the case of the EU it may help to boost the development of the European ‘periphery’, particularly, the lagging regions of the Western Balkans and EU Neighbourhood countries. For the EAEU the less developed members—Armenia and Kyrgyzstan—as well as the vast lagging Siberian regions of Russia may benefit from the BRI, receiving a growth impulse, similarly to the Northern and the Western regions of China. There is scope for cooperation in various areas, including trade and investment facilitation, environmentally sustainable economic development, and science and technology collaboration.

In this regard it is particularly important to steer joint efforts to ensure that cooperation on the pan-European-Eurasian space results in a competitive and non-discriminatory trade and investment regulatory environment, facilitates convergence of technical and SPS regulations and related conformity assessment procedures, coordinate efforts on infrastructure building to achieve greater cost efficiency, and prevent possible unnecessary duplication of projects and construction of projects that are not sustainable. Above all, it is important to side-step confrontational ideology and focus on areas of mutual interest in the region, as well as avoid imposing ‘either-or’ choices on the countries along the New Silk Road as regards to which integration vector they choose to pursue. In the end, the long-run objective of facilitating peace and prosperity in the still problematic regions of Central Asia and Middle East is in the common interest of China, the EAEU and the EU.

Footnotes

[1] For a list of MoU in place as of 2018 see Steer Davies Gleave, 2018, Research for TRAN Committee: The new Silk Route – opportunities and challenges for EU transport, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, January 2018.

[2] Balassa, B. (1986). Comparative advantage in manufactured goods: a reappraisal. The Review of Economics and Statistics 68(2): 315-19.