Nationalism and democracy in the Balkans

02 May 2017

Many factors point to a rising risk of nationalism and authoritarianism in the Balkans. However, the reality is somewhat different. A commentary by Vladimir Gligorov.

Summary

- Ethnic diversity, frozen conflicts, weak institutions and anti-foreigner sentiments all point to the likelihood of rising nationalism and authoritarianism in the Balkans.

- However, the reality is somewhat different. Ethnic diversity creates competition, which acts as a check on any one group gaining too much power. Political competition within particular ethnic groups is prevalent across the region, and has the same impact.

- Economic nationalism is more of an issue, de facto created by frozen conflicts in the region. This has had negative economic ramifications, including keeping employment levels very low.

- However, most states have found a partial way out of this trap via external trade. Exports/GDP ratios have risen almost everywhere in the past decade. This should continue to drive employment growth, thereby contributing to broader stability in the region.

Now that nationalism is fashionable worldwide, democracy is deemed “archaic”, and European Union member states are contemplating Balkanisation, what is the state of nationalism and democracy in the Balkans?

To answer, one needs to look at prospects for authoritarianism and economic protectionism. Their chances should be on the rise because of persistent political instability and lack of economic development. And then there is ethnic diversity and multiculturalism. Even more important are frozen conflicts in practically all the countries. In addition, there is the low standing of representative institutions, in particular of the parliaments. Finally, foreigners are not trusted, foreign investors as much as politicians or military. Foreigners are viewed by many as stealing jobs, pressuring governments into bad deals, and corrupting local elites and the establishment. So, why not support strong leaders and protect national interests, political and economic? Democracy is just a way to betray these interests through internal divisions.

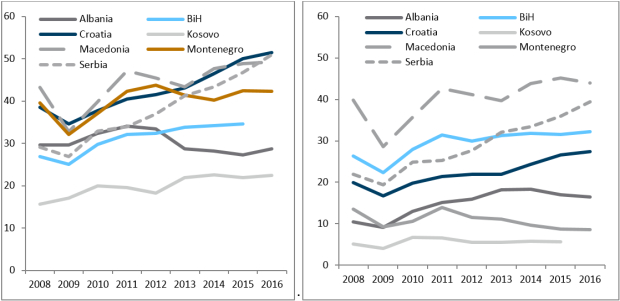

So, why not go authoritarian and protectionist? Put differently, what are democracy and free trade good for? Indeed, though all the Balkans democracies are deficient in one way or another, outright authoritarian systems are not to be found (I put Turkey aside). Also, though Balkan economies tend to be more closed than other European economies of similar sizes, in terms of trade regimes, these are open economies (Figures 1 and 2). They all have free trade agreements with the EU, most of them are members of the WTO, and countries that are not members of the EU participate in the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), the regional free trade area. In addition, openness (exports to GDP) has been on the rise, especially since 2008-2009 (Figures 1 and 2).

Intra-ethnic competition is a crucial check on authoritarianism and nationalism

Moreover, most recent political instabilities and turmoil have tended to be resolved, to the extent that those were resolved, by democratic means. One reason is that in most cases intra-ethnic political competition has persisted. Even in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Western democracies in their wisdom (“Balkans are different”) installed an ethnically based undemocratic constitution (within the Dayton-Paris international agreement), there is some intra-ethnic political competition, which at least prevents the erection of proper authoritarian rule (though not in the informal sense).

Similarly, in Montenegro, authoritarianism has been a real possibility mostly because intra-ethnic competition has been limited. This is changing slowly because democratic institutions, e.g. regular elections, have not been suspended. There democracy can be sustained or improved in two ways. One is for political competition within the ethnic groups, primarily Montenegrins and Serbs, to increase, and that primarily refers to the latter group. Another is for political competition to cross over ethnic divisions, which becomes feasible once the frozen conflict over the independence of the state is resolved.

There is then the case of Macedonia where it is precisely the existence of the intra-ethnic political competition which is stabilising democracy and the state. Given quite adverse regional and international circumstances, this is almost remarkable. The prolonged slide into some kind of shared authoritarianism (shared by a coalition of a Macedonian and an Albanian party) has been resisted and was denied a mandate in the last December’s early elections. Post-election politics has been characterised by an attempt to confront nationalism with democracy, but with no viable authoritarian alternative, there is only a democratic exit from the current impasse in the institutions and in the streets. The key to the survival of democracy is political competition within the majority Macedonian population.

And that leads to the issue of the Albanian politics, which has regional ramifications – similar to the politics of Serbia to which I will come next. The key characteristic of Albanian politics in Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia (and even in their communities in Montenegro and Serbia) is the shallow legitimacy of their governments. There is consequential political competition for representation and tenuous legitimacy, more often than not denied in elections or in the streets, which keeps the democratic process alive. From time to time there is an attempt by one embattled leader or another to mobilise pan-Albanian nationalism, but that has not provided the needed legitimisation for those leaders so far. With intra-Albanian political competition, democracy supports stability.

The case of ethnic Serbian leaders in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro is similar. Indeed, it is only in Montenegro where there is little intra-Serbian political competition, and it is only in Bosnia and Herzegovina where an authoritarian, but contested, government has been installed. And it is only in Serbia where there is a push for a Presidential system which would support increased authoritarianism. However, within the Serbian population there is strong political competition which keeps the democratic potential alive and denies Serbian leaders access to nationalist authoritarianism.

Thus, intra-ethnic political competition stands in the way of authoritarianism and keeps democracy alive in the Balkans - even though the region is more connected by frozen conflicts than by political or any other values.

Economic nationalism being overcome by expansion of external trade

Now, why not economic nationalism, which is to say protectionism? For one thing, frozen conflicts provide for a level of non-tariff and non-trade barriers, which are damaging enough. The distorting effects of these protectionist practices are felt most of all in the region’s labour markets. The region employs too few people and has very high unemployment and outward migration rates, more often found in conflict zones or on territories with frozen conflicts. In that respect, the so-called Western Balkans region is one large frozen conflict made up of a number of inter – and intra-state frozen conflicts.

With that in mind, and especially after the financial drought brought about by the crisis of 2008-2009, practically the only policy which could preserve and indeed increase demand for the region’s production has been external trade. Trade is a demand managing policy which can have quite strong effects on small economies. Table 1 summarises the growth of exports and of GDP in the Western Balkans.

With the exception of Albania, which has been hit by the decline in oil prices, all countries in the region have seen faster or much faster growth of exports than of GDP. Indeed, for the most part, a recession or its persistence has been averted with the increase of exports. Importantly, exports to the EU have increased faster than to the rest of the region, i.e. to CEFTA. In addition, with the exception of Serbia and Albania, all the other countries either use the euro or have fixed exchange rate regimes based on the euro.

Dangers of nationalism and authoritarianism are greater elsewhere

Thus, in summary, intra-ethnic political competition and growing exports have been supportive of democracy and free trade and have kept in check nationalism and protectionism respectively. Thus, the Balkans has yet to balkanise again, and one hopes it will not, while the EU member states, USA, and Russia are going nationalistic and are getting tired of democracy and free trade. Hopefully, the EU member states are going to shrug of the temptation.

Photo: Vanco Dzambaski, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0