New Kosovan government faces a daunting set of challenges

18 January 2018

Political issues may take up much of the agenda, but the administration will need to address the trade deficit, deficiencies in education and weak labour productivity.

By Pëllumb Çollaku.

- The new government, formed in September, is made up of 12 parties and has a tiny majority, which could lead to political instability.

- It will face the same big political challenges as its predecessor, namely border demarcation with Montenegro and the status of Serbs living in Kosovo. The new prime minister has made big promises on visa liberalisation and the establishment of an army, but both face significant obstacles.

- The chances of political instability have risen further recently, owing to the desire by prime minister’s party to withdraw from an international court investigating war crimes, and the assassination of a leading ethnic Serb politician in the north of the country.

- The economic challenges facing Kosovo remain huge. In particular, the government will need to address the trade deficit, deficiencies in the education system, weak labour productivity and ensuring an adequate and stable energy supply.

An early parliamentary election took place in Kosovo in June 2017, and the country has had a new government since September. The early election was triggered by a motion of no confidence in the government of Prime Minister Isa Mustafa a month earlier. The formation of the new government came after three months of waiting, and was agreed only after the AKR party accepted PAN’s pre-election coalition (PDK, AAK, NISMA and eight other small parties) offer. Ramush Haradinaj (leader of the AAK party) has been elected Kosovo’s prime minister.

The new government has a wafer-thin majority of only 61 out of 120 MPs in parliament. This could lead to political instability, particularly given the large number of parties (12), most of them small, which form the government. The AKR alone took five ministries, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the position of first deputy prime minister, despite only having four MPs. In addition, the constitution grants ten seats to Kosovo Serbs and other minorities, further adding to political fragmentation. Mr Haradinaj has made big promises, including on visa liberalisation and the establishment of a Kosovan army, although progress on both will be challenging.

The broad coalition is a result of the difficult bargaining after the election, and its size is likely to put a strain on Kosovo’s budget. This is because in order to fulfil the requests of all the parties in coalition, it was necessary to also restructure the institutions within the central government, including the establishment of new ministries (2), a high number of appointed deputy prime ministers (5), and a huge number of deputy ministers (70). These changes in the organisation of the government have not been perceived positively by the general public. This has also lowered public expectations regarding what the government can achieve.

There have already been signs that the public is unhappy with the new government. This was reflected in the local elections that took place in October 2017, and the rise of the left-wing party Vetëvendosje! (VV), which had already done well in the general election, was also confirmed at the local level. At the last local elections in 2013 VV won only one municipality, the capital Prishtina. This time they reached runoffs in six municipalities, winning three - Prishtina, Prizren (the second largest city), and Kamenica (although the party now looks to be facing major problems of its own).

New administration faces same big challenges as its predecessor

In the near term, the new government will have to deal with two major issues that the previous administration failed to deliver on, specifically i) the border demarcation with Montenegro, and ii) the creation of the Community of Serb Municipalities (CSM). In addition, there is a need for the prompt resumption of the EU-facilitated dialogue on normalising relations with Serbia.

The border demarcation with Montenegro remains a hot topic, and the prime minister appointed a new commission in order to come up with recommendations. On December 4th the commission rejected the demarcation line findings of its predecessor (which had been dismissed), and argued that they should be not taken into consideration by the parliament for approval. Even before they were presented to the government, these new findings were opposed by, among others, the US Embassy in Pristina, which emphasised that such assertions are 'unsubstantiated, misleading, and wrong'. There is little hope that the situation will improve soon; the prime minister recently stated that if the new commission comes to different findings, Kosovo will seek a solution through arbitration. If that happens, it is likely to have negative implications for Kosovo, both in terms of further delays to visa liberalisation, and economic growth.

The process for the creation of the CSM has received a further blow. An agreement was signed in Brussels in 2013 by Serbia and Kosovo to establish a self-governing association of municipalities with majority Serb populations in Kosovo. However, mass opposition protests led to the failure of the ratification in the parliament. In 2015, the EU brokered an agreement to create a new Association of Serb Municipalities (ASM) in majority-Serb areas in Kosovo. However, a further setback emerged after the Kosovan government passed a law on postponing the privatisation of the Trepça mine in 2016 (after the pressure of the opposition parties). This resulted in Serb MPs boycotting parliament.

Under the new government, there is a chance of renewed positive momentum on the CSM. However, whether or not the new government will deliver is still questionable, because of the tensions it might provoke (the idea remains highly unpopular in Kosovo). Along with the CSM, the new government has promised to also put forward a new agenda to transform the current mandate of the Kosovo Security Forces (which currently only serves for emergency situations) into a regular army. As both issues require a change in the constitution, and the KAF is opposed by Serb MPs and Belgrade government, while the CSM by many in Kosovo, one muted compromise solution is to pass the legislation for both measures together.

The potential for compromise has been reduced, however, after Mr Haradinaj’s AAK party tried to overturn a 2015 law ensuring Kosovo’s cooperation with the Kosovo Relocated Specialist Judicial Institution (KRSJI) in December. This move was heavily criticised by the international community, especially by the US Government. According to several foreign ambassadors in Kosovo, such an initiative would be the worst development in Kosovo’s post-independence history, and could further isolate the country. The KRSJI was set up after a Swiss senator in the Council of Europe alleged in 2010 that the KLA had been engaged in organ trafficking during the Kosovan War.

The murder of Oliver Ivanovic, an ethnic Serb politician in Kosovo on January 16th, could have significant implications for talks between Serbia and Kosovo. Mr Ivanovic was president of the civic initiative Freedom, Democracy, Justice (SDP). Following the shooting, the Serbian delegation involved in talks with Kosovo in Brussels announced that it was leaving and returning to Belgrade.

Lack of clarity on how economic agenda will be pursued

While the government is likely to be busy with these political issues, the economic challenges facing Kosovo are no less important. Under the new administration, changes in the structure of the central government have been made in attempt to increase economic development. Two additional ministries have been established: the Ministry of Regional Development, and Ministry of Innovation and Entrepreneurship). The Ministry of Innovation and Entrepreneurship’s core mission will be to increase productivity and growth by improving the operating environment for SMEs (for example boosting innovation programmes), while the Ministry of Regional Development will focus on designing regional policies to ensure economic development across the whole country. Responsibility for strategic investments have been assigned to the Ministry of Diaspora, in an attempt to exploit the potential for Kosovans living abroad to increase foreign direct investment inflows.

With so many industries and five parties competing to push forward their priorities, there is a risk of a lack of coordination of policy. Kosovo now has 21 ministries, the highest number in its post-war history. While the fact that six of these ministries will be responsible on pushing the government’s economic agenda indicates a strong focus on this area, it remains unclear how such a decentralisation of economic policymaking will function in practice. Some newly appointed ministers have announced their objectives publicly, but the government has not published specific mandates and targets for the new ministries.

Central role for fiscal reform

However the government functions, a key part of achieving progress on economic reform will be determined by its fiscal policy. Significant fiscal reforms, labelled “Fiscal Package 1”, were initiated by the previous government in September 2016. This package included tax stimuli, which increased the value-added tax (VAT) threshold from 16% to 18% for goods and service, while lowering VAT to 8% for some goods among others grains, pharmaceuticals, and IT equipment. In addition, the customs tax on new machinery used in production processes was also abolished. Such policies look promising in terms of improving economic activity in the medium term, although at the present time there is neither data nor a study analysing the effects of this reform. Table 1 on imports in new machinery shows a slight increase from 2015 to 2016, possibly due to such applied measures. Even though the new measures were only in force for the last four months of 2016, early indications are positive.

The new government looks set to continue where its predecessor left off. In July, the previous government put forward “Fiscal Package 2.0”, which included measures to support the private sector, such as abolishing the customs tax on raw materials used in the production process. The new government passed the new fiscal package into law in October 2017. It is expected to produce positive results, namely increased domestic supply, in the medium term. Although still early, the experience of other economies suggests that such steps will bear fruit.

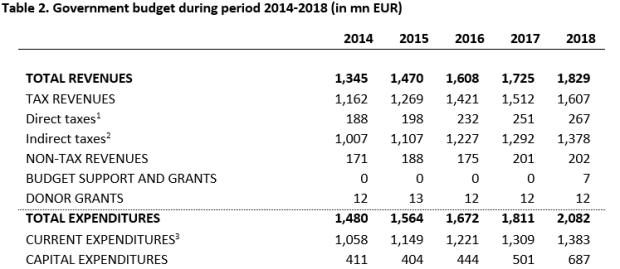

The new government’s draft budget is yet to be approved by the parliament. Estimated total expenditures are EUR 2.08bn, while revenues are estimated at around EUR 1.9bn. As can be seen from Table 2 below, most of the budget revenues come from taxation (mainly indirect taxes such as VAT, excise, etc.) while the other revenues are projected to be generated by direct taxes, non-tax revenues, and grants from different international donors. On the expenditure side, most of the money is to be spent on current expenditures such as wages and salaries, goods and services, etc., which reflects the large size of the public administration. There is also a slight increase in capital expenditure, where it is foreseen that most of the money (over EUR 600m) will be spent on roads and schools.

1 corporate income taxes, personal income taxes, property taxes, other direct taxes

2 VAT tax, custom duty, excise, other indirect taxes

3 Wages and salaries, goods and services, subsidies and transfers, current reserves

Two other key measures were included in the new budget. First, four more categories of social groups eligible for state benefits were added: paraplegics, tetraplegics, women who were sexually abused during the Kosovo war, and war veterans (qualification for the latter category is disputed). Second, it was promised that state health insurance would soon come into force, although the funding source for this policy remains unclear. If achieved, this would be a major step towards improving the well-being of Kosovo’s citizens, and could help to reduce outward migration. However, while the health sector has been bypassed so far, on January 12th the amount of compensation for social assistance schemes was increased by 20%, which should provide a small positive boost to consumption.

Several important issues left unaddressed

Aside from the government’s stated economic objective and planned fiscal reforms, four other key areas stand out as in need of decisive action:

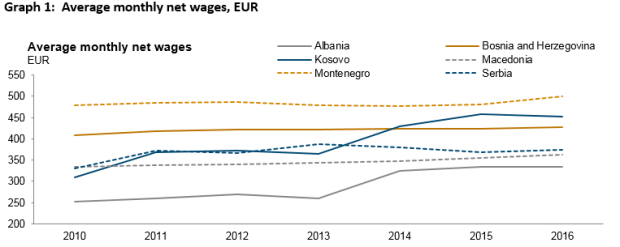

First, while more money for education is certainly positive, this ignores the quality issue. Kosovo needs more investment in improving teaching quality in an attempt to produce more competitive graduates which would match the needs of the labour market. Until now, a poor education system has led to a diploma inflation situation. Kosovo’s poor education system was also highlighted by an OECD study on education (PISA) in 2015. Even though Kosovo’s low per capita GDP limits its ability to move up the international rankings, there are policy mechanisms available to the government to improve the situation, such as investing in reforms that increase teaching quality, including newly-designed curriculums, interdisciplinary approaches etc., which would keep Kosovo in line with regional and international developments in the field of education. In addition, Kosovo’s unfavourable level of labour productivity compared with regional peers may be attributed partly to this fact. Although data on labour productivity comparison is missing, Kosovo’s high average net wages (Graph 1) comparing to its exports may be an indicator.

Source: wiiw Annual Database

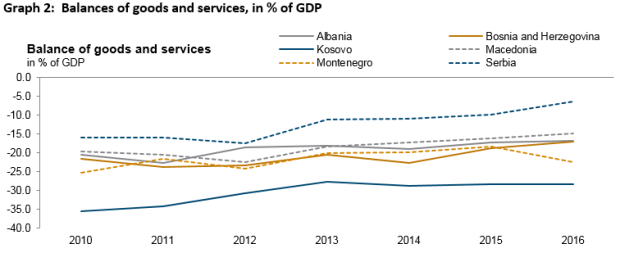

Second, the decision to raise wages in public sector by 4% in line with the trend of GDP growth, and the plan to significant further increase the number of public employees, are additional concerns. This could exacerbate Kosovo’s low labour productivity, increase the impression of the labour force (willing or unwilling) that the public sector is more attractive than private sector, and see a further rise in the tax burden on the private sector. This gives indirect incentives to the private sector to channel their operations through the informal economy, which in turn affects the government’s revenues. Given that salaries paid to the public sector are used mainly to purchase imported goods and services, capital will continue to flow abroad, contributing further to the deterioration of the country’s trade balance, and further solidifying Kosovo’s position at the bottom of the list comparing to other regional peers (see Graph 2 below). Despite all these warnings, the new prime-minister increased the salaries of the new cabinet hurting country’s budget further. Ironically, the poor country will have the highest paid prime-minister in the region.

Source: wiiw Annual Database

Third, there is still no clear plan on how to boost Kosovo exports. Low domestic production has been a problem since the end of the Kosovo war of 1998-99, and remains one of the reasons for the country’s huge trade deficit. Besides solving political issues with some neighbouring countries, there is an urgent need to identify and develop potential sectors in which Kosovo may have a comparative advantage. One development that could lead to increased exports is the new government’s plan to revitalise the ‘Trepça’ mining complex. While this may take some time and major analyses are needed, one of the ideas put forward recently is to separately revitalise each segment of the mining complex, and for each of the segments the most plausible model discussed is private-public partnership (PPP).

Finally, the energy situation in Kosovo is unstable, and has for a long time has been a major impediment to Kosovo’s economic development and attraction of foreign investors. At present, most energy is imported from neighbouring countries, mainly Albania and Serbia, increasing the cost of the energy for the final consumers. Recently, there have been positive developments in this direction. on December 20th the government signed a contract with US firm Contour Global on building a new coal-fire power plant ‘New Kosova’, with the construction works planned to begin in 2018 and finish by 2023. The project is valued at around EUR 1.3bn, and is the largest investment Kosovo has had since its independence in 2008. The generated capacity is projected to around 500 mW (well below earlier projections of 2000 mW). Unfortunately, however, there is no public document available to provide more insights into the project’s mode of financing, technology applied, and other terms agreed. This non-transparent behaviour is one of several concerns relating to the project among the general public and civil society, with issues raised around the real cost of the project, and its environmental and health implications. Improving Kosovo’s energy situation is vital, but it remains to be seen whether the health and environmental costs in the future will be larger than the benefits.

Photo: Kosovo's prime minister Ramush Haradinaj