New Russian sanctions against Ukraine make little sense

06 November 2018

The latest Russian sanctions are unlikely to have much of an impact and may be even politically counter-productive ahead of the upcoming presidential elections in Ukraine.

On 1 November 2018, the Russian government imposed sanctions against 68 Ukrainian companies and 322 individuals, which notably include a freeze of their assets in Russia and a ban on asset repatriation from Russia. Among the sanctioned Ukrainian companies are some of the country’s biggest producers and exporters, spanning a broad range of sectors: from metals (such as Interpipe) and chemicals (such as Dniproazot) to agriculture (such as Kernel). The sanctioned individuals include many high-ranking Ukrainian politicians and businessmen, including Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, Defense Minister Stepan Poltorak, speaker of the Parliament Andriy Parubiy, former prime-minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, leaders of the Radical Party Oleh Lyashko, and of the Right Sector Dmytro Yarosh, as well as some of the country’s richest businessmen such as Viktor Pinchuk, Gennady Boholyubov, and Konstantin Zhevago.

The timing of the Russian sanctions is difficult to understand. Officially, they are in response to the long-standing Ukrainian sanctions against Russian businesses and individuals. However, the latter were initially imposed more than four years ago, back in 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Ukrainian sanctions have been gradually broadened over time, though, and now cover 756 Russian companies and 1,748 individuals.

List of targeted individuals appears somewhat arbitrary

Equally, the choice of the sanctioned businesses and individuals is far from being self-explanatory. Indeed, its apparent arbitrariness brings to mind that of the recent US sanctions list against Russia published in April 2018. The official wording of the Russian government – to facilitate the ‘normalisation’ of bilateral relations – suggests that sanctions are imposed against those Ukrainians whose anti-Russian rhetoric and actions are seen as an obstacle to such ‘normalisation’. While this perception is arguably justified with respect to many of the above-mentioned Ukrainian ministers and MPs, it is much less obvious with respect to some of the businessmen also on the sanction list. True, some of the oligarchs who used to be close to the former relatively ‘pro-Russian’ President Yanukovych, such as Rinat Akhmetov and the exiled Vienna-based Dmytro Firtash, are missing from the list. But the same applies also to Ihor Kolomoyskiy, who in his former capacity as head of the Dnipropetrovsk regional administration played a key role in the organisation and financing of volunteer battalions fighting against pro-Russian separatists, and otherwise has not been exactly famous for pro-Russian statements. Mr Kolomoyskiy’s absence from the sanction list can hardly be explained by his current opposition to Ukrainian President Poroshenko either (Mr Kolomoyskiy switched to the opposition, particularly after his main asset Privatbank was nationalised in December 2016). After all, Yuliya Tymoshenko, who is also in opposition (and is one of the favourites to win the upcoming March 2019 presidential elections), has made it onto the sanction list.

It is unlikely that economic damage to Ukraine, if any, inflicted by the new sanctions will be significant. Most Ukrainian oligarchs and politicians hardly keep substantial assets in Russia, which is far from being a ‘safe haven’ for foreign capital. In addition, it would be naïve to think that economic damage, even if tangible, would translate onto a political U-turn of Ukraine’s foreign policy and drive it closer to Russia’s ‘orbit’ – especially as long as Ukraine can rely on alternative sources of funding, including the IMF and Western governments. The bulk of bilateral trade between Ukraine and Russia has already been lost: between 2011 and 2017, trade turnover plunged by around three-quarters (although in 2017 it picked up somewhat, reflecting economic recovery in both countries), and Russian investments in Ukraine are no longer welcome.

Sanctions could backfire politically

On the contrary, the newly imposed Russian sanctions are likely to trigger another step in the escalation of the conflict between the two countries, with the most radical political groupings in Ukraine benefiting the most from such environment. These groups are likely to receive an additional political boost ahead of the presidential elections, which is hardly Russia’s preferred scenario.

Russia’s own track record with recent Western sanctions can be instructive in this respect. Most Russian politicians and experts have been repeatedly (and, in our assessment, rightly) questioning the wisdom of the Western sanctions against Russia, pointing to the fact that they have consolidated support among the bulk of the Russian society around President Putin (although his rating has somewhat suffered recently because of the pension reform) and have not brought about the desired change in Russia’s foreign policy targeted by the sanctions. However, it appears that Russia is falling into the same ‘trap’ of self-illusions, when it comes to its own sanctions against Ukraine.

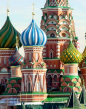

photo: St. Basil's on Red Square near the Kremlin, by Victor Nuno, CC-BY-NC 2.0