(Post-)Pandemic Employment Dynamics in a comparative perspective

04 August 2021

In the EU, fiscal and monetary policies should remain expansionary to ensure a sustainable recovery of labour markets.

By Stefan Jestl and Robert Stehrer

photo credit: unsplash.com/Silvia Brazzoduro

Policy recommendations

- Fiscal and monetary policies should remain expansionary to ensure that the nascent labour market recovery continues, allowing for a quick recovery to pre-crisis employment levels.

- As well as pressing short-term needs, fiscal policy should focus on supporting the EU’s transition to tackle challenges of the future, including the climate crisis and digitalisation.

- Policymakers need to take into account the pandemic’s divergent employment effects across industries. Employment-support schemes must be kept in place for those industries that are still suffering, and be quickly re-activated for other areas of the economy in the case of renewed lockdowns in autumn.

- Policymakers need to put particular emphasis on younger and low-skilled workers as well as those in heavily affected industries and regions. If the pandemic has caused a permanent, structural shift in the nature of work and demand for particular skills, active labour market policies must be enacted to support the transition.

- Workers lacking digital skills or those living in areas with a high reliance on tourism are likely to be particularly exposed. It is of vital importance that the social security system, rather than workers themselves, bears the brunt of this transition.

- Long-term unemployment must be minimised as much as possible. The longer that workers spend without a job, the harder it will be to reintegrate them back into the labour market.

Introduction

The economic shock induced by the pandemic has plunged the global economy into a recession. In particular, most EU economies experienced a relatively sharp downturn in economic output in 2020 as compared to other major economies such as the United States. Conversely, China even revealed a positive growth in 2020 thanks to a strong economic recovery already in the second half of last year.

Lockdowns and social distancing measures have affected economic life in a substantial way. While the whole economy was affected at the onset of the pandemic, different industries have faced varying economic difficulties throughout the crisis. The service sector, most notably contact-intensive services, were forced to temporarily close their businesses in the wake of recurring virus waves. Tourism, which in some countries makes up an important share of the economy (e.g. in Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Croatia, Austria), has been one of the most affected industries.

Governments in European economies have rolled out large public support measures to dampen the pandemic’s negative economic and social effects. While the US mostly relied on supporting incomes (via direct monetary transfers to households), European countries put more emphasis on job retention (via transfers and support to companies). The centrepiece of the public support measures in Europe has been the launch of the short-term work schemes. Throughout the pandemic, many companies have called on these programs which has helped to save many jobs and mitigate losses in household income. This is in clear contrast to the effects of the public support in the US that has not been designed to prevent job loss.

Despite the unprecedented public support measures, the pandemic has also brought a skyrocketing number of unemployed. In 2020, the COVID-19 shock hit some European labour markets even harder than the global financial and economic crisis. The emergence of new virus variants and supply problems and delays at the beginning of the vaccine rollout programmes resulted in a bumpy start of 2021. The strained labour market situation and the sluggish recovery until the second quarter of 2021 have put jobless individuals at risk of facing long-lasting scarring effects and being trapped in unemployment for a longer time. Such effects are likely to also bring negative repercussion on long-term economic development.

Recently, however, stronger global growth, as driven by the economic upswing in the United States and China, and an accelerating vaccination campaign have helped EU countries to turn formerly gloomy expectations into more positive ones (European Commission, 2021). Most recent forecasts presume that almost all European economies will reach their pre-crisis economic level by 2022. Still, high uncertainty is related to this prediction. Moreover, the pace of recovery is extremely divergent between industries. Global trade volumes have returned to pre-crisis trends, driving up demand for industrial goods. Retail sales have also rebounded, helped by easing lockdowns and ever-greater familiarity with online shopping. By contrast, industries requiring international mobility of people--most obviously, but not limited to, tourism--will take much longer to recover.

This policy brief explores potential employment dynamics across European industries by drawing on past sectoral trends and latest macro-economic forecast results up to 2026 taken from IMF and the European Commission. Using this information, employment forecasts by industries are generated for European countries and the EU-27. The preliminary results indicate that in most countries employment is expected to reach its pre-pandemic level already in 2021 or 2022 based on high projected GDP growth rates up to 4% in 2021 and 2022, while hours worked will lag behind with a full catching up just in 2022 and 2023. Even though these predictions suggest a near end of the economic disturbance caused by the pandemic, high uncertainty is related to these numbers. Moreover, special attention must be paid to the most affected population segments: younger and low-skilled workers should not be left behind in the recovery phase.

Given this background, this policy brief first summarises the employments effects of the global financial and economic crisis in 2009 and the aftermath. In a next step, the employment effects of the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 are compared to the financial crisis and the recovery period until 2019 by industry and social group. In a final step, preliminary results for the recovery paths after the pandemic are discussed. The last section concludes with policy recommendations.

Lessons from the global financial crisis 2009: the long way back

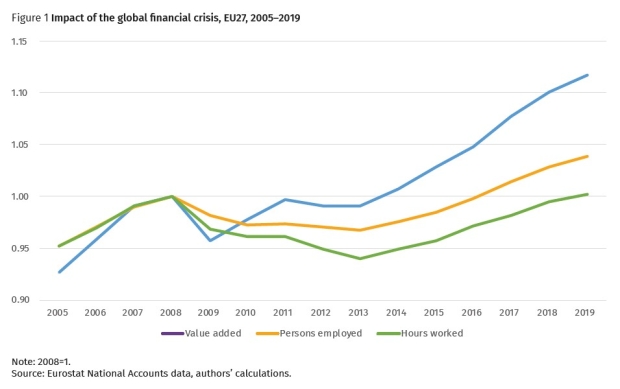

Each crisis is different, but one can learn from previous ones. Figure 1 shows the developments of the EU27 for value added, the number of persons employed, and hours worked after the global financial crisis hit the economies in 2008 and 2009. As can be seen, value added in 2009 dropped by about 4%, recovered to almost the pre-crisis level only in 2011, but then has been stagnant at this level until around 2013 due to a sluggish labour market and aggregate demand recovery, too-tight fiscal policy (e.g., Heimberger, 2017) and ongoing uncertainties in the financial markets and about the stability and durability of the euro area. Only after 2013 did a stronger recovery take hold, which was stopped by the economic fallout from the pandemic in early 2020 (which is discussed below). More importantly, the number of persons employed only recovered in 2016 and hours worked only reached again its 2008-level in 2018. Thus, it took almost a decade for persons employed and hours worked to fully recover.

An additional insight is also that labour demand responded with a delay to the economic shock. As can be seen from Figure 1, while economic activity declined dramatically in 2009, labour demand (both in terms of number of persons employed and hours worked) declined less so due to labour hoarding effects and short-term working arrangements (e.g., Müller and Schulten, 2020). However, employment levels also responded less quickly in the upturn, particularly so from the period 2010 to 2012 due to uncertainty and cautious recruitments.

Figure 1 - Impact of the global financial crisis in the EU27 from 2005 to 2019

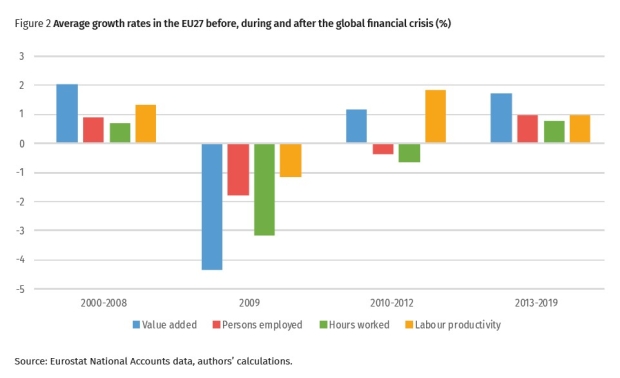

The reason for the sluggish recovery of hours worked after the hit of the financial crisis in 2009 was a low growth rate of economic activity in 2010-2012 with around 1%, accompanied by a high growth rate of labour productivity of around 2%, and a slightly lower average growth rate of economic activity from 2013-2019 as compared to the pre-crisis period 2000-2008 with labour productivity growth being at around 1%. The growth rates for the different time horizon are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Average growth rates in the EU27 before, during and after the global financial crisis (%)

Overall, this points to the fact that the recovery of employment or hours worked levels – or the labour market in general – largely depend on the macro-economic conditions and prevailing macro-economic policy decisions and the development of (labour) productivity growth after an economic shock. Further, even if economic activity is recovering quickly one should not necessarily expect a quick recovery of employment and hours worked levels which is also dependent on productivity dynamics in conjunction with labour supply dynamics.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in a comparative perspective

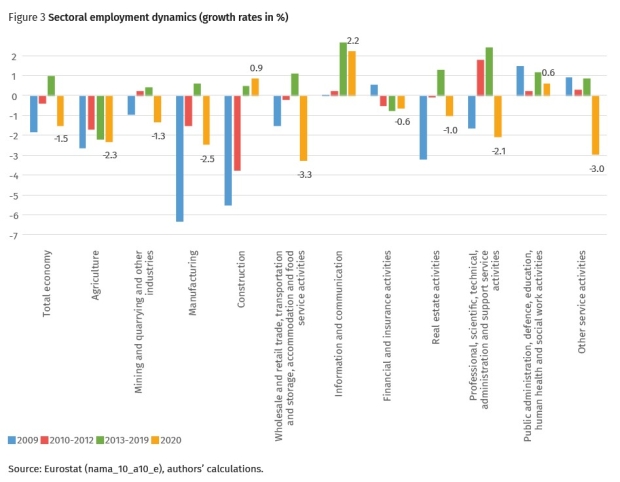

The impact of the COVID-19 crisis is of course different with respect to industries and labour market groups. Figure 3 presents the growth rates of employment (based on National Accounts data) in 2009 (financial crisis), 2010-12 (period of large overall uncertainty and euro crisis), 2013-2019 (recovery phase), and 2020 (COVID-19 crisis) allowing for a comparison across industries and over time. In 2020 employment levels dropped by 1.5%, slightly less than in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2009 (1.8%). This is remarkable when recognizing that economic activity in the EU in 2020 declined by about 6% compared to 4.3% in 2009 (European Commission, 2021). Strong employment effects have been circumvented by government support schemes, furlough schemes and short-term working arrangements together with labour hoarding effects. This has been a clear effect of the public support measures directed to companies in the EU as compared to the stronger focus on direct household income support in the US (unemployment rate in the US increased from 3.7 in 2019 to 8.1 in 2020) . In addition, economies seem to recover relatively quickly after the lockdown measures have been relaxed after the first wave of the pandemic in summer 2020 (though again declined – particularly in some industries – in the course of the second wave in autumn 2020).

Figure 3 - Sectoral employment dynamics (growth rates in %)

Figure 3 also reveals the varying impact across industries. For 2020 as a whole, wholesale and retail trade, transportation and storage, accommodation and foods service activities, and other service activities, were the hardest hit, with employment declining by 3.3% and 3.0%, respectively. Also strongly affected compared to trend growth rates of the pre-pandemic recovery phase (2013-2019) were manufacturing, real estate activities, and professional, scientific, technical, administration and support service activities. The industries with positive growth rates are construction (0.9%) and information and communication industry (2.2%). There are also remarkable differences compared to the year 2009, when particularly manufacturing, construction, and real estate activities have been hit much stronger, with growth rates in other industries having been affected much less.

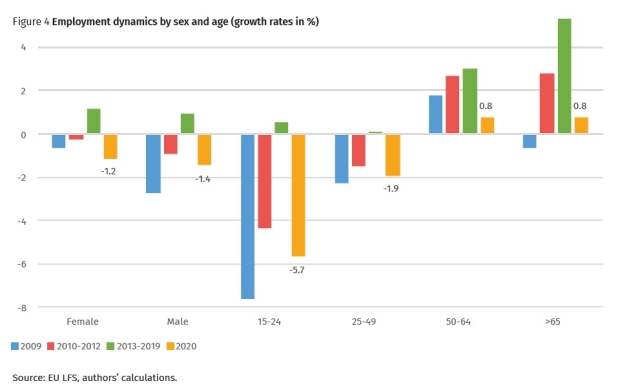

The differences in sectoral employment growth rates also imply divergent impacts on the various labour market groups which is presented in Figure 4 for sex and age groups (based on EU LFS data). Concerning sex, employment growth rates of female and male workers declined relatively similar with 1.2 and 1.4% respectively. This is different from the crisis in 2009 when the impact has been much stronger for male workers. Similar to the crisis in 2009, labour demand for young workers in the age of 15-24 declined by 5.7% (among others, due to more short-term contracts) and for the age-group 25-49 by 1.9%. Though growth rates of older age groups were also considerably lower than in the past (particularly when compared to the trend growth rates 2013-2019), these at least remained positive at almost 1%.

Figure 4 - Employment dynamics by sex and age (growth rates in %)

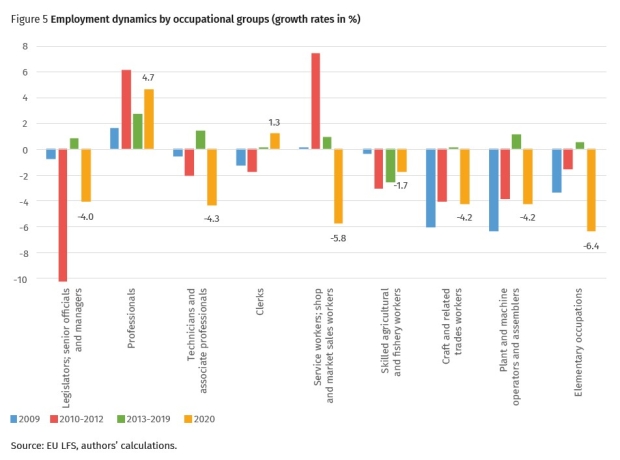

Finally, Figure 5 presents the heterogenous impact of the COVID-19 crisis on various occupational groups (associated with educational attainment levels). The most negatively affected occupational groups are elementary occupations (-6.4%), service workers, shop and market sales workers (-5.8%) with labour demand for other groups also having strongly declined by more than 4% (see Figure 5). Interestingly, a strong impact is also recorded for legislators, senior officials and managers (-4%) and technicians and associate professionals (-4.3%) which is a pattern particularly different to the global financial crisis year 2009.

Figure 5 - Employment dynamics by occupational groups (growth rates in %)

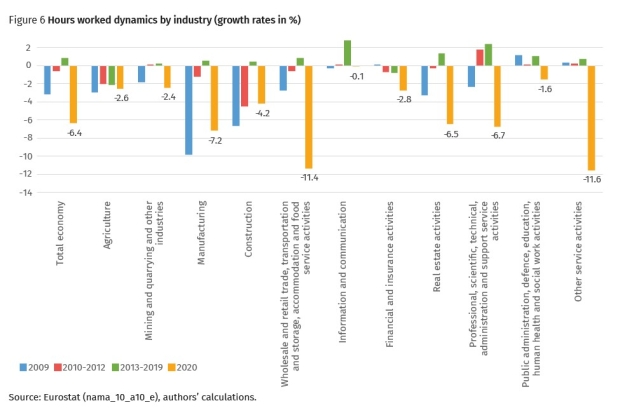

It is important to note that these data again show the number of persons employed which have been kept in place due to short-term working arrangements and furlough schemes, and probably labour hoarding by firms. Figure 6 therefore shows the decline in labour demand in terms of hours worked (comparable to Figure 3 above). Total hours worked dropped by more than 6% for the total economy (more or less corresponding to the decline in overall GDP). Hours worked in the two most affected industries (wholesale and retail trade, etc. and other service activities) declined by more than 11% followed by the three others (manufacturing, construction, and professional etc. service activities) by rates ranging from 6.5 to 7.2%. In terms of hours worked, labour demand even in information and communication services slightly declined.

Figure 6 - Hours worked dynamics by industry (growth rates in %)

Potential recovery paths after the pandemic

Having reported the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on employment compared to the global financial crisis in 2009 and the long-term growth rates, the most important question is how labour demand will evolve over the next years and by when pre-crisis employment levels will be reached again. Recent GDP forecasts by various institutions (e.g. IMF, 2021; European Commission, 2021) are quite optimistic and predict growth rates for the EU in 2021 and 2022 by more than 4%. According to IMF forecasts, growth rates from 2023 will fluctuate around 2% for the EU. These macro-economic growth forecasts are combined with industry level value added growth rates and shares over the period 2013-2019 to calculate industry level growth rates that are consistent with the macro-economic scenarios. Furthermore, using long-term growth rates of labour productivity (2013-2019) for labour productivity in terms of persons employed and hours worked allows to calculate the potential employment recovery dynamics based on the assumptions that (i) the macro-economic forecasts turn out to be accurate and (ii) the sectoral growth patterns of the period 2013-2019 of value added and labour productivity re-emerge (Note: The results presented here are preliminary. For details of this approach as well various sensitivity analysis with respect to identified policy measures, see Jestl and Stehrer [2021]).

The preliminary results suggest that employment levels in terms of persons employed might already be reached again in this year or 2022 in most countries given the strong macro-economic growth predicted in the GDP forecasts. In terms of hours worked the 2019-level will be reached about 1-2 years later due to the stronger decline in hours worked in 2020 (see Figure 6) compared to persons employed and larger productivity growth rates in terms of hours worked.

Concerning employment and hours worked at the industry level, the results point out that most industries will return to their pre-crisis levels also already in 2021 or 2022 and between 2022 and 2023 in terms of hours worked. The industries with strong growth rates – specifically information and communication industries and professional, scientific, technical, administration and support service activities – or industries with limited impact of the crisis – specifically public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities - reach the pre-crisis levels even earlier. Other industries remain at their downward trend; these are agriculture and financial and insurance activities. In contrast, the most affected industries would reach these levels only later due to relatively modest value added combined with relatively high productivity growth rates as well as the strong decline during the pandemic.

Conclusion

The calculations and results highlight a number of policy conclusions. First, in order for the labour market recovery to continue and strengthen, including in the most badly-affected industries, economic growth overall needs to be strong. That means that fiscal and monetary policies need to be expansionary. On the monetary side, this seems fairly likely. The ECB retains a dovish stance and has emphasised repeatedly that the current spike in inflation in some parts of the euro area is ‘transitory’ and will not lead to a tightening of policy. Monetary policy should also remain geared towards limiting excessive volatility and fluctuations in financial market, which can themselves have negative spill-overs for sentiment in the real economy. EU fiscal policy has also been supportive so far in response to the pandemic, albeit much less so than in the US. It is vital that fiscal support is maintained in order to underpin a quick recovery to pre-crisis employment levels and sustainably strong growth in conjunction. Fiscal support should not be indiscriminate, but rather targeted at the most pressing short-term needs, plus helping to prepare the EU economies for the most important future challenges such as the climate crisis and digitalisation. A premature return to fiscal consolidation with a harsh austerity – as happened after the last crisis – would weaken the economic recovery.

Second, for industries which have suffered the most from the pandemic and are still in danger should a fourth wave of the virus arrive, support schemes should remain in place or be quickly re-activated if necessary. This applies in particular to job retention programmes such as short-time work schemes. Limiting the direct impact of and future lockdowns on employment will be crucial to making sure that the labour market recovers quickly and sustainably after the pandemic.

Third, targeted policies are also needed for segments of the labour market that have suffered the most and might also lag behind in the recovery phase. This includes in particular younger workers who have recently or are about to enter the labour market, and groups such as low-skilled workers and those having lost jobs in industries heavily affected such as tourism. If the pandemic really has forced a structural change in the nature of employment, with for example a prolonged period of reduced tourism demand but a permanent increase in remote working and greater demand for ICT skills, policy should be geared towards supporting this transition. This means retraining schemes, special attention to regions that were particularly tourism-dependent in pre-pandemic times, and making sure that the social safety net is up to the challenge. It is vital that the social security system, rather than workers themselves, bears the brunt of this transition.

Finally, even though employment is generally currently recovering in EU countries, it will take a longer time to reach the pre-crisis unemployment level. Policymakers need to put particular emphasis on the group of long-term unemployed. Persist unemployment often results in scarring effects that are harmful for economic development. Again, this will require particular attention to certain age groups (e.g. older workers), regions (for example those most reliant on tourism), and those workers lacking skills that are likely to be increasingly important in the post-pandemic world (such as digital competence).

This policy brief is based on the baseline results from the ETUI-wiiw project on short-and medium-term sectoral employment forecasts taking into account economic sectoral restructuring during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

It has already been published as ETUI Policy Brief No. 2021.12.

References

European Commission (2021). European Economic Forecast, Spring 2021. Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Institutional Paper 149, Brussels, May 2021.

Heimberger, P. (2017). Did fiscal consolidation cause the double-dip recession in the euro area?, Review of Keynesian Economics, 5(3), 439-458.

IMF (2021). World Economic Outlook – Managing Divergent Recoveries. International Monetary Fund, Washington DC, April 2021.

Jestl, S. and R. Stehrer (2021). Short-and medium-term sectoral employment forecasts during and in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, ETUI Working Paper, Forthcoming.

Müller, T. and T. Schulten (2020). Ensuring fair short-time work – a European overview. ETUI Policy Brief. European Economic, Employment and Social Policy. No. 7.