Russia’s war in Ukraine causes a reversal of FDI trends

14 February 2023

Foreign direct investement in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe is suffering from the war. The recovery after COVID-19 came to a halt while the structure changed

By Olga Pindyuk

image credit: istock.com/simonkr

- Russia’s war in Ukraine interrupted the recovery of FDI in CESEE and has prompted significant shifts in the FDI structure.

- Russia has witnessed the large-scale divestment of foreign capital, and FDI inflows into EU-CEE have also suffered

- Meanwhile, in the second quarter of 2022 the Western Balkans and Turkey recorded higher inflows on an annual basis.

- Some parts of the CESEE region may be able to benefit from the accelerated green transition and the relocation of companies away from the war zone.

The post-COVID-19 recovery in global foreign direct investment (FDI) has turned out to be short lived, as it was interrupted by Russia’s war in Ukraine and by a combination of crises triggered by that war.[1] According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), having grown by about 35% year on year in Q1 2022, global FDI flows in Q2 2022 fell by 7% year on year, reflecting a shift in investor sentiment in an extremely uncertain environment. Announcements of greenfield investment projects – an indicator of forward trends – have also been following a downward trend, declining over the first three quarters by 10% in annual terms.

Varying trends across CESEE

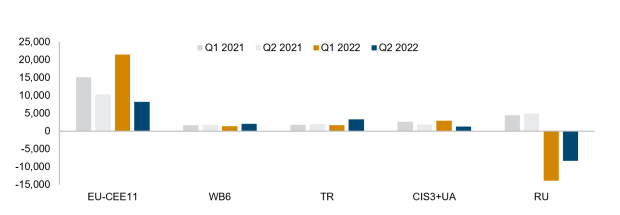

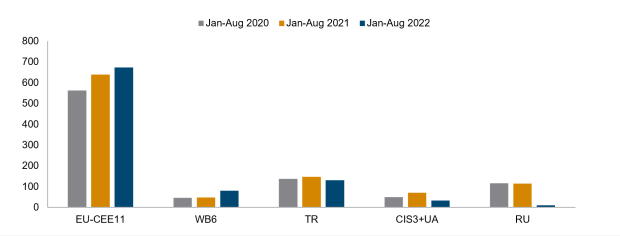

FDI activity has also been adversely affected in the CESEE region (see Figure 1), although performance has varied across the countries of the region. The biggest change has been observed in Russia: by the end of October 2022, more than 1,260 international companies (43% of all the international companies operating in the country) had ceased their operations or withdrawn from the country; moreover, an additional 495 companies (17% of all international companies in the country) had scaled down their operations or put their investment plans on ice.[2] This trend manifested itself in the large negative FDI inflows in H1 2022. Turkey, by contrast, recorded a substantial growth in FDI inflows in Q2 2022 of 70% year on year, with food processing and tourism the main sectors behind the acceleration.

After the boom of Q1 2022, when FDI inflows increased by 42% year on year, in Q2 2022 the EU member states of the region (EU-CEE) recorded an annual decline of 21% in FDI inflows. In the countries of CIS3 (Belarus, Kazakhstan and Moldova) and Ukraine, the decline in FDI inflows in Q2 2022 was even greater – 31% year on year. Western Balkans, by contrast, recorded higher FDI inflows in Q2 2022 in annual terms (whereas in Q1 2022, FDI inflows had experienced a decline year on year).

Figure 1 / FDI inflows in the main regions of CESEE in 2021-2022, EUR million

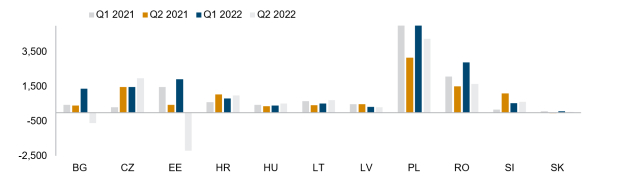

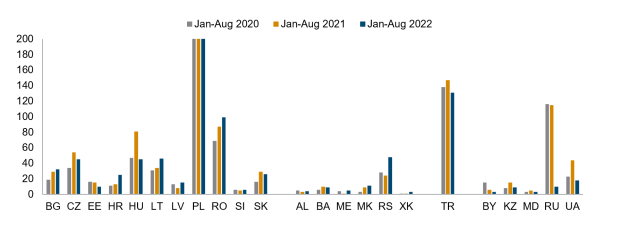

Zooming in on the performance of individual countries, one can discern quite noticeable variation in the FDI dynamics of the countries in CESEE (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). In EU-CEE, five countries (Czechia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Romania) recorded a positive year-on-year growth in FDI inflows in Q2 2022. One of the factors behind this was the relocation of enterprises from Russia and Ukraine to safer locations in the EU. By the end of August 2022, fDi Markets had recorded 57 investment projects driven by the relocation of companies due to the war, with most of them (35) having been in the software and IT services sector. At the same time, in Croatia, Latvia and Slovenia, FDI inflows in Q2 2022 declined significantly in year-on-year terms, while Bulgaria and Estonia experienced divestment (negative FDI inflows), reflecting a fall in reinvested earnings and global intra-group rearrangements.

Figure 2 / FDI inflows in EU-CEE countries in 2021-2022, EUR million

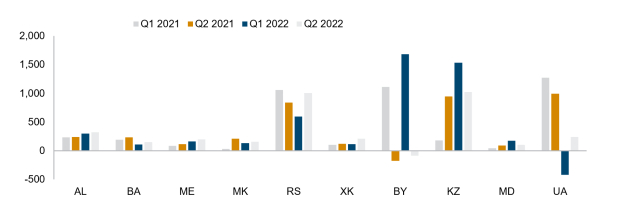

Figure 3 / FDI inflows in non-EU CESEE countries in 2021-2022, EUR million

In the Western Balkans, most of the countries recorded an increase in FDI inflows in Q2 2022 in annual terms, with only Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia experiencing a decline. The upward FDI dynamics in this subregion was likely supported by a revival of the tourism sector following the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, and possibly also by some near-shoring activity. According to Alike et al. (2022), their last survey – conducted in April 2022 – showed that while larger inventories and dual-sourcing strategies continue to be the most common supply-chain resilience measures globally, regionalisation is also gaining momentum – 44% of respondents (up from 25% in 2021) said they had been developing regionalised supply networks, and most respondents expected this momentum to continue.

In the CIS and Ukraine, quite predictably, FDI inflows have largely performed poorly. Only Kazakhstan and Moldova, which (compared to their peers in the subregion) have a relatively stable political situation, managed to increase their FDI inflows slightly in Q2 2022, primarily on the back of reinvested earnings.

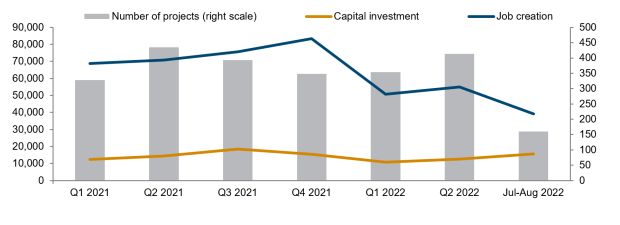

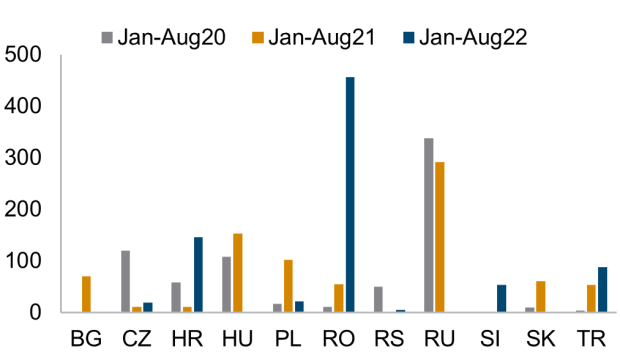

Weakening greenfield investment suggests bleak outlook

There were fewer announcements of greenfield FDI projects in CESEE in Q2 and especially in Q3 2022 (see Figure 4). Although we only have comprehensive data on greenfield investment projects for July and August, the drop in number was too great to be offset in September: in the first two months of Q3 2022, 160 projects were announced, as against 256 projects in the same period of 2021. Overall, during January-August 2022, the number of greenfield investment projects announced in CESEE fell by 9% year on year.

Interestingly, though, the value of investment projects in CESEE increased considerably in Q3: in July-August, pledged capital investment amounted to EUR 15.7bn, compared to EUR 9.8bn during the same period of the previous year. Thus, though the value of investment projects decreased over Q1 and Q2 2022, skyrocketing growth in Q3 pushed overall growth in the pledged capital values during January-August to 7% year on year. This development was driven by the sectoral distribution of the investment projects – and primarily by an increase in projects in the energy sector, which are more capital intensive than projects in other sectors.

Figure 4 / Greenfield FDI projects in CESEE: number of projects, announced capital investment in EUR million and number of jobs to be created, 2021-2022

Near-shoring and green transition offsetting headwinds in parts of the region

Looking at the development of greenfield FDI in the different CESEE subregions, EU-CEE and the Western Balkans were able to record a year-on-year increase in the number of greenfield projects announced during January-August 2022 of 6% and 67%, respectively (see Figure 5). This could be interpreted as the first signs of both near-shoring (spurred on by the need to relocate away from Russia and Ukraine, as well as from Asia, due to the COVID-19-related supply-chain issues) and an acceleration in the transition to renewable sources of energy. Other subregions, by contrast, experienced a slump in the number of greenfield projects, with Russia the worst performer (a 91% decline year on year).

Figure 5 / Number of greenfield projects announced in CESEE countries, 2020-2022

Greenfield project announcements increased in most EU-CEE and West Balkan countries (see Figure 6), with the fastest increase occurring in Montenegro (where the five projects announced in January-August 2022 meant a 400% increase over the same period last year), Serbia (100% increase), Croatia (92%) and Latvia (88%). The number of greenfield projects fell year on year only in Hungary (-44%), Estonia (-33%), Czechia (-17%), Slovakia (-10%) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (-10%). The four EU-CEE countries with declining numbers of greenfield investment projects are expected to have the weakest economic performance in the subregion in 2022, with Hungary likely to enter a recession next year (wiiw, 2022). In the CIS and Ukraine, all the countries experienced a significant decline in the number of greenfield investment projects.

Figure 6 / Number of greenfield projects announced in CESEE countries, 2020-2022

Significant structural shifts in greenfield investment

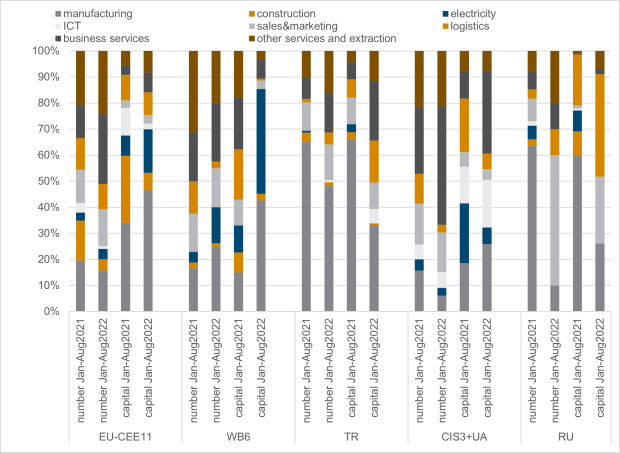

Greenfield FDI projects have undergone noticeable structural change in 2022: during January-August, the business services sector increased its share in the number of investment projects announced compared with the same period of 2021 in all subregions, while the construction sector experienced a further decline in the number of greenfield projects (see Figure 7).

Figure 7 / Share of main activities in the number and in the pledged capital investments of greenfield projects in 2021 and 2022, in %

In EU-CEE, the greenfield projects announced this year were predominantly in business services and other services and extraction, which together accounted for 51% of the total number of projects in January-August, 18 percentage points higher than in the same period of 2021. At the same time, the manufacturing and electricity sectors increased their share of the value of capital investments pledged (accounting for the bulk of them). Similar trends have been seen in the CIS and Ukraine, with business services and other services and extraction accounting for about two thirds of the greenfield projects announced in January-August 2022. The share of business services in the pledged capital in this subregion increased as well (together with manufacturing and ICT).

In Western Balkans, it was the manufacturing and electricity sectors that significantly increased their share of both the number and the pledged capital of greenfield projects in January-August 2022. The electricity sector had the most striking dynamics, with its share of pledged capital increasing fourfold compared to January-August 2021 – from 10% to 40%. Turkey and Russia stand out as the countries where logistics and sales & marketing became relatively more important in the structure of greenfield investment projects.

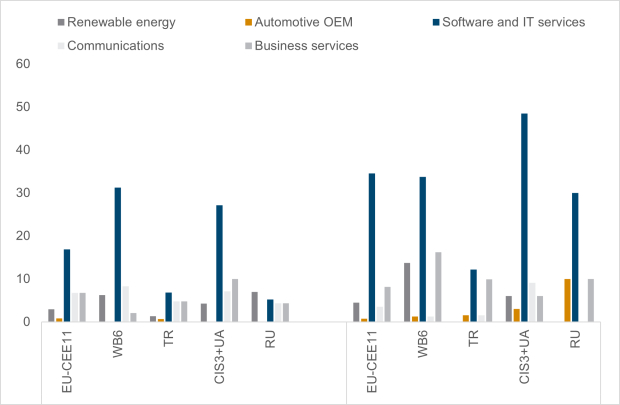

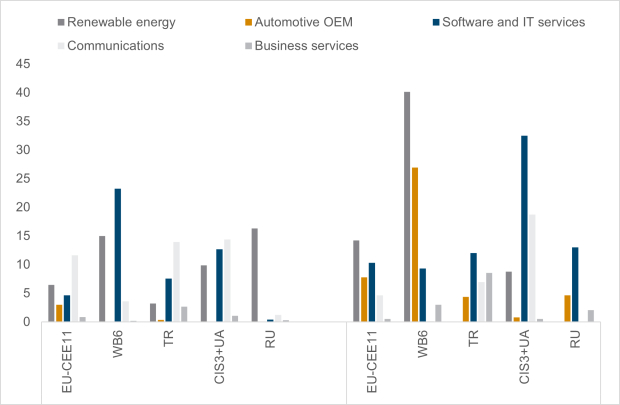

Analysis of the sector structure of the companies that are making greenfield investments in the region can shed additional light on the factors that lie behind the investment decisions. In terms of the number of projects, it is investing companies from the software and IT services sector that account for the highest share of greenfield projects in CESEE, with their share increasing in 2022 in all subregions (see Figure 8). In the CIS and Ukraine, investing companies from this sector accounted for almost half of all the greenfield projects in January-August 2022. However, projects announced by investing companies from the software and IT services sector tend to be relatively small, and therefore their share in the structure of pledged capital is much lower than in the number of projects (see Figure 9).

It is companies from the renewable energy and automotive OEM (original equipment manufacturer) sectors that tend to initiate those projects that are relatively highly capital intensive. The renewable energy sector has proved particularly attractive to foreign investors: in Western Balkans, that sector accounted for 40% of the pledged capital of greenfield investment projects in January-August 2022 (while the sector’s share in the number of projects was 14%); in EU-CEE, its share of pledged capital was 14% (against a 4% share in the number of projects).

Figure 8 / Share of main sectors of investing companies in the number of greenfield projects in CESEE in 2021 and 2022, in %

Figure 9 / Share of main sectors of investing companies in the pledged capital of greenfield projects in CESEE in 2021 and 2022, in %

Austrian investors shifting focus to the south

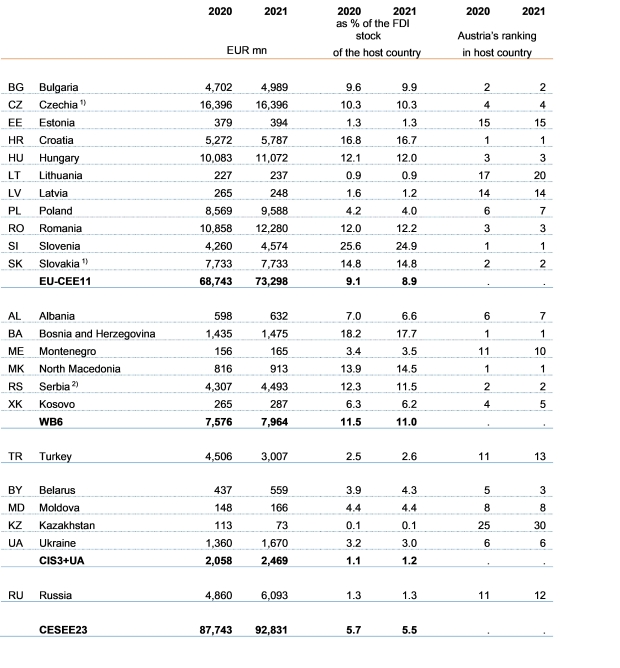

In 2021, Austria increased its direct investment position in all the countries of CESEE region except for Latvia, Turkey, and Kazakhstan (see Table 1). Though the lion’s share (79%) of Austria’s outward FDI stock in CESEE continued to be concentrated in the EU-CEE subregion, the fastest accumulation of FDI stocks in 2021 took place in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. Czechia remained the main destination of the Austrian direct investment, accounting for 18% of outward FDI stock of Austria in CESEE in 2021, followed by Romania (13%) and Hungary (12%).

From the perspective of the CESEE countries, Austria as a foreign direct investor played the most important role in Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia, where it kept its ranking of the biggest investor in 2021. In Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, and Belarus, Austria was among the top three biggest investing countries in 2021.

Table 1 / Austrian FDI stock in CESE

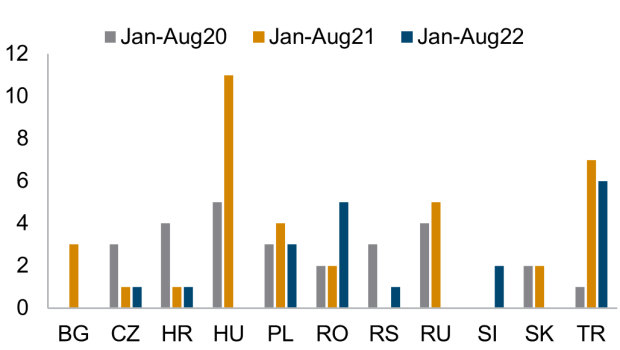

However, after the outbreak of Russia’s war in Ukraine, the behaviour of Austrian direct investors appears to have changed dramatically, as evidenced by the data on greenfield investment projects announced during January-August 2022 (see Figure 10). There were far fewer Austrian greenfield investment projects in CESEE than in the same period of 2021 (20 vs 37). At the same time, the pledged capital for the average project has almost doubled: thus the total value of the capital pledged has declined only marginally (by 4% year on year).

Over the first eight months of 2022, Austrian investors concentrated the bulk of their greenfield investment projects in Turkey (6 out of 20 projects) and Romania (5 out of 20). The change in the geographical structure of greenfield investments is even more striking when one considers the capital pledged for greenfield investment projects: Turkey and Romania accounted for 68% of the total capital pledged in CESEE, 55 percentage points higher than in the same period of 2021. Romania attracted the biggest project – worth almost EUR 400m – to be undertaken by the Austrian company Syn Trac, which plans to invest in the construction of a tractor assembly plant. Croatia has attracted only one greenfield project with Austrian capital, though it is the second largest in terms of pledged capital: the Austrian hotel and tourism group Falkensteiner announced a plan to invest around EUR 300m on upgrading its existing hotels in the region and on building a new hotel.

Figure 10 / Greenfield investment commitments from Austria in selected CESEE countries

Notes

[1] For a more detailed description of the global economic conditions and risks, see Richard Grieveson (2022), ‘Global overview: Euro area heading into recession’, in wiiw, Bracing for the Winter, wiiw Forecast Report, Autumn 2022, Vienna, October, pp. 1-7.

References

wiiw Forecast Report (2022), ‘Bracing for Winter’, No. Autumn 2022, October 2022.