Slovenia and Croatia at Sea

05 July 2017

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague has ruled on the dispute between Slovenia and Croatia over their border. A commentary by Vladimir Gligorov.

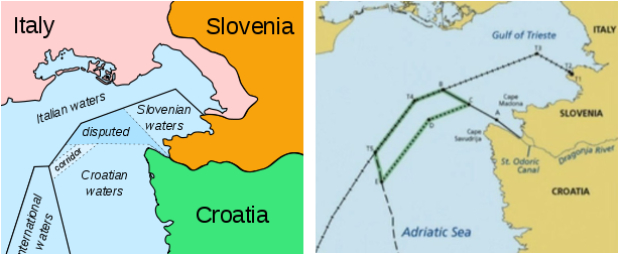

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague has ruled on the dispute between Slovenia and Croatia over their border on the land and at sea. The PCA’s decision is favourable to Slovenia when it comes to the border at the sea (see maps 1 and 2), but not on the land (not shown and not discussed here). Croatia gets to keep some of the disputed territory, while Slovenia gets a big chunk of the Piran Bay and also free entrance to international waters.

Both countries accepted the jurisdiction of the PCA because Slovenia made it a condition to vote for Croatia’s accession to the European Union (EU). Two years ago, however, Croatia pulled out of the PCA proceedings, alleging undue influence by Slovenia on the court. As a result, Croatia does not recognise the PCA’s decision, while for Slovenia it is valid. The EU, which accepted this arbitration procedure as a condition for Croatian membership, has called for the ruling to be implemented. However, it has also warned against unilateral actions. As a result, the two sides need to agree on the implementation, which they are unlikely to do. However, a prolonged status quo is not acceptable to Slovenia.

The change of the border at sea will be the most problematic; the adjustments to the land border are largely cosmetic. Currently, Croatia patrols the part of the sea which is to be transferred to Slovenia. For Croatia, nothing changes, while Slovenia expects to take over. Therefore there is a conflict.

Map 1: Pre ruling status quo Map 2: PCA’s ruling

Note: Map 1 shows disputed area controlled by Croatia. Map 2 illustrates that the disputed area is mostly allocated to Slovenia and that the corridor is widened

Sources: Map 1: wikipedia/themightyquill, CC-BY-SA 3.0; Map 2: http://www.total-croatia-news.com/politics/20056-arbitration-slovenia-gets-three-quarters-of-piran-bay

The importance of the access to international waters is probably the greatest for the competition between the port of Koper, in Slovenia, and the port of Rijeka, in Croatia (see map 3). Although Koper currently handles more cargo, Rijeka is potentially a big competitor due to its liquid gas terminal, the oil pipeline, and also because of the improved road connection with the hinterland. These two ports are quite close to each other, thus small advantages may matter for their competition. Most of the reported problems, however, involve possible changes in the conditions for fishing and possibly some tourist services on the sea. The disputed waters are good for fishing, and the interaction of the fishermen with the patrol boats are the more immediate risk for possible conflicts.

Map 3: The Peninsula of Istria

In the days following the announcement of the PCA’s decision, there have been low level incidents involving fishermen in the disputed parts of the sea, and the two governments are readying protest notes. Both sides are terribly sensitive when it comes to even the smallest parts of their territories, so it is not to be expected that Slovenia is going to be happy with the marginal concessions on land that it is supposed to make. And Croatia is going to be even less ready to concede parts of the sea that it claims for itself. Meanwhile the EU is not in the best position to intervene; it would already have used its influence had it had any, which is why the case ended up with the PCA in the first place.

In early 2000s, the Slovenian and Croatian Prime Ministers agreed to a plan quite similar to that with which the Court came up in the end, but the Croatia Parliament voted it down. At the time, Croatia felt blackmailed by Slovenia to agreeing to the arbitration as a condition for accession to the EU. If Slovenia now attempts to bloc Croatia’s entry into the Schengen system or the European Monetary Union, which may very well happen, tensions between the two countries will rise even further.

When deciding how to act, the EU needs to bear in mind the effect on the eurosceptics, especially in Croatia. Both countries are very sensitive to any change of territory for various historical reasons. That applies to all of their borders, and therefore also to relationships with other neighbours. In the past, the EU was able to persuade Italy to acquiesce to the continuity with the Yugoslav borders and also agreements with Yugoslavia, but borders between the successor states of Yugoslavia are often more contentious. Already there is speculation in Serbia about the pros and cons of turning its own border dispute with Croatia to arbitration given the PCA’s recent decision.

The dispute between Croatia and Slovenia may lead only to low level conflicts on the sea and protracted diplomatic embarrassment. A definite resolution seems unlikely with or without EU intervention, which if it were to come with conditions on further EU integration might further alienate Croatia. This is developing into a low level frozen conflict, and EU has a hard time dealing with frozen conflicts of any intensity. It also shows the limits to the politics of connectivity even within the internal EU market. Other Balkan conflicts, such as in Cyprus, are much less tractable. In most other cases, border disputes have been solved ahead of EU integration, which is probably the main lesson of Croatia-Slovenia case.