Turkey election: Erdoğan wins, but economy headed for stormy weather

25 June 2018

The large current account deficit and high FX debt rollover needs leave Turkey exposed to increasingly volatile global conditions.

Photo: kremlin.ru via WikiCommons (cropped), CC-BY-4.0

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won a clear victory in the first round of the Turkish presidential election, and will now rule with significantly enhanced powers.

- In combination with an AKP-MHP majority in parliament, the result removes the risk of prolonged economic uncertainty and/or policy stasis.

- The new government will want to help the economy as much as possible, but will be wary of overheating risks. Owing in part to a more challenging external environment, we expect the economy to grow much more slowly in the second half of the year. Questions about the independence of the central bank will remain, and the lira could weaken further.

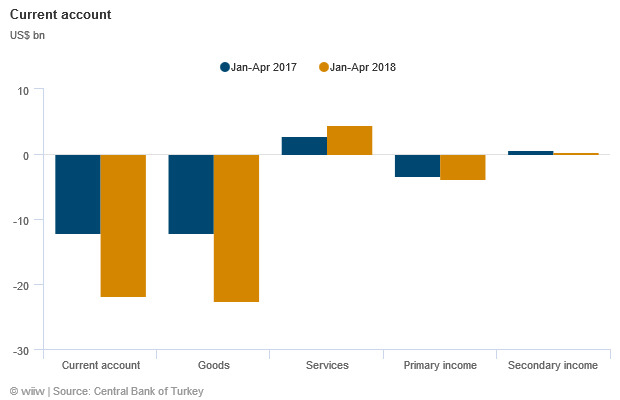

- Turkey remains highly exposed to the external environment, owing to its large current account deficit and FX debt rollover needs. As a result, Turkey is vulnerable to a spike in US inflation and tighter-than-expected Fed policy, which would force a much sharper slowdown in growth, and increase the risks of financial instability.

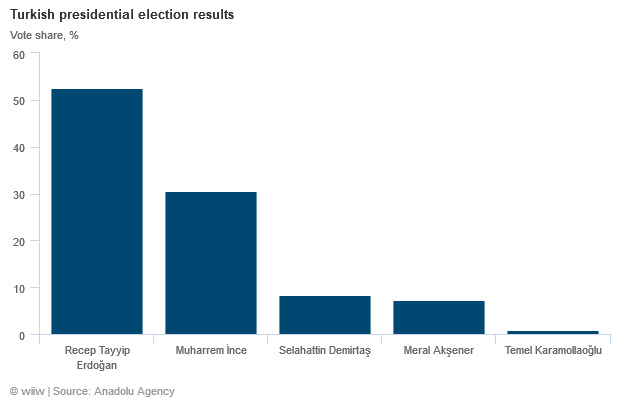

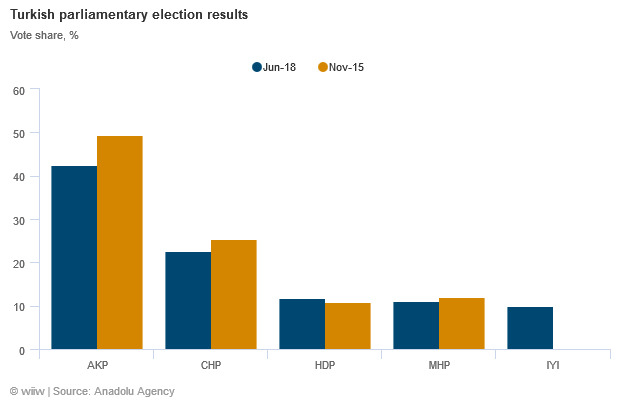

With most of the votes counted, results indicate that the incumbent, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, secured a clear victory in the first round of the Turkish presidential election held on June 24th. Mr Erdoğan took 52.6% of the vote, above the 50% required for a first round victory, and well ahead of his nearest challenger, Muharrem İnce (30.6%). In the parliamentary election held at the same time, Mr Erdoğan’s AKP took 42.5% of the vote. Together with the 11.1% won by their allies, the MHP, this is enough for an AKP-MHP majority in parliament.

While a victory for Mr Erdoğan always looked likely, the results are significant in a few ways. First, many polls in the run up to the vote had indicated that the president could struggle to get over the 50% hurdle in the first round. Second, the MHP result was perhaps surprisingly strong. Third, and maybe most important, the AKP vote in parliament fell quite significantly versus the last election in November 2015 (see chart below). This may have been partly influenced by tactical voting in favour of the AKP’s ally, the MHP, but also points to a large difference in the level of support between Mr Erdoğan and his party. Separately, the OSCE and others argued that opposition parties were not allowed fair media coverage, which could have impacted vote shares.

Short-term market relief may not be sustained

The short-term market reaction was positive, with the lira rallying. This likely reflects some relief regarding the decisiveness of the result. Various polls and forecasts had indicated that the parliament could have ended up in opposition hands, or that the presidential poll could have gone to a second round. Both of these would have created near-term uncertainty, and created the possibility of longer-term policy stasis. With Mr Erdoğan fully in control, decisive policy direction is much more likely.

However, concerns about the future direction of economic policymaking remain, and the lira soon reversed course, losing all of its post-election gains. Moreover, the president and government will be operating in a challenging global economic backdrop, which will increase the costs of missteps. We see three main trends for the economy in the next 2-3 years:

1. Slower growth

Domestically, Mr Erdoğan will want to continue to stimulate the economy as much as possible (for example with credit for smaller firms). In particular, he will be keen to maintain good recent momentum in the labour market, which probably contributed to his election victory.

However, the government is aware of the risks posed by overheating, and with the election won, it is likely to tread more cautiously than in the recent past. Turkey’s economy has clearly been overheating for some time, with inflation stuck in double digits, the currency very weak, the current account deficit uncomfortable wide, growth booming (on the back of stimulus measures) and credit growth running at over 20% year on year. A recent wiiw study found that Turkey, along with Romania, was most at risk of overheating among countries in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE).

The economy grew by 7.4% last year, and again expanded by over 7% in Q1, but this momentum will not be sustained. We think that a slowdown is coming in the second half of the year, and expect growth to be below 5% for 2018 as a whole (the government is targeting a rate of 5.5%). In 2019-20 we also expect growth rates of well below 5%.

2. Independence of central bank to remain in question

In London in May, Mr Erdoğan hinted at taking more direct control of monetary policy after the election. However, following a further Lira sell-off in June, the central bank was allowed to hike aggressively, despite the potentially high political costs of doing so. In the end, while the administration will continue to prefer lower rates, we expect it to hike when necessary, even if sometimes with an uncomfortable delay. Nevertheless, investors will continue to question the bank’s independence, and the lira is likely to remain under pressure.

3. External factors remain the biggest challenge

The main issue from the point of view of macroeconomic stability, as we have long highlighted, is the economy’s external vulnerability. The gaping current account deficit (which roughly doubled in January-April versus a year earlier; see chart below), high levels of short-term FX-denominated debt, and rising oil prices all present major challenges. As US rates continue to rise (sucking dollars back to the US), and with the lira so weak (increasing debt servicing costs in local currency terms), Turkey is clearly exposed.

So far, the US Federal Reserve is tightening slowly, and its moves are well telegraphed. These conditions have been extremely important in ensuring that an already difficult situation has not become even worse for the Turkish economy. If the Fed messaging changes—for example because of a spike in US inflation—sharply higher US rates would force a rapid contraction of the Turkish current account deficit, leading to a much more significant slowdown in growth than we currently expect, and potentially financial instability.