Ukraine’s presidential elections: entering uncharted waters

24 April 2019

Relations with Russia will not improve significantly, while future economic policy depends largely on the results of the October parliamentary election.

- The landslide victory of Volodymyr Zelenskiy in the Ukrainian presidential election should not be interpreted as an approval of his programme, but rather as a rejection of the corrupt and oligarchic-dominated system, which is deeply entrenched in Ukraine.

- With Mr Zelenskiy winning in 24 out of 25 regions, his victory is a rare example of unity in a country that has been historically torn apart by regional divisions.

- On the issue of Donbass, Mr Zelenskiy’s room for manoeuvre will be constrained by the fact that the implementation of Minsk agreements is largely seen in Ukraine as a betrayal of national interests.

- The future of economic policy remains clouded, and will largely depend on the results of the upcoming parliamentary election in October 2019.

Anti-establishment sentiment reaches Ukraine

Volodymyr Zelenskiy, an actor and comedian (but also a businessman) who became famous for being in a TV show where he becomes president by accident, enjoyed a landslide victory over incumbent President Petro Poroshenko in the second round of Ukraine’s presidential elections on 21 April 2019. Mr Zelenskiy won around 73% of the votes, compared to 24% of Mr Poroshenko. On the surface, his victory brings to mind the recent political successes of anti-establishment figures and political forces in other countries, such as the Five-Star Movement in Italy, Donald Trump in the US, and (to a lesser degree) Emmanuel Macron in France.

However, that is where the parallels end. For instance, both the Five-Star Movement and Mr Trump had clear policy views on many issues during their election campaigns and have been trying to deliver on their promises once in power, while Mr Macron can hardly be referred to as a true anti-establishment candidate, even if he did not run on a traditional party ticket. In contrast, the views of Mr Zelenskiy on many issues appear unclear and at times contradictory. His victory should be interpreted above all as a rejection of the corrupt and increasingly nationalistic five-year rule of President Poroshenko rather than as an expression of support for Mr Zelenskiy’s programme per se.

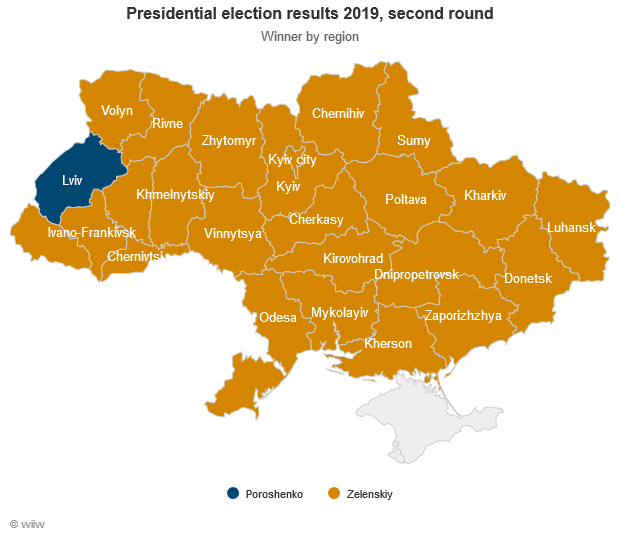

Regional divisions largely blurred

The map below shows that Mr Zelenskiy has won in 24 out of 25 Ukraine’s regions, with the only exception being Lviv oblast in the extreme west of the country (although the level of his support fluctuates widely by region, ranging between 50% in Ternopil and 89% in the Ukrainian-controlled part of Luhansk, and tends to be much higher in the South and East).

This is largely a novelty for a country which has been historically divided into a Ukrainian-speaking West and Russian-speaking East. These linguistic divisions also used to be mirrored in political divisions, with the West voting largely pro-European (and nationalistic) and the East voting relatively more pro-Russian – see, for instance, the map below which demonstrates the outcome of the second round of presidential elections held back in 2010, with the West voting overwhelmingly for Yuliya Tymoshenko and the East for Viktor Yanukovych.

Indeed, Mr Zelenskiy cannot be easily classified along these lines. On the one hand, similarly to President Poroshenko, he has advocated Ukraine’s membership in NATO and the EU, but unlike Mr Poroshenko, he stressed that these steps should be subject to a popular referendum. Similarly to Mr Poroshenko, he essentially blames Russia for the Donbas conflict and supports western sanctions on Russia, but he has also expressed readiness to talk to Russia’s President Vladimir Putin (even if only after Russia agrees to hand Crimea back to Ukraine). Also, he has criticised the previous Ukrainian policy of cutting all links with the separatist-held areas of Donbas, particularly the termination of payment of pensions on these territories, and defended the status of the Russian language in Ukraine, going against the Ukrainian political mainstream on both issues.

Thanks to these positions, Mr Zelenskiy has managed to unite the majority of Ukrainians behind him – a welcome piece of news in a country which badly needs more unity and internal cohesion.

Little room for manoeuvre on the issue of Donbas

The rhetoric of Mr Zelenskiy suggests that he may be somewhat more pragmatic and flexible than President Poroshenko on the issue of Donbas and relations with Russia in general. However, his room for manoeuvre will be constrained by the fact that any compromise with Russia will be seen in large parts of Ukrainian society as a betrayal of national interests. The Minsk II ceasefire agreement, which envisages among other things extensive autonomy for the separatist areas of Donbas and an amnesty for rebel fighters, was signed by Ukraine from a position of weakness (following several military defeats), and it is little wonder that the agreement remains deeply unpopular in Ukraine.

Indeed, Mr Zelenskiy has called for an overhaul of the Minsk II agreement, suggesting among other things to add to the current so-called Normandy format of negotiations (which currently includes Ukraine, Russia, Germany and France) also the UK and the US. However, it is difficult to see how substantial changes to the Minsk agreement can be made without the consent of Russia, so that the current status-quo – a semi-frozen conflict, which in the best case can be completely frozen – is still the most realistic scenario for the foreseeable future.

Economic policy: waiting for parliamentary elections

Ukraine is a parliamentary-presidential republic, and economic policy is – strictly speaking – not in the competence of the president, but rather of the prime minister and the government in general (the president only appoints a foreign minister and a minister of defence). The latter will be formed by a parliamentary coalition following the next elections scheduled for 27 October 2019.

However, it is fairly obvious that the newly elected president and his team will be able to exert substantial influence on the process of coalition-building. The chances are high that Mr Zelenskiy, who may be seen as a ‘political locomotive’ in parts of the political establishment, will be able to form his own faction which will likely enter a new coalition. Besides, the defeat of Mr Poroshenko in the presidential elections may put an end to the current fragile coalition between his party and People’s Front of former prime-minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, potentially opening the prospects of parliament dissolution and early elections.

This puts a lot of question marks over the future economic policy course, given the fact that the election campaign of Mr Zelenskiy on matters of economic policy was particularly light. One exception was the issue of fighting corruption (and reducing the influence of oligarchs more generally), although it included some highly controversial ideas, such as the possibility of anonymous reporting of corruption cases. Also, it is difficult to see how fighting corruption can be realistically implemented given Mr Zelenskiy’s perceived close links to Ihor Kolomoyski, a disgraced oligarch who has been at odds with the regime of President Poroshenko especially since the nationalisation of Mr Kolomoyski’s (essentially bankrupt) Privatbank in December 2016 – one of the rare triumphs of public interest over vested oligarchic interests in Ukraine. Indeed, three court rulings which were adopted last week in favour of Mr Kolomoyski (including one on the illegality of Privatbank nationalisation) demonstrate how difficult it will probably be to reduce the influence of oligarchs in Ukraine.

photo: iStockphoto/andriano_cz