wiiw Opinion Corner: Kosovo’s arbitration ‘games’

08 May 2017

What is the reason for the numerous business disputes between the government of Kosovo and foreign enterprises? Pëllumb Çollaku, guest researcher at wiiw, tries to give an answer.

Reduced barriers to entering Southeast European (SEE) countries have attracted foreign investments into the region, e.g. through the privatisation process or horizontal foreign investments in the manufacturing sector and in services, etc. Such relaxation of barriers lured also foreign small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) which engaged in tender bids in countries in the region. Of course, the new SEE market challenged the businesses which were faced with new countries, partners, cultures and trade usages implying new risks. Hence, it is not surprising that these international business opportunities gave rise to numerous business disputes. In 2016 alone, the Republic of Kosovo lost three disputes against foreign investors in international arbitration tribunals.

Almost seventeen years after the end of the war and nine years after independence, Kosovo still faces huge problems in public procurement. Despite the long-time presence of several international organisations and two large-size international missions – UNMIK (United Nations Mission Interim in Kosovo) deployed since 1999 and EULEX (European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo) deployed since 2008 – and also numerous international and local trainings offered to government agencies and public enterprises on advancing procurement processes, it seems that the lesson has still not been learned. Various violations of law and procurement regulations by the government agencies and public enterprises cost the national budget millions of euros. According to NGOs such as Lëvizja FOL and Kosova Democratic Institute – KDI, local independent press and the Kosovo Chamber of Commerce, this is due to the clash of several vested group interests, corruption and the irresponsibility of public officials. Likewise, the European Commission in its 2016 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy again criticised Kosovo for its high-level corruption, including in public procurement, and called for monitoring the public procurement processes and providing higher accountability.

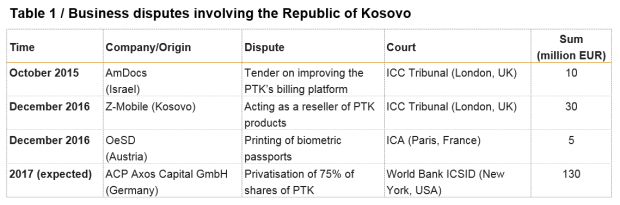

Within a just one year, Kosovo has lost three cases on business disputes after it unilaterally breached the contracts with winning companies, and the big one is yet to come – the cancellation of the privatisation of 75% shares of PTK (Post and Telecommunication of Kosovo) – see Table 1. In fact, PTK featured in nearly all such disputes, and also tops the list of violations of procurement procedures (KFOS – Kosovo Foundation for Open Society and ÇOHU – Organisation for Democracy, Anticorruption and Dignity, 2015).

Since arbitration still remains the primary dispute resolution mechanism in international trade, these companies filed their dossiers in several tribunals to seek their rights emanating from the contracts.

It began with AmDocs (Israel), the company which was awarded by PTK with a contract to develop a joint billing platform for its two business units – VALA (mobile telephony) and Telecom (landline telephony, IPTV and internet services). The contract was suspended unilaterally by the Ministry of Economy and Finance just eight days after the contract had been awarded (Raporti I Monitorimit te Prokurimit – Lëvizja FOL, 2014). This prompted the Israeli company to bring the dispute before the ICC’s (International Chamber of Commerce) Tribunal in London. The case resolution in October 2015 adjudicated in favour of the Israeli company, obliging Kosovo to recoup the amount of EUR 10 million to the company.

The second lost dispute, between Dardafone LLC (Kosovo), operating under the trading name Z Mobile, and PTK, had its roots in the blurred initial terms and conditions of a 2008 agreement between these parties awarding the former the right to act as the mobile telephony operator using PTK’s infrastructure and technology but questioning the fact whether Z Mobile had the right of access to new infrastructure and technologies applied by PTK. Even though the latter argued that it had no such obligations, the ICC Tribunal (London) concluded in favour of the claimant, awarding Z-Mobile with over EUR 30 million in lost profits and contractual penalties (including an annual accumulated interest on lost profits – 8%). In addition, specific performance under the agreement and full access to PTK’s infrastructure resources to 3G and 4G networks was allowed (ACERIS Law, 2017). Such behaviour of the publicly-owned enterprise reminds us the so-called tunnelling practice, which was defined by Johnson et al. as ‘the transfer of assets and profits out of firms for the benefit of those who control them’.

The third case was the dispute with the company OeSD (Austria), which was awarded a contract to print Kosovo’s biometric passports (the process ended with a bribery scandal of the parties involved and imprisonments of some of the people related to the deal). This corruption affair, which involved also Kosovo government officials, led the government to immediately and unilaterally cancel the contract with the company, without considering the consequences of its impulsive behaviour. This negligence of formal procedures and poor commitment to the contract cost Kosovo another EUR 5 million in the dispute resolved by the ICC Tribunal in Paris in December 2016.

However, the biggest dispute is yet to come, and that will be with ACP Axos Capital GmbH (Germany) regarding the privatisation of 75% of PTK shares. ACP Axos sued Kosovo at the World Bank’s ICSID (International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes) (EUR 130 million) for cancelling the contract, while the Kosovo government argues to have acted correctly and due to internal procedures. We can presume that such action was taken on account of conflicts between vested interest groups.

What was the reason for the cases of unilateral breach of contract by the Kosovo government, which have resulted in these losses? It may be explained by the behaviour of a small number of firms, groups of kleptocratic politicians and other groups of interest which aim to shape the rules of the game to their advantage through the illicit, non-transparent provision of private gains to public officials. Such an explanation would be in line with the ‘state capture’ hypothesis put forward by Hellman et al. (2000). This behaviour leads to corruption, which may be regarded as a key obstacle to Kosovo’s transition reforms. Potential culprits are also international institutions operating in Kosovo. Their officials were involved in numerous corruption scandals in public procurement practices and in monitoring the rule of law, such as those relating to the Kosovo Energy Corporation, EULEX, etc.

These instances of corruption are certainly having various negative effects on the society and economy of the Republic of Kosovo. They slow down the country’s development and add to the lack of trust in the government, to the poor rule of law, and impair education and health services, etc. They also affect taxpayers who indirectly have to pay for such behaviour, contribute to unemployment, and send a negative signal to foreign investors.

Preventing arbitration disputes would be the first-best choice. When a contract is signed by a state or a state-owned entity, the partner needs to verify whether the entity has the power under its laws to agree to arbitration or ADR (Alternative Dispute Resolution) methods (i.e. all means of preventing and resolving disputes with the help of a third party, other than through the courts and through arbitration, e.g. mediation) which is suggested also by the International Trade Centre (2016) in settling such disputes. Furthermore, under what conditions and by whom such an agreement can be signed plays also important role.

Given the facts of state capture and the ignorance of the Kosovo government, I remain however pessimistic whether, in advance of signing new contracts, the necessary procedural steps will be taken in order to avoid difficulties before a dispute has arisen. As a consequence, the Kosovo government will likely continue to send negative signals to foreign investors, which will impede the development of the country’s business environment, and this will imply more disputes.

Pëllumb Çollaku is a guest researcher at wiiw and a doctoral candidate at the Doctoral School of Economics, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy.

photo © www.gograph.com / argus