2017 Western Balkans Summit in Trieste: the quest for a common market

12 July 2017

A regional common market would not be game changer for the Western Balkans. Focusing on higher public investment and extending collective bargaining in industry would be much more beneficial.

By Mario Holzner

Photo credit: Hot 500, Petur (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

- With further EU accession likely to be quite far in the future, the Berlin Process provides an important means for Western Balkan countries to use effectively their time in the ’waiting room’.

- Ahead of the next Berlin Process summit starting today in Trieste, Western Balkan countries have added the discussion of a regional common market to the agenda.

- However, while this could have a positive impact, it is unlikely to be decisive in increasing intra-regional trade. The main barrier to higher intra-regional trade is lack of demand.

- In our view, policymakers should focus on areas of reform likely to produce bigger benefits for the region, such as higher public investment in infrastructure and an extension of collective bargaining in order to control the real effective exchange rate.

The accession of additional countries to the EU is not high on the European Commission’s agenda. However, this does not mean that the region has been abandoned by Brussels. A potential glimmer of hope for the six Western Balkan states is the so-called ‘Berlin Process’ initiated by the German chancellor Angela Merkel in 2014. After similar events held in Berlin (28 August 2014) and Vienna (27 August 2015), the most recent summit was in Paris on 4 July 2016. There the heads of government, foreign ministers and the ministers of economy of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, as well as Croatia, Slovenia, Austria, Germany, Italy and representatives of the European Union and the International Financial Institutions, once more confirmed the will to support the Western Balkan’s path to EU accession.

The Berlin Process is centred on the issues of youth cooperation and connectivity in the fields of transport and energy, as well as the promotion of regional cooperation. Moreover, close cooperation along the Western Balkan migration route and the fight against terrorism and radicalisation were declared as common aims. In preparation for the next summit, hosted by Italy in Trieste on 12 July 2017, the six prime ministers of the Western Balkans added the issues of increasing efforts to prevent and counter corruption and especially of further Western Balkans economic cooperation – discussing a common market – to the agenda.

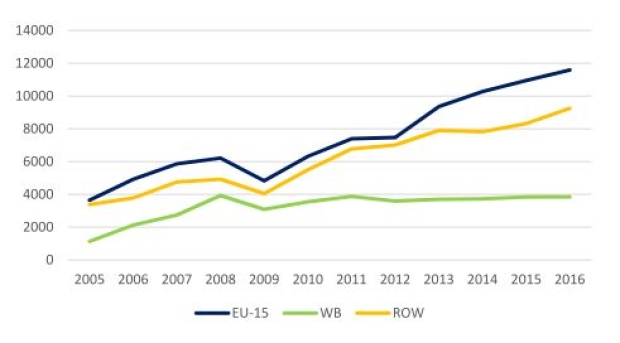

Figure 1: Western Balkans aggregate goods exports by region, in EUR mn

Note: including intra-regional trade; EU-15: EU member countries prior to eastern enlargement 2004; WB: Western Balkans six economies; ROW: rest of the world.

The main barrier to intra-regional trade is lack of demand

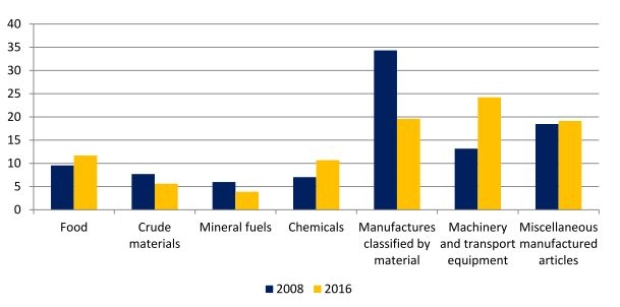

In this context it is interesting to note that since 2008 intra-regional exports have stagnated in the Western Balkans in nominal terms (Figure 1). Over the same period exports to the EU-15 have roughly doubled. This is also reflected in the change of the export structure. There, the share of higher-tech machinery, cars and chemical products exports (mostly shipped out of the region) increased by 15 percentage points on account of simpler manufactured goods classified by material, between 2008 and 2016 (Figure 2). This in turn is mostly related to more foreign direct investment (FDI) in medium-higher-tech sectors, especially in Serbia and Macedonia, in recent years.

Figure 2: Western Balkans aggregate goods export shares, in % of total, by main commodity groups, 2008 and 2016

Note: including intraregional trade; data relates to the main SITC groups 0, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8.

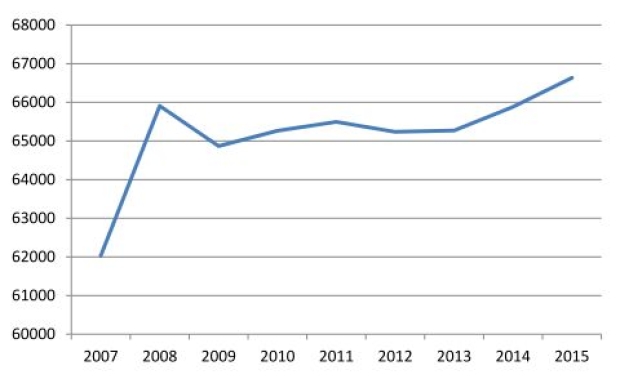

Hence, one can conclude that exports to the EU-15 are supply-constrained (i.e. driven by FDI inflows) while intra-regional trade is demand constrained. This is backed by the fact that Western Balkan aggregate final consumption has mostly stagnated since 2008 (Figure 3). This is mainly due to a drop in Serbia, the region’s biggest country.

Figure 3: Western Balkans aggregate final consumption expenditure, in EUR mn at 2010 prices and exchange rates

Common market would have positive impact, but real gains lie elsewhere

Thus, could more economic integration beyond the current Central European Free Trade Agreement – a Western Balkan ‘common market’ – increase intra-regional trade? While the introduction of a common market could, for example, further reduce waiting times at regional borders, this is unlikely on its own to underpin a sharp improvement in trade between the Western Balkan countries.

Our view is that policy makers would achieve much more progress by focusing on other areas. Two stand out. First, more EU-co-financed public infrastructure investment in the region could have the potential to serve both goals: more intra-regional trade via more domestic growth and more extra-regional trade via more FDI (attractiveness). At present, deficient regional transport infrastructure is a significant barrier to trade and wider economic growth.

Second, in the longer term and in order to be competitive in international markets, the Western Balkans need to control their real exchange rates as most of them have more or less fixed nominal exchange rate regimes. One way to control the real exchange rate is to develop a proper social partnership of employers and employees organisations that could be the basis for an income policy via collective bargaining agreements. Some of the countries from the Berlin Process initiative, such as Germany or Austria, could help given their significant expertise in this field of economic policy. This could be an area of discussion for the next Western Balkan summit in 2018.