Brexit: Small economic impact, but huge political risks ahead

29 March 2017

The economic impact of Brexit on EU Member States is likely to be modest. Much more concerning are the political challenges and risks. A note by Robert Stehrer & Richard Grieveson.

Photo: William Murphy, CC-BY-SA 2.0

- Whatever the outcome of the UK-EU27 negotiations on their future trading relationship, the economic impact will be negative. However, it is unlikely to be significantly so, and the burden will fall disproportionately on the UK side.

- In other areas, the fallout for the EU could be more material. The EU budget is likely to be reduced in size, while migration to the UK for citizens of the EU27 will not be as straightforward as is currently the case.

- However, maybe the biggest impact will be political. The negotiations could reveal important differences of interests between member states, which will be hard to reconcile.

The decision to invoke Article 50 by Theresa May marks the beginning of an intense period of negotiations to organise the future relationship between the UK and the remaining EU-27. These negotiations will last for at least two years.

Although almost one year has passed since the UK referendum on 23 June 2016, when 52% of British voters voted for ‘Brexit’, the specific shape of the post-Brexit agreement that the UK is aiming for remains unclear. However, UK Prime Minister Theresa May has indicated two key priorities: Restoring full control over immigration, and ending the European Court of Justice’s jurisdiction in the UK.

This means that the least economically disruptive post-Brexit model – the UK becoming member of the European Economic Area (EEA) like Norway – is not an option, as it would require free movement of people between the EEA and the UK. This also holds for the ‘Swiss option’, which would also require the continuation of free movement of people. Therefore, it has become more likely that the starting point of the negotiations over the future relations is a ‘hard Brexit’, implying that the UK will seek only a kind of free trade arrangement with the EU-27 (e.g. similar to the free trade arrangement with Canada), and will fall back to WTO rules in the most pessimistic scenario. Many in the EU are likely to be keen to ensure a close and mutually beneficial relationship with the UK after Brexit; however the EU cannot allow for extensive cherry-picking from UK side, meaning that the EU-27 position is likely to be quite tough.

Trade impact manageable, but worse for UK exporters

What would the consequences of this scenario be? Despite several areas of uncertainty, a few things are clear. First, the economic impact will be negative. Trade flows will be disrupted by uncertainty and the (likely) reintroduction of at least some non-tariff measures.

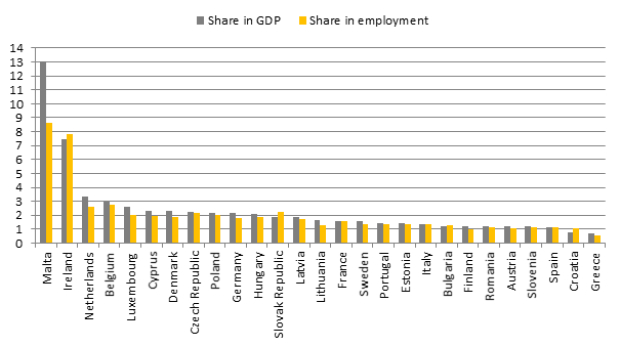

Second, the negative consequences for the UK will be much higher than those for the EU-27, although the exact magnitudes differ somewhat between countries. The EU-27 takes almost 50% of UK exports, whereas the shares of the EU-27 Member States of exports to UK are much smaller. Taking into account indirect flows to the UK as well (i.e. exports of a country to Germany which is then exported on to the UK) the dependency of the EU Member States on the UK are rather small both in terms of GDP or employment. With a few exceptions (notably Malta and Ireland) these range between 1 and 2% in most cases (see Figure above). A similar asymmetry in the relationship is also evident for more specific trade items (such as manufactured goods or services) and foreign direct investment patterns.

Third, given the relatively small shares of most EU-27 Member States exports to the UK (in % of GDP), it is commonly agreed that the impact of a fall-back to the WTO rules (as the most pessimistic scenario) on GDP and jobs in the EU-27 Member States would be negligible. Various study results point towards a cumulated negative impact in the range of 0.1-0.5% over a 10-year period (although magnitudes differ between countries).

Such calculations do not take into account potential impacts on the distribution of foreign direct investment across the EU (both from inside and outside the EU Member States). This impact is hard to predict and might depend very much on the details of the future UK-EU27 relationship and how other policies evolve (such as corporate tax rates in the UK after Brexit). Another factor of uncertainty is the future development of the exchange rate between the pound and the euro. For services trade regulations and pass-porting rights for financial institutions it is hard to predict where negotiations will go. Michel Barnier, the European Commission’s chief Brexit negotiator, has said that the EU needs continued access to the city of London past-Brexit.

The political implications make everything else look straightforward

While the economic negotiations look set to be extremely complicated, the political fallout could be even more important for the future development of the post-Brexit EU, UK, and the relationship between the two. A key issue is the future of the EU budget, to which the UK is a significant net contributor (its average annual net operating balance was EUR -7.3bn in 2010-15, the second biggest after Germany). There are various ways that part of this shortfall could be made up, such as higher tariff income in the case of WTO rules, revenues from the ‘EU Brexit bill’ (i.e. UK liabilities and assets), and potential further contributions of the UK to the EU budget in specific areas (such as defence or R&D). There is also a possibility that the UK will continue to pay for some access to the single market. However, the idea that the full shortfall will be made up by increased contributions from other wealthy member states is fanciful to anyone following domestic political debates in Western Europe.

A second aspect is migration and labour mobility, which is a sensitive issue for all EU member states. Around three million EU citizens reside in the UK (4.5% of the UK population), whereas about 900,000 UK citizens live in the EU-27 countries (0.3% of the EU population). Although it is likely that EU citizens already living and working in the UK will be allowed to do so after Brexit, this depends on the outcome of the negotiations and generates uncertainty. A related issue is whether those who would have emigrated to the UK in the future will now stay in their countries or go to other EU member states, and if the latter which ones. No other EU state has the UK combination of a large size, strong employment growth, an attractive university sector, a flexible labour market, and the English language.

Finally, the intra-EU political challenges which could emerge during the negotiations are potentially quite serious. Although at present EU member states have demonstrated impressive unity with regard to Brexit, this is not guaranteed to last. Significant differences could emerge regarding trade and single market issues (in part depending on the importance of particular industries for particular countries), freedom of movement, and how a smaller EU budget should be spent. In combination with the (lack of) sharing of refugees between member states, infringements of EU law in countries such as Poland and Hungary, the Donald Trump presidency, and continued frictions over how to address the euro zone crisis (in particular regarding Greece), this presents a formidable set of challenges for EU policymakers in the coming years.