Can Iran’s economy survive as Trump returns, war threatens and its population seethes?

04 December 2024

Decades of mismanagement, sanctions and a deteriorating investment climate have left Iran in a state of economic stagnation. With public discontent growing and the political opposition gaining strength, the country faces an uncertain future

image credit: istock.com

By Mahdi Ghodsi

Iran at a critical juncture under political pressures

Iran is experiencing one of the most turbulent periods in its modern history, as the ideological policies of its authoritarian regime have plunged the nation into an unprecedented socioeconomic decline while bringing it to the brink of full-scale war with Israel – a state with far superior military capabilities. Growing public discontent over worsening living conditions, coupled with external pressures and the advanced age of its ruler, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who is 85 years old, has been creating a critical juncture that could reshape the country’s future. Amid this complex and evolving landscape, this article will focus on the socioeconomic dimensions of the current crisis.

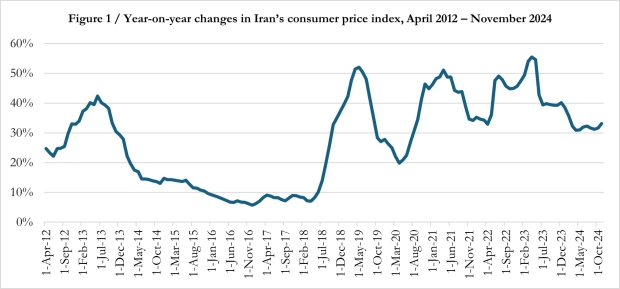

After former President Hassan Rouhani’s (2013-2021) efforts to lift sanctions and pursue rapprochement with the West collapsed following Donald Trump’s decision for the US to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the so-called nuclear deal, Ali Khamenei adopted a hardline stance. He consolidated power by ensuring a government dominated by hardliners across all branches, enabling Ebrahim Raisi – a cleric known as the ‘Butcher of Tehran’ for his participation in the mass killings of political prisoners at the end of the 1980s – to become the Islamic Republic’s eighth president. Despite his ambitions to succeed Khamenei, Raisi’s administration was marked by incompetence, implementing poorly timed and designed policies that drove the annual inflation rate to a record high of 55.5% in April 2023 (Figure 1). The failure to adjust salaries and wages of public employees (who made up 75.5% of the economy during 2017-2020 according to nominal GDP data provided by the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) and the national budget audited by the Supreme Audit Court of Iran), pensionaries and minimum wages in line with soaring inflation only increased economic discontent among the population. While this policy-induced reduction in the real income of society was justified in terms of budget-constraint reasoning, Raisi’s government allocated the budget in favour of ideological political institutions, the so-called ‘trinity’ of security-military, propagandistic and commercial-clerical apparatuses.

Figure 1

Year-on-year changes in Iran’s consumer price index, April 2012 – November 2024

Source: Statistical Center of Iran

Raisi’s hardline stance extended beyond economic matters, with his government enforcing the mandatory hijab law with unprecedented severity. This led to the death of 22-year-old student Mahsa Amini while she was in custody for allegedly violating the law that forces women to wear the hijab, sparking nationwide protests under the slogan ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’. These protests, reflecting years of pent-up societal frustration, were brutally suppressed by security forces. Raisi’s presidency came to an abrupt end when his helicopter crashed in the Varzaqan mountains on 19 May 2024. In the aftermath of this event, Khamenei sought to restore stability and quell unrest by allowing a reformist president to be elected, signalling a potential shift towards reforms as the last resort.

Economic malperformance

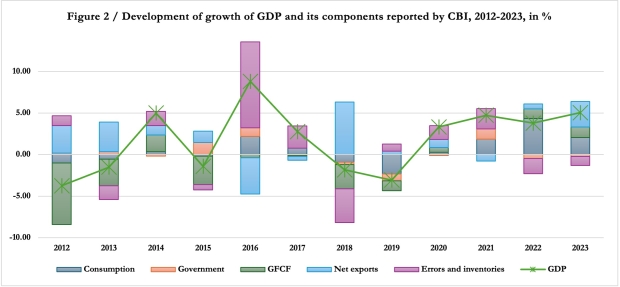

Data from the CBI underscore a decade-long decline in investment as Iran’s most critical economic development. Between 2012 and 2023, the average annual growth in gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) was -0.04%, while (as shown in Figures 2) its contribution to GDP growth was -1.13%. Given an annual capital depreciation rate of 4%, it is clear that Iran’s capital stock – the foundation of production – has been steadily eroding over the years.

Figure 2

Development of growth of GDP and its components reported by CBI, 2012-2023, in %

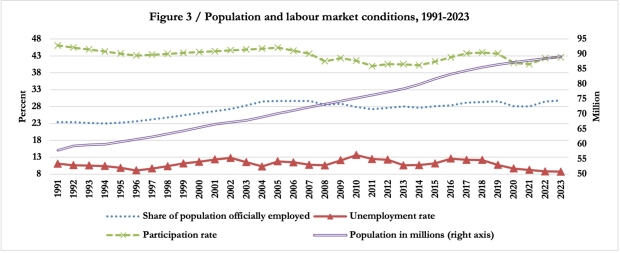

While the population and labour force have grown during this period (Figure 3), poor economic conditions and a hostile business environment – marked by extractive economic and political institutions, an expanding public sector encroaching on the private sector, economic mismanagement, stringent sanctions and Iran’s blacklisting by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an intergovernmental organisation created by Western nations to combat money laundering and terrorism financing – have significantly prolonged a period of stagflation. As illustrated in Figure 3, less than 30% of the population is officially employed, and the labour force participation rate (i.e. the share of persons in the working-age population who are either employed or unemployed and seeking jobs) remains below 43%, highlighting the adverse and discouraging nature of the country’s working conditions and labour market.

Figure 3

Population in millions and labour market conditions, 1991-2023

Source: World Development Indicators of the World Bank; author’s elaboration

This dire situation has severely worsened poverty, which now affects over 30% of the population, according to the Islamic Parliament Research Center. More than half of Iranians consume fewer than 2,100 calories per day, which is below the recommended daily intake. The crisis deepened in spring 2023 when Raisi’s administration, in coordination with the hardline parliament, eliminated the preferential exchange rate of 42,000 rials per USD due to budgetary concerns. This rate had been used to subsidise imports of essential goods (e.g. food, medicine and livestock feed). The policy change triggered a surge in food price inflation, with the annual inflation rate for the food basket exceeding 77% in May 2023, and for some items like meat and poultry by 116% or edible oil products by 202%. This forced the government to introduce a new but higher preferential exchange rate of 285,000 rial per USD by the end of 2023 to control the import prices.

Fragile oil revenues as the backbone of the economy

As shown in Figures 2, the Iranian economy grew on average by 4.51% between 2021 and 2023. A major driver during these years was growth in private consumption boosted by increasing cash handouts and subsidies. The primary driver of growth in 2023 was a substantial increase in net exports, largely driven by higher oil export revenues. According to official figures, the ‘oil and natural gas extraction’ sector recorded the highest growth in 2023, expanding by 20.3% compared to the previous year. This sector, which accounts for 16.4% of total GDP and is classified under the manufacturing industry, made a significant contribution to overall growth.

While other segments of the manufacturing industry (e.g. the ‘provision of water, electricity and natural gas’ sector, which is hampered by ageing infrastructure) experienced much slower growth or even contraction, the manufacturing industry as a whole, which constitutes 45.4% of GDP, grew by 6.9% over the last fiscal year (ending in March 2024), largely driven by oil revenues. Ironically, the world’s largest reservoir of gas and oil (combined) suffers from regular electricity outages in both summer and winter, damaging businesses and welfare. Nevertheless, the service industry, which represents 46.1% of GDP, achieved modest growth of 3.4%. The agricultural industry, comprising 7.7% of GDP, contracted by 2.2% due to drought and climate change.

Although US President Joe Biden, who was one of the key architects of the nuclear agreement (JCPOA) during his tenure as vice president under Barack Obama, was unable to revive the deal, he did manage to avoid escalating tensions with Iran and eased the enforcement of US secondary sanctions. This policy shift allowed former President Raisi’s government to export over 1.5 million barrels of oil per day (primarily to China and India) at steep discounts through a complex barter trading system. As a result, Iran managed to import USD 64.3 billion worth of goods without using the SWIFT system for bank transfers, which is controlled by the West and from which Iran was cut off some time ago. Furthermore, this complex barter trading system allows the Islamic Republic to import components needed in its missile program as well as to export military equipment, such as missiles and drones to Russia for use in its war of aggression in Ukraine. Through this system, the regime can also supply military equipment to the Houthis, jeopardising the safety of maritime passage through the Red Sea, as well as to other proxies, such as Hamas and Hezbollah, to launch attacks on Israel.

What lies ahead?

On 22 October 2024, Iran’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian, presented the budget bill for the next fiscal year, beginning on 21 March 2025, proposing a significant increase of 135% in the general government budget and a 47% rise in the budget allocated to public companies and enterprises. With current inflation at 33.1% and a similar rate projected for the coming year, this constitutes a markedly expansionary fiscal policy. Notably, while the salaries of public employees are expected to increase by only 28%, defence and military expenditures are set to skyrocket by 200%, funded through oil revenues. Such a large stimulus necessitates a steady flow of oil revenue. Otherwise, financing the resulting substantial budget deficit through the banking system could exacerbate inflationary pressures far more severely than oil revenue funding. Consequently, this budget strategy hinges on the easing of sanctions and the resolution of financial blacklisting issues.

In his first press conference, on 6 September 2024, President Pezeshkian pledged to address the challenges arising from Iran’s blacklisting by the FATF. This blacklisting has significantly increased transaction costs for trade, severely eroding Iran’s competitiveness. Even the trade of humanitarian goods, which are exempt from sanctions, has become substantially more expensive due to the restrictions linked to the FATF blacklisting.

Former President Rouhani had sought to align Iran with FATF standards by submitting a bill to ratify the Palermo Convention and the Terrorist Financing Convention. Although this bill was approved by the moderate parliament in October 2018, it was ultimately blocked by the Expediency Discernment Council, an advisory board for the Supreme Leader that settles disputes between Iran’s parliament and the Guardian Council over legislation, following Donald Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the nuclear deal.

President Pezeshkian is now also seeking to engage with Western nations to negotiate the lifting of sanctions and to attract foreign direct investment to revitalise Iran’s deteriorating investment climate. However, these efforts face significant obstacles in the current geopolitical environment. The ongoing direct conflict between Israel and Iran and its proxies (i.e. Hamas, Hezbollah and the Houthis), combined with Donald Trump’s return to the White House, makes Khamenei’s reformist overtures through Pezeshkian’s presidency appear highly unlikely to succeed. Although Pezeshkian is the second reformist president after Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), the current situation is far more dire than those years with notable economic achievements, when Iran was caught in the midst of the hawkish policies of US President George W. Bush in the region, including the invasions of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. This time, the Islamic Republic is in direct conflict with the US’s favoured ally, Israel.

Moreover, the European Union has intensified sanctions on entities and individuals involved in supplying missiles and military equipment to Russia, which could further increase the costs of trade for Iran. At the same time, in discussions, the Board of Governors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has criticised Iran for obstructing efforts to monitor its nuclear programme, while debates continue over its suspected intentions to develop a nuclear bomb as a deterrent against Israel and the US. These actions could eventually trigger the snapback mechanism of the JCPOA, which would reimpose certain United Nations (UN) sanctions before the snapback mechanism expires in October 2025. The snapback mechanism of the JCPOA allows any party to the agreement to unilaterally trigger the reinstatement of all pre-existing UN sanctions on Iran if it is deemed to be in significant non-compliance with the deal’s terms.

Donald Trump likely to further destabilise Iran

These developments paint a bleak picture for Iran’s future. Although Khamenei’s decision to allow a reformist president signals an attempt to steer the country out of its current predicament, escalating geopolitical tensions and mounting sanctions are likely to exacerbate Iran’s economic problems. If Donald Trump does not receive a convincing signal from Iran that it is willing to negotiate a comprehensive deal addressing not only the country’s nuclear programme, but also its regional proxies and its ballistic missile programme, Trump is expected to reimpose sanctions that are just as or even more severe than those imposed in 2019.

Such sanctions would severely hinder Iran’s ability to sell oil, leading to a depreciation of its currency, the rial. The resulting loss of oil revenues would place immense pressure on the government’s capacity to finance imports of essential commodities at the preferential exchange rate of 285,000 rials per USD. This fiscal strain would likely force the government to resort to printing money and expanding the monetary base, further fuelling inflation. Both of these dynamics are set to trigger a surge in prices and deepen the economic crisis.

Iran’s huge public sector is ill-prepared

Iran’s public sector (i.e. the total national budget that includes both general government budget and the budget of companies and enterprises), which is estimated to account for over 70% of GDP due to extensive government subsidies for goods and services, is ill-prepared to absorb these kinds of external shocks. Without rapprochement with the West, Iran appears to be on a precarious trajectory. While its strategic partnership with Russia and China is significant, these two countries are unlikely to provide the economic lifelines needed to stabilise the regime at this critical juncture.

This will further destabilise the regime and increase the likelihood of more nationwide unrest, particularly because the portion of the population that participated in the recent presidential elections (just 39.9% of the 61.45 million eligible voters – a record low, if reliable) expects improved socioeconomic conditions under the reformist administration of Pezeshkian, the new president. A harsher US policy towards the Islamic Republic of Iran could undermine the population’s expectations and induce a negative shock to society, potentially driving people into the streets again.

With opposition leaders both in Iran and abroad potentially better prepared to organise and mobilise protests than during previous uprisings, the regime could be confronted with much fiercer resistance and a more precarious situation, which might ultimately threaten its survival. Predictably, the regime will likely resort to its typical despotic and draconian tactics to endure, including cutting communication channels (e.g. internet access) to gather intelligence on protests during their early stages and brutally suppressing them thereafter. However, unlike in the past, tools like Elon Musk’s Starlink could play a pivotal role in maintaining the flow of information and providing protestors with counter-intelligence capabilities.

Ultimately, the fate of any potential uprising will hinge on the effectiveness of the protestors’ organisation through their leaders and the extent to which external support influences the balance of power between society and the regime.

Dr. Dr. Mahdi Ghodsi is Economist at wiiw and Senior Fellow & Head of the Economy Unit at the Center for Middle East and Global Order in Berlin.