Does Croatia’s World Cup success show that CESEE is back as a footballing power?

23 August 2018

State fragmentation and relative economic decline have seen the region’s teams generally struggle since the 1970s.

By Richard Grieveson

Photo: Luca Modric, by Fanny Schertzer, CC-BY-SA 3.0

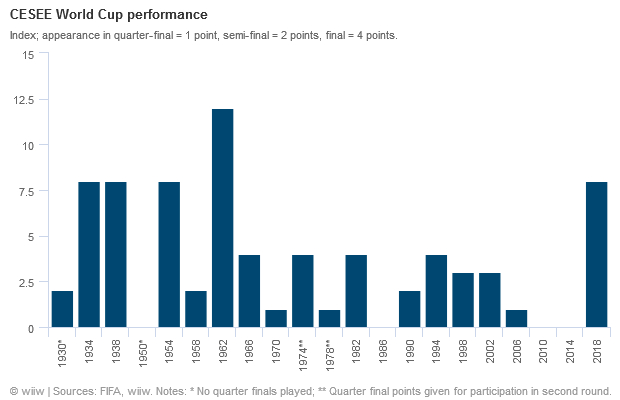

- Football teams from CESEE used to be very strong, and appeared in four World Cup finals between 1934 and 1962.

- However, since the 1980s in particular, the region has been in relative decline as a footballing power.

- This can be linked to political and economic factors. State fragmentation has significantly reduced the population size of most of the historically strong football teams in the region, while economic decline in relation to Western Europe also contributed.

- Croatia’s appearance in the 2018 World Cup final was the first by a CESEE country for 56 years, and suggests that the tide may be turning again. Most of the region’s economies are converging with Western Europe, which should help their fortunes on the pitch.

- However, Croatia’s success in 2018 likely represents an aberration rather than the start of a new positive trend for CESEE football teams.

The 2018 World Cup was held in Russia, the first time that the competition had been staged in a country in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE). CESEE was represented by four teams: Russia, Serbia, Croatia and Poland. Croatia stood out, and became the first team from CESEE to reach the final since Czechoslovakia in 1962. Russia also performed much better than many had expected, but were helped significantly by home advantage (host nations almost always do better than they otherwise would). Poland were a major disappointment, already on their way home after two games.

Region has a proud footballing history…

CESEE has a proud footballing history. Although the region has never produced a World Cup winner, CESEE teams have now reached the final five times (Czechoslovakia in 1934 and 1962, Hungary in 1938 and 1954, and Croatia in 2018). In Chile in 1962, four of the eight quarter finalists were from CESEE (USSR, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia), a particularly notable record given that historically teams tended to do less well playing away from their own continent.

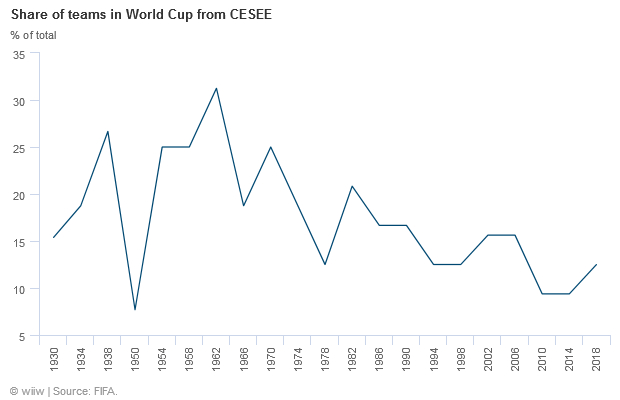

In general, CESEE’s heyday was between 1934 and 1970. During this time, CESEE contributed at least one quarter of the teams in all but two World Cups (none were held between 1938 and 1950 owing to the Second World War). As late as 1982, over one fifth of participants in the World Cup were from the region.

…but a more challenging present

Since 1982, however, the region’s football teams have been in relative decline. CESEE has on average accounted for 13% of the participation in World Cups since 1986, and this fell below 10% in 2010 and 2014. In the first ten World Cups (up to 1974) CESEE teams appeared eight times in the semi finals. However, in the next ten World Cups (up to 2014), CESEE teams have only reached the same stage four times (Bulgaria in 1994, Croatia in 1998, Turkey in 2002 and Croatia in 2018). Only three times in the history of the World Cup has CESEE failed to contribute at least one quarter finalist, and two of these were in 2010 and 2014 (the other was also relatively recent, in 1986[1]).

Of the four traditional powerhouses of CESEE football—the USSR, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Hungary—three no longer exist. Hungary of course still does, but its football team has declined dramatically. Remnants of the other three live on, most obviously in the case of the former Yugoslavia. Of the 14 CESEE participations in World Cups since 2006, eight have been by countries of the former Yugoslavia (Croatia three times, Serbia twice, and Serbia and Montenegro, Bosnia and Slovenia once each).

Why have CESEE’s football teams declined?

The decline of CESEE in footballing terms since the 1980s can be linked to political and economic factors. In their influential book Soccernomics, Economist Stefan Szymanski and journalist Simon Kuper showed that three factors determine most of a national team’s performance: wealth, population and experience. In addition, they noted that openness to outside influence, and being willing to import better ideas from other countries, also played a role. Ahead of the 2018 World Cup, the Economist built on this model, and added participation in football among the population as an additional explanatory variable.

Looking across these five factors, it is possible to understand at least some of why CESEE has declined as a footballing superpower.

1. Wealth

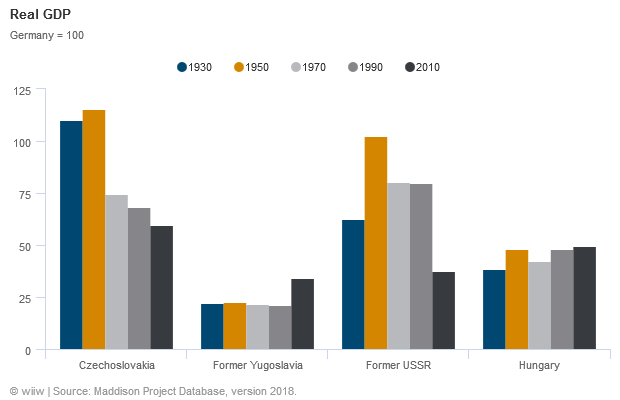

At least in the cases of Czechoslovakia and the USSR (and their successor states), declining wealth has gone hand in hand with worse performances at the World Cup. In 1930 and 1950, Czechoslovakia was wealthier than Germany, and in 1950 so was the USSR (see full Maddison data here). By 1970 both had become relatively poorer, although were still at or close to 80% of German wealth. By 2016, the picture had changed more dramatically, with the former Czechoslovakia at just over 60% of the German level, and the former USSR below 40%. For the successors of these two former unions, at least, a decline in wealth could be a contributing factor to their decline in footballing terms.

For Hungary and the former Yugoslavia, however, the trends are less clear. These two countries have never been anywhere close to German wealth levels during the period studied, and in both cases are closer to it in 2016 than was the case in 1930, 1950, 1970 or 1990. In the case of these two countries therefore, if can be said that they experienced footballing success in the 1930-1970 period despite their low income levels.

2. Population

The fact that three of the four traditional powerhouses of CESEE football no longer exist, and have been succeeded by smaller entities, probably played a very important role in their footballing decline. Despite the best efforts of countries like Croatia, the successor states of Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and the USSR have generally failed to match the achievements of their predecessors. To take one example, in the 1980s, the former Yugoslavia had a population of 23m, compared with around 14m for the Netherlands (a fairly successful Western European country). Now, Yugoslavia’s biggest successor state, Serbia, has a population of only around 7m, much less than half the population of the Netherlands.

3. Experience

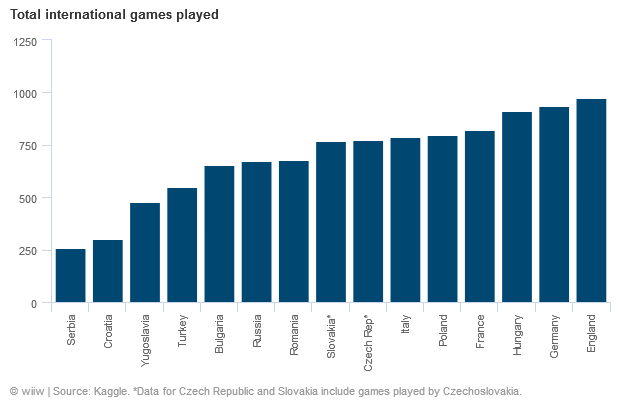

Football originally spread fairly quickly to CESEE countries, and as a result many teams in the region have similar levels of experience to the big Western European teams. Hungary has played by far the most international games among CESEE countries, followed by Poland (full data here). Hungary’s total of 912 games is actually among the highest in the world. England, for example, who started playing international games several decades earlier, have only played 67 more games than Hungary in total. Hungary have played comfortably more games than former World Cup winners Italy (785) and France (819).

Data for experience are obviously distorted by the fact that many countries are new, having previously been part of bigger entities. Czechoslovakia played 494 games, while Yugoslavia played 478. However, adding Czechoslovak games to the Czech Republic and Slovakia would propel them up to third and fourth, respectively, on the all-time CESEE list, and very close to the level for Italy. Experience therefore is not a clear explanation for why CESEE has declined, although it may be that in relative terms, CESEE team’s advantage (and indeed that of the big Western European and South American teams) in experience over many other parts of the world is less important than it was.

4. Participation in football

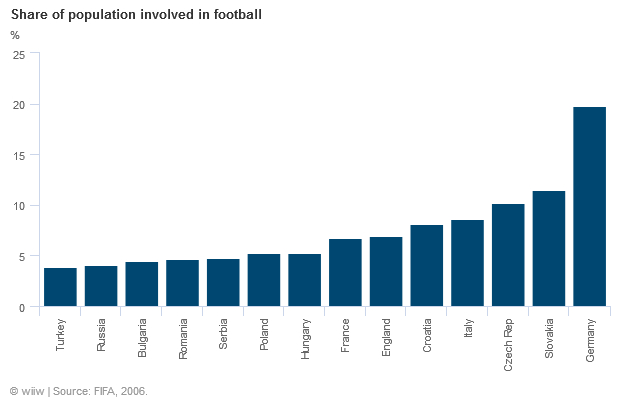

Variations in participation are surprisingly big between European countries, and may provide an important clue as to why some small nations punch above their weight. In 2006, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) conducted a survey of member associations (the 'Big Count') to gauge the level of participation in football. Although these data are now 12 years old, it is probably reasonable to assume that the numbers have not changed that much since the survey was conducted.

Across the world, 4.13% of the population were found to be involved in football. What is most interesting within Europe is that Germany stands out so much, with a participation rate of almost 20%. However, beyond that, two things are visible among CESEE countries. First, their participation rates are generally lower than in Western Europe. Second, three countries buck this trend: the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Croatia. Croatia’s participation rate was double that of Russia and Turkey, for example.

5. Openness to outside influence/innovation

The final explanatory variable in previous models of international footballing success is openness to outside innovation and ideas. A classic example of this is Barcelona in the 1980s who, following the death of Franco, signed the great Dutch player and (and later coach) Johan Cruyff. Cruyff had a huge influence on Barcelona’s way of playing, and his legacy included the great Barcelona team of 2009-11, which also had a decisive influence on the Spanish team that won three successive international titles in 2008-12.

This influence is generally difficult to quantify, and football has gone through a lot of phases. Often in the past, the CESEE region was itself a source of innovation. Hungary were viewed by many as the best team in the world in the 1950s, for example. Russia’s Viktor Maslov, as manager of Dynamo Kiev in the 1960s, played a key role in the development of the high pressing and zonal marking tactics currently so popular in contemporary elite European club football in Western Europe. Later, with the same team, Valeriy Lobanovskyi further developed the concept of high pressing.

What is clear, however, is that these days, as in much else in CESEE, football seems to rely chiefly on importing ideas from the West. The key players in most of the big CESEE teams play in Western Europe. This allows individual players exposure to elite coaching, and clearly brings some benefits for the national team (see also Branko Milanovic’s paper on football and globalisation here). However, it may not necessarily translate into a better performance overall for the national teams. In fact, this exposure of key players to Western leagues could have come at the expense of team cohesion.

One area where CESEE was particularly strong, at least under Communism (including in the teams of Maslov and Lobanovskyi), was in the functioning of the collective. Teams from CESEE were often physically better than their opponents, which is part of why some at least were successful at developing pressing. Pressing is a difficult tactic to perfect and, as well as high levels of fitness, relies heavily on players spending a lot of time on the training pitch together.

With CESEE players now scattered across Western Europe (and playing many different styles with their club teams), this is much more difficult than in the past, when the spine of CESEE national teams would often come from one club team in the region. This meant that the players were much more used to each other and their system. The importance of this can be seen in the World Cup victories of Spain in 2010 and Germany in 2014, both of which relied strongly on a core of players from one club with a defined system (Barcelona and Bayern Munich, respectively), and who trained together every day over full seasons.

Does Croatia’s appearance in the final signal a change of trend?

For a country of its size, Croatia’s success in footballing terms is extremely impressive. However, apart from Croatia, the story of CESEE’s footballing decline since around 1970 (and especially from the 1980s) is quite stark, reflecting a combination of smaller populations (owing primarily to state fracture) and in some cases relative GDP decline. A lack of new footballing ideas from within the region, and the reduction in the role of the state in supporting football, could also have played a role.

Interestingly, an active role for the state in sport, which was quite normal under Communism, appears to be coming back in at least part of the region. This is especially the case in countries with more authoritarian leaders, such as Russia, Turkey and Hungary (Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Viktor Orbán in particular are known to be keen football fans). However, this linking of the state and football works in a somewhat different way to the past, and so far, it looks like the Communists were much more successful at it than their successors (possibly not always by legal means, it must be said).

Unfortunately, Croatia’s success looks like an aberration in the regional trend, rather than the start of a positive new era. Even for Croatia, it will be very hard to repeat the heroics of 2018. The team is blessed with a “golden generation” which will not be around forever. Moreover, there is a big coin toss element to international football. Having beaten a strangely poor Argentina in the group stage, Croatia found themselves on the much weaker side of the draw, and reached the final without managing to beat any of the three (not very good) teams they had to play during 90 minutes. In the final against France, the first really strong team they had faced, they lost, conceding four goals in the process. Moreover, the country’s football federation is beset by scandal. And beyond Croatia, the picture is even more discouraging. Poland and Serbia were two of the few European teams not to make it out of their groups in 2018, while Russia’s performance in a World Cup in any other country would likely have been significantly worse.

As a result, the chances of teams from the region regularly repeating Croatia’s achievement of 2018 are quite slim. Although most will continue to converge with Western income levels, this process will slow over time. Even under the best case scenario, it will take decades for most to catch up with Western Europe. In addition, most countries in the region have small populations. Without a high football participation rate, like Croatia, this will continue to act as a major impediment to greater success.

Footnote

[1] In two world cups, 1930 and 1950, there were no quarter finals, while in another two (1974 and 1978) the quarter finals were replaced by a second round (in both cases featuring CESEE representatives).