Early election called in Turkey

19 April 2018

Macroeconomic imbalances that have built up in recent years are now likely to be reined in more quickly, but risks will remain high in the run up to polling.

- Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has called an early election for June 24th, more than a year earlier than scheduled. Afterwards Turkey will move to a presidential system.

- Very strong economic growth and rising popularity on the back of military operations in Syria increases the chances that Mr Erdoğan will win.

- Risks have been building for some time in economy, with stimulus measures enacted by the government contributing to the emergence of problematic macro imbalances.

- Should Mr Erdoğan win, we would expect his victory to be followed by tighter policy and attempt to rein in potentially destabilising imbalances.

- In the near term, macro stability will continue to depend on geopolitical risk perceptions and the pace of monetary tightening in the US.

The decision to call an early election is not much of a surprise. We had long noted the quite high chance of an early election being called, with the government likely to be keen to capitalise on current very strong economic growth. Interestingly, when calling the early election, Mr Erdoğan also referenced uncertainty in Syria and Iraq, which he argued made the June election necessary.

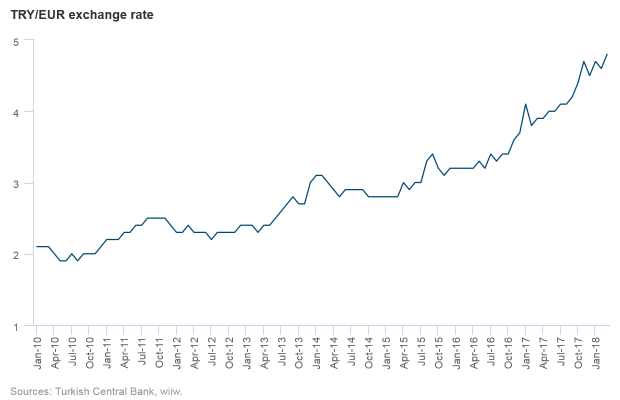

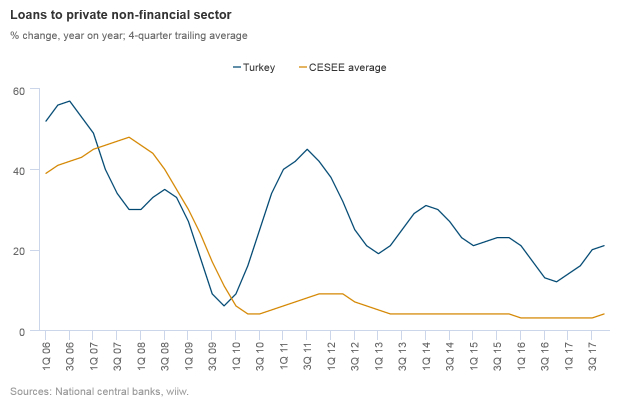

The economy grew by 7.4% last year, its best performance since 2013, but the authorities are aware that this cannot last indefinitely, not least because much of it is being driven by rising imbalances. The government has introduced fiscal stimulus, higher public investment, and a credit guarantee fund (CGF) to stimulate lending. Meanwhile interest rates have been kept low by the central bank. In combination with a weakening lira, this has pushed inflation into double digits. The fall in the value of the lira has created difficulties for corporates with FX-denominated debt. Two big business groups-- Ülker and Doğuş—recently submitted debt restructuring requests to creditors.

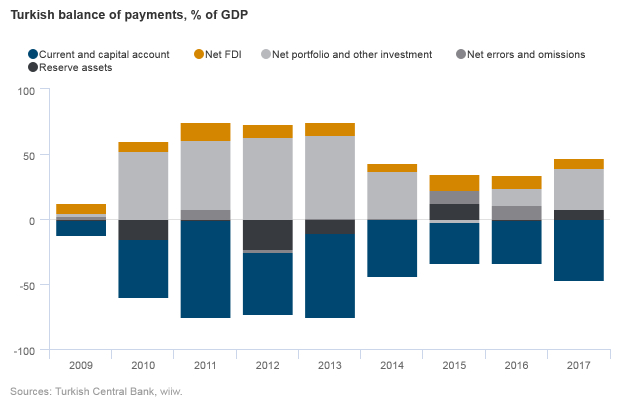

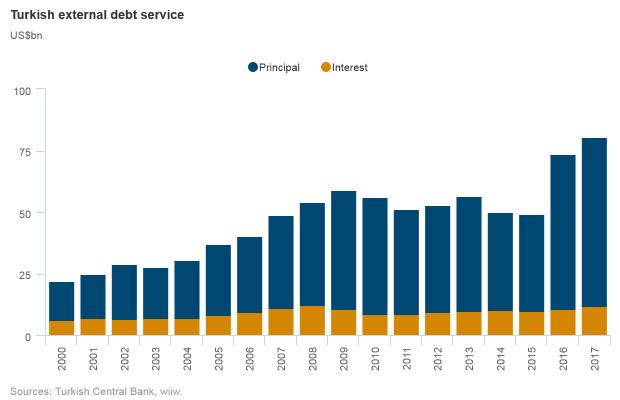

These polices have also contributed to a widening of the current account deficit, and a reliance on hot money inflows. External debt service payments in US dollars have shot up. Meanwhile credit growth has been very elevated for a long time, creating further risks for the financial sector (although currently non-performing loans are low as a share of the total, and banks are well capitalised). While at present the economy is clearly a political asset for the incumbent, the unbalanced nature of growth means that this is not guaranteed to last.

New system after election

Following the election, Turkey will move to presidential system, as determined by the constitutional referendum of 2017. The post of prime minister will be abolished, and parliament’s powers will be reduced. Mr Erdoğan and his party are keen to secure a larger mandate than they did in the 2017 referendum, where the vote was close and the major cities voted against it.

It is likely that Mr Erdoğan will win in June. However, opinion polls indicate that the level of support is not as strong as he may have hoped. Some polls have shown that an alliance of Mr Erdoğan’s AKP and its ally, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), could struggle to get to 50%. In general, Mr Erdoğan has been polling around 40%, quite far below the 51% he would need to take the presidency in the first round. However, Mr Erdoğan’s ratings have improved somewhat since he ordered military operations against Kurdish militias in northern Syria in January. A key question is whether Meral Aksener’s Good Party—which split off from the MHP last year—will be able to run (owing to the requirement that a party can only run if six months have passed since its first congress). If Ms Aksener can run for the presidency, this would split the nationalist vote, to the detriment of the AKP-MHP alliance’s share.

Macro implications: in near term economy remains vulnerable

With polls close, in the run up to the election the authorities may well continue to push the economy fairly hard, in the hope of further boosting support. Should Mr Erdoğan win the presidency, policy would then likely be tightened somewhat, in an attempt to rein in some of the macro imbalances that have built up in recent years. The market appears to expect this: immediately following the early election announcement, Turkish stocks and the lira rallied. Nevertheless, in the run up to polling, the Turkish economy will continue to face major risks. In particular, continued inflows of hot money fund the current account deficit will remain vulnerable to changing geopolitical risks perceptions and the pace of monetary tightening in the US.

Over the longer run, we do not view the current Turkish growth model as sustainable. A reliance on hot money inflows to fund a gaping current account deficit at a time of global monetary tightening brings clear risks. Turkey will either have to find a new growth model (for example based on attracting more FDI and rises in productivity), or get used to a much lower growth rate than has been the case recently.