Election outcome creates obstacles to 'hard' Brexit

14 June 2017

Uncertainty is even higher than before, but a truly 'soft' Brexit still looks very difficult to achieve. A commentary by Richard Grieveson.

- Following the general election on June 8th, forcing the the so-called 'hard Brexit' favoured by Prime Minister Theresa May and Conservative Party hardliners through parliament will be much more difficult.

- However, beyond that there is huge uncertainty. Neither the public nor the political class appears to be able to agree on what it wants. The Conservative Party will have a new leader before long. Political instability has risen even further, and new elections are a distinct possibility.

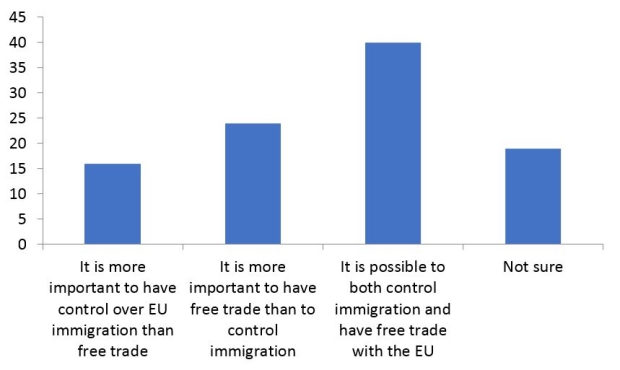

- A truly 'soft' Brexit still looks quite unlikely. Both main parties are committed to ending free movement, which suggests that the UK will still leave at least leave the Single Market. Remaining in the Customs Union for a transitional period is more likely than before, but in the long run it is difficult to see how the UK could accept having third-party trade deals negotiated on its behalf by the EU.

- Anyway, the UK will only have a limited say in what happens. Much, or most, depends on the EU27. Any 'emergency break' on EU immigration for the UK will likely have to be offset by significant restrictions on Single Market membership. Negotiations on the so-called 'divorce bill' to be paid by the UK and the Irish border have not become any easier.

- Economic weakness in the UK as a result of Brexit is starting to become apparent. This could shift public opinion and create space for politicians to do a 'softer' deal.

Trying to forecast British political developments in the last two years has been difficult. With a few exceptions, pundits, pollsters and forecasters en masse failed to predict an overall Conservative majority in 2015 and the vote to leave the EU in 2016. Last week’s general election was no exception. Even on the eve of the election, most pollsters expected the Conservative Party to increase its majority in the House of Parliament. Instead, it lost seats and is now facing the prospect of a minority government with support from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from Northern Ireland. British politics has become very unpredictable.

What the result tells us

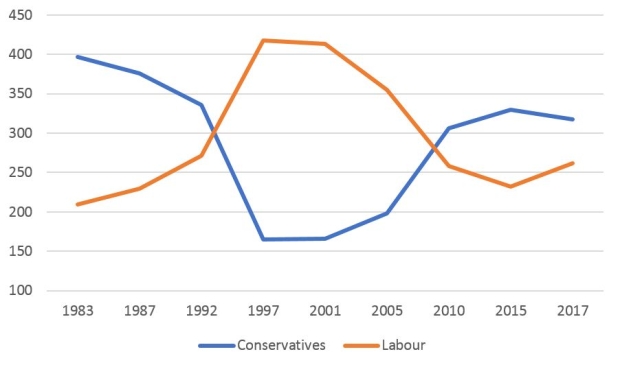

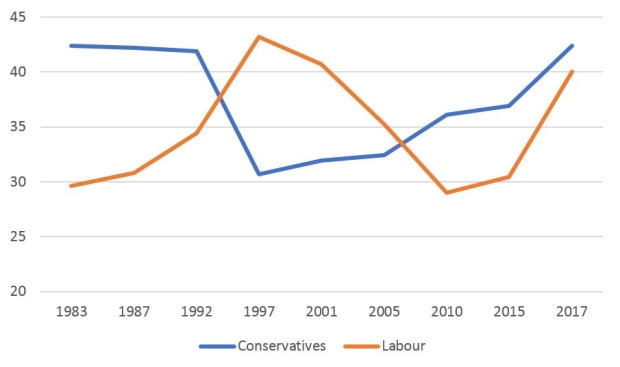

Having been written off by many (including the current author), the Labour Party increased their share of the vote on June 8th by the greatest margin since 1945. Their leader, Jeremy Corbyn, was highly successful in getting the young out to vote. However, the swing towards Labour from the Conservatives was not especially significant in the historical context, and celebrations in the Labour camp largely reflect initially low expectations. The party won 262 seats, higher than in 2010 and 2015, but far below the levels achieved by Tony Blair during his three election victories (including 418 in 1997). Labour is around 70 seats short of being able to govern on its own.

At first glance, the Conservative Party’s results were not a disaster. Its share of the vote reached 42.4%, the highest level for 34 years. Such are the vagaries of the UK’s first past the post electoral system that the Conservatives were still only 75 votes (out of over 32 million) in a few key constituencies from an overall majority(1). However, without an overall majority in parliament, and considering the initially very high expectations, the result was a huge disappointment for the party. The Conservatives started with a 20-point lead in the polls, but then campaigned disastrously. The so-called 'dementia tax' annoyed the base, while Prime Minister Theresa May had a particularly bad campaign.

A hard Brexit looks less likely now

Another election fairly soon is possible, but the Conservatives will be desperate to avoid this. They fear that they could lose this time. Moreover, this would first require a leadership contest (MPs would not allow Theresa May to lead them into another election). Conservative MPs want to avoid internal party conflict over the EU (something of a speciality of the party historically) that a leadership election would lead to. The internal party chaos and bloodletting after the Brexit referendum is fresh in their minds.

Dynamics within the Conservative Party and its DUP ally point towards a softer Brexit, for two reasons. First, there are at least 20-30 Conservative MPs against a hard Brexit, including the Scottish Conservatives (although their leader, Ruth Davidson, has so far couched her language on this). Second, the DUP themselves are a force for a softer Brexit. Although in favour of a UK exit from the EU, under pressure from local business leaders and sections of their base they have moderated their stance. In particular, the DUP are desperate to avoid a hard border with the Republic of Ireland, given the economic dislocation that this would cause.

If not hard Brexit, then what?

A truly 'soft' Brexit implies the UK staying in either the Customs Union or Single Market or both. In the case of the former, this would prevent the UK from negotiating separate trade deals with the rest of the world, something cherished by many Brexiteers. As for the Single Market, the UK would also have to commit to freedom of movement.

Current political reality indicates that staying in the Customs Union could be easier, at least as a transitory arrangement. It would be key to meeting DUP demands over the Irish border, and it appears to have some support among key Conservatives. Press reports indicate that some within the cabinet—including the Chancellor, Phillip Hammond—are pressuring Ms May to at least seek to extend the UK’s membership of the Customs Union. However, in the long run, it seems unfeasible that the UK could accept trade deals with the rest of the world being negotiated on its behalf by the EU.

Staying in the Single Market, however, looks much more difficult. Both Labour and the Conservatives want to end free movement, meaning effectively that parties committed to leaving the Single Market have an overwhelming majority in parliament. As a result, initial hopes in some quarters that the UK general election result could lead to a very different form of Brexit to that originally championed by Theresa May could be overdone.

Don’t forget the other 27

Such has been the insularity of the Brexit debate in the UK that the most important actor –the EU27—has often been forgotten. However, the bloc continues to hold most of the aces, and is largely in a position to dictate terms. In light of recent developments, and with the opportunity apparently there for a softer Brexit, the EU may be willing to pause the Article 50 process, offer an extension, or facilitate a move to EFTA membership as a holding strategy (in the current context completing negotiations by March 2019 looks even more unrealistic than it did before the UK election). The EU may also be willing to countenance some kind of emergency break on immigration into the UK as part of a soft Brexit deal (reports indicate that this was offered in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 Brexit vote).

However, whether this will materialise is a big question. While there may now be more hope on the EU27 side in light of Ms May’s failure to secure a majority in parliament for her hard Brexit course, there must also be exasperation with the UK, and concerns about the impact that continued uncertainty could do to the rest of the EU. The EU has many other priorities, and will now work on these on the assumption that the UK is leaving. As a result, the UK’s exit from the EU will be gradually formalised, even as negotiations are ongoing. Much will depend on the attitude of France and Germany. France’s new Prime Minister, Emmanuel Macron, wants deeper European integration. Having the traditionally obstructionist UK out of the way could be an advantage, particularly if its difficulties served as an encouragement to other EU members to accept more integration. Any concession from the EU27 to the UK on controlling immigration without significant restrictions on Single Market access in return is difficult to imagine.

Economic difficulties could create room for UK compromise

An additional factor that will increasingly become important is the state of the UK economy. Recent data indicate a marked slowdown in real GDP growth in Q1. Inflation is at a five year high, and real wages are falling.

Unsurprisingly, the uncertainty and risk of a rupture in trade arrangements is worrying businesses. A survey of UK business leaders by Harvard University found that almost all of those asked want to remain part of the single market and customs union. Another survey taken by the Institute of Directors in the immediate aftermath of the election found that 92% of respondents felt that uncertainty over the make-up of the next government was a concern for the UK economy. 86% saw a transitional deal with the EU as important.

Brexit risks compounding existing structural issues facing the UK economy, such as poor infrastructure (related to persistently low investment rates), low productivity, and high inequality. The current course is also dangerous for a country that relies on huge net FDI inflows every year to fund a current account deficit of 4-5% of GDP. FDI investors value political and regulatory stability, as well as the ability to freely trade with and hire staff from the rest of the EU.

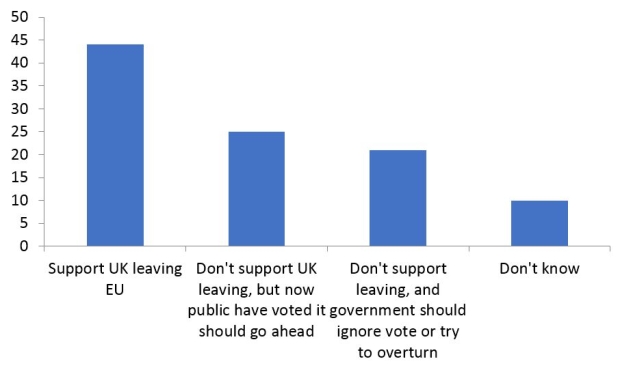

If the current slowdown in growth continues—and it probably will—it could change public opinion. So far, most UK voters—including many who voted against it—appear to have accepted Brexit. There is a chance, albeit quite a small one, that a material economic downturn could change this, potentially creating room for politicians to prioritise the economy over immigration, and paving the way for a softer Brexit stance.

Footnotes:

(1) On the other hand, around 1,000 votes less in certain constituencies would have meant that even with DUP support they wouldn’t have had enough seats to govern. Meanwhile, an extra 2,227 votes for Labour would have meant that a 'Progressive Alliance' coalition with the Liberal Democrats, SNP, Plaid Cymru, Green Party and one independent MP would have had a majority in parliament.

photo: Public Domain