Europe’s Choice: Power or Paralysis

15 January 2026

Instead of protecting its interests, the EU risks being squeezed between the geoeconomic power of the US and China. The absence of a true political, economic, and financial union holds Europe back

image credit: Nathan Murrell

This article was first published in European Voices magazine in December 2025.

The EU remains one of the world’s three great economic blocs, yet it often fails to translate its weight into geoeconomic influence. Dependencies in energy, security, and the digital economy leave it exposed. This affects not only Europe’s security but also its prosperity.

The global environment has changed dramatically in recent years. The current US administration has already upended many elements of the transatlantic alliance established over generations, while China and Russia are drawing closer, and the world is splitting into rival spheres. Caught between these two blocs, Europe risks becoming squeezed in the middle. The EU must now decide whether it wants to shape the emerging order and, in doing so, ensure its own future economic prosperity, or to passively adapt to decisions made elsewhere and risk long-term economic decline.

Retreat and Fragmentation

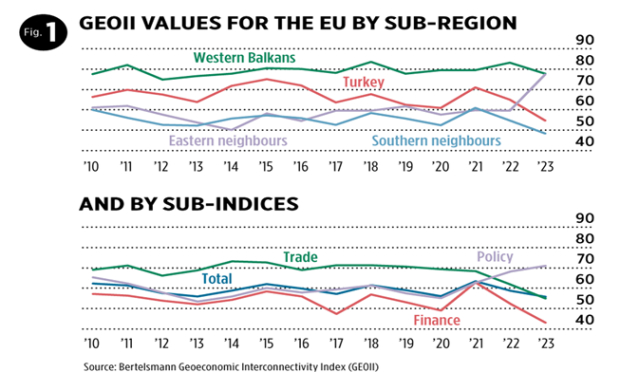

Even in its near vicinity, the EU is losing ground. The recently published Bertelsmann Geoeconomic Interconnectivity Index (Figure 1) shows that while the EU remains the main economic partner for most neighbouring states, China has rapidly expanded its footprint, and Russia retains leverage through energy and raw materials. And even where the EU is doing better, in the policy domain, this often does not translate into deeper economic integration or political alignment. Serbia, for example, has strengthened institutional links with Brussels while simultaneously tightening economic connections with both Moscow and Beijing.

wiiw’s Autumn Forecast Report shows these shifts already harming Europe’s economy, especially in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Manufacturing-heavy economies in the region face rising costs, disrupted supply chains, and reduced foreign investment. Labour costs have risen sharply in recent years, far ahead of productivity growth (Figure 2). Dependence on external energy, technology, and defence inputs leaves Europe vulnerable to coercion. Fragmentation is visible in weakening competitiveness, productivity and growth.

Europe’s embrace of globalisation delivered prosperity but also structural vulnerabilities. The first is energy dependence. Despite the rapid diversification away from Russian supplies, Europe still relies heavily on imported fossil fuels. Energy-intensive industries continue to face structurally higher costs than before the war. Europe’s green transition will eventually reduce exposure, but the benefits will take time to be fully felt.

Digital Dependence

The second is digital dependence. Europe’s cloud infrastructure, AI capacity, and semiconductor supply chains are overwhelmingly controlled by non-European firms. More than 70 per cent of cloud services used in the EU come from three US providers. This leaves European firms vulnerable to extraterritorial regulation, limits data security, and constrains the EU’s ability to scale its own digital industries.

The third vulnerability is defence-industrial dependence. The war in Ukraine has exposed the limits of Europe’s defence capabilities: key components of ammunition, electronics, and propulsion systems are still sourced from outside the EU, and production capacity is fragmented across national lines. This weakens Europe’s strategic autonomy and limits the economic benefits that coordinated defence investment could generate, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. Together, these dependencies show that Europe’s openness — once a source of strength — now amplifies vulnerability rather than power.

The Power We Don’t Use

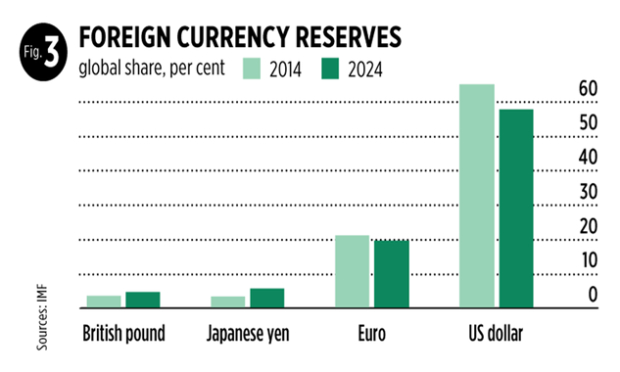

Despite these weaknesses, Europe retains formidable strengths. It remains a regulatory superpower: the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act have already reshaped global tech behaviour, as major US and Chinese platforms adapt to comply. Europe also leads in green technology and energy efficiency, with the highest share of renewable electricity among major economies. It hosts one of the world’s densest clusters of advanced manufacturing, remains the largest global trading bloc. The euro is also the second most important reserve currency, giving the EU leverage that it rarely uses, unlike the US with the dollar (Figure 3). Europe excels in science, research output, and human capital, supported by strong education and quality of life. In short, Europe has the capabilities of a geoeconomic power — but rarely deploys them strategically.

The EU already has a broad toolkit — trade policy, sanctions, investment screening, export controls, and anti-coercion measures. However, these instruments remain reactive, fragmented, and underused. While the EU is an economic and financial bloc that is fully comparable with the US and China in terms of size, it faces much more severe difficulties in mobilising these resources quickly and in a decisive way. The much-quoted Draghi report underscores the need for scale and coordination: completing the single market, pooling investment, expanding EU-level fiscal capacity, and mobilising private capital.

There are at least three big reasons why the EU struggles to act. Fragmented decision-making creates numerous veto points. This is not only about populists; it is also about the reluctance of key member states to confront strategic realities. The EU’s political economy encourages caution: German industry’s reliance on China, or southern Europe’s distance from the Russian threat, weakens common resolve. And many elites cling to a rules-based worldview even as rivals pursue power politics. The EU still too often indulges in wishful thinking, preferring to imagine the world as it would like it to be, and struggling to engage with the world as it is.

Learning by Doing

Yet the EU can act decisively. The historian Luuk van Middelaar describes Europe’s awakening to the “rule of events”: moments when history forces political, not procedural, action. The COVID recovery fund and 2022 sanctions on Russia proved this. The sanctions were costly for powerful interest groups within the EU, but showed that, under sufficient pressure, the bloc can act collectively. They provide perhaps the best example of decisive EU action to address a geopolitical challenge with strong geoeconomic measures.

First, sequencing and a gradual approach were important. The European Commission and the diplomatic service EEAS broke the sanctions into packages — each focused on areas where consensus was achievable at that moment. Second, the EU allowed carve-outs and exemptions where it did not dilute the overall impact, for example, allowing Hungary and Slovakia to continue to import Russian oil. Third, the EU leveraged moral pressure. The unprovoked invasion and its accompanying horrors made it hard for the more cautious countries to be seen to be blocking action in response. Especially at the start, public opinion in Europe was overwhelmingly pro-Ukraine. The EU’s response was framed as based on European values, not just interests. Even Hungary never wanted to stand alone indefinitely. Once it extracted concessions and the political costs of isolation grew, it signed on. Fourth, the EU acted together with other democracies around the world. This allowed the EU to benefit from the input of countries that are more comfortable with realpolitik, and supported the framing of the response as being about the defence of values.

“Strategic sobriety, not nostalgia, is now the precondition for Europe’s security and prosperity.”

The EU clearly did not get everything right. And it must also be admitted that the EU’s 2022 response relied very heavily on coordination with and support from the US, something that cannot be guaranteed under the current administrations. In a way, this is the EU’s greatest strategic dilemma of all: how to plan for a world where the US support that generations of (especially Western) Europeans have taken for granted may no longer exist in the same way.

From Crisis Reflex to Action

The EU has shown that it can act decisively in a crisis. The task now is to turn this crisis reflex into a permanent, coherent geoeconomic strategy — one that identifies Europe’s interests early, defends them consistently, and does not wait for a catastrophe to summon its courage. Here things are moving, for example, with increased defence spending, but too slowly.

A clearer embrace of geopolitics is required. As French President Emmanuel Macron has argued, Europe must learn to speak the language of power, shed its complacency, and accept the world as it is. That means confronting uncomfortable realities: that partners can be unreliable, rivals exploit economic leverage, and neutrality in an age of coercion is an illusion. Strategic sobriety, not nostalgia, is now the precondition for Europe’s security and prosperity.

But Europe will only be confident abroad if it is confident in its power at home. The EU often underestimates its own assets — its regulatory strength, industrial capacity, scientific excellence, and the gravitational pull of its single market. Gaps remain: meaningful strategic autonomy requires greater fiscal integration, deeper capital markets, and a willingness to mobilise public and private investment at scale.

Ultimately, however, coherence requires legitimacy. Critics like the historian Perry Anderson are right that the EU was not designed to project power but was built to contain it. But that design is not destiny. If Europe is to act consistently rather than episodically, it must close the distance between its institutions and its citizens. This means being braver with voters —explaining why geoeconomics matters for jobs, prices, security, and the European way of life — and involving them more directly in shaping the choices ahead. Ideas like transnational assemblies, participatory budgeting, and a genuinely European electoral space all deserve consideration.

Europe does not lack power; it lacks the habit of using it. The choice now is to turn crisis improvisation into lasting purpose. What is needed is the confidence to act, deliberately and consistently, in a world that will no longer wait for Europe to make up its mind.

is deputy director at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), teaches economic history at the University of Vienna, and is a member of the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group (BiEPAG). He coordinates wiiw’s analysis and forecasting of Central, East, and Southeast Europe.