Europe’s Economic Dependencies Demand Pragmatic Solutions

13 December 2024

Instead of ideologically motivated economic policy, Europe needs a pragmatic approach to up its competitiveness. The answer is a Catalytic Industrial Policy to energise the green, digital, and social sectors

image credit: wiiw/Hans Schubert

This article was first published in European Voices in September 2024.

Secure energy supply at a moderate price has been the basis of modern economic growth since the onset of the Industrial Revolution. As long as these conditions are met, businesses, governments, and society will not be too bothered about sources and availability, often for several decades. However, in times of war, the economic dependency on energy supply becomes a matter of national interest. For Europe, this moment occurred at the latest in the months before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when Russia leveraged Europe’s dependency on gas imports by reducing supply and thus increasing prices. This was exacerbated by Germany’s exit from nuclear and coal-powered electricity production without comparable replacement by new capacities in green energy. As Russia deliberately risked terminating its long-term energy union with Europe, the latter became open to blackmail.

In hindsight, increasing energy import dependency after the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war in 2014 with the Russian occupation of Crimea was a bad idea. However, most European economies did exactly this (Figure 1). Core European economies, such as Germany, Austria, Italy, and the Netherlands, raised their overall energy import dependency between 2013 and 2022 to levels around 70 to 80 per cent of gross available energy, neglecting the development of green energy infrastructure. Only a few countries, typically closer to Russia, such as the Baltic states, Finland, Sweden, and Turkey, have been more sensitive to Russian imperial expansion. They reduced their overall energy import dependency over the same period, to levels of about 30 to 70 per cent.

“From 2013 to 2023, the vast majority of European economies increased their export share by double digits.”

Apart from being energy-intensive, modern economic growth also implies an advanced division of labour and international trade. The trade openness of Europe’s economies is among the highest in the world. In 2023, the majority had shares of exports of goods and services in per cent of GDP far above 50 per cent (Figure 2). While the advent of a new Cold War started a long time ago and related trade barriers are on the rise, Europe has by and large continued to increase its export exposure. From 2013 to 2023, the vast majority of European economies increased their export share by double digits. However, some have experienced a slight decline. The Central European factory economies that are part of the German automotive cluster, such as Czechia, Hungary, and Slovakia, had particularly declining export shares even while remaining at 70 to 90 per cent of GDP by 2023.

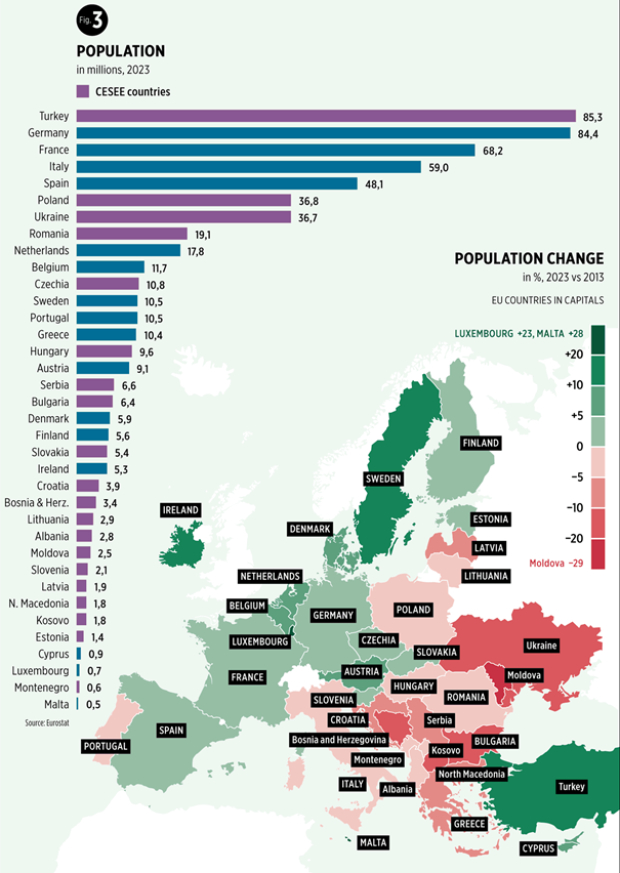

In simple models, long-term economic growth can be explained by the dynamics of labour, capital, and technological input. The European integration process involved strong centripetal movements of labour from poor to rich regions and capital and technology in the reverse direction. As a consequence, the population of the wealthier parts of Europe grew over the last decade at rates of 5 to 10 per cent (Figure 3). Given the massive ageing process in Europe, dependency on the influx of young families is strong and even slight population growth does not necessarily help to fully overcome the labour shortages that come with demographic decline. Thus, the situation in depopulating societies is much worse. By and large, Central, East and Southeast Europe lost up to 10 per cent of their population between 2013 and 2023. This comes on top of earlier waves of mass emigration to the west and north of Europe during the 2000s. While most European societies are small by international standards, countries in Central, East, and Southeast Europe are even small by European standards. This also implies tiny domestic markets, an increasing dependency on access to larger export markets, and the subsequent need to specialise.

Population in millions, 2023

Lack of labour is aggravated by a lack of capital and access to technology. Foreign direct investment provides for both and enters to a large extent in export-oriented sectors, hence creating the basis for reaching out to global markets. Stocks of FDI are fairly high throughout Europe, reaching between a third and two-thirds of GDP (Figure 4). However, since the global financial crisis, the dynamics of FDI have been quite sluggish. Investment destinations that have lost FDI relative to their GDP between 2013 and 2022 comprise countries that had an earlier large influx of FDI in the real estate sector or experienced recent periods of political instability, most of them located in Central, East, and Southeast Europe.

To summarise, many economies particularly from Central, East, and Southeast Europe have small and falling population numbers. This is increasing their dependency on substituting labour with capital and technology inputs. This, in turn, is required to meet the increasing needs of export dependency due to tiny home markets. At the same time, the region has to reduce its energy import dependency as the new Cold War is causing major disruptions in energy security, which involves high substitution costs. Governments of the region have chosen different policies to tackle these massive challenges. The EU and Germany and France, its leading member states, as well as Russia, China, and the United States have exerted influence on the region of Central, East, and Southeast Europe.

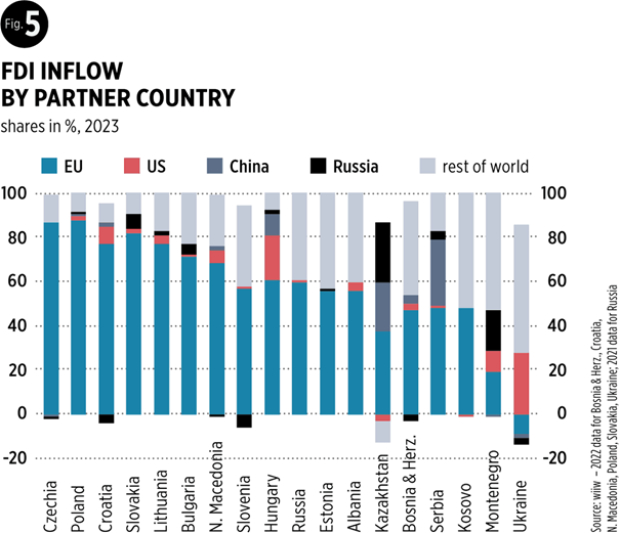

“At least in terms of FDI stocks, the EU is still (almost) the only game in town.. . . The United States plays only a minor role.”

So far, at least in terms of FDI stocks, the EU is still (almost) the only game in town. With very few exceptions, between 50 and 90 per cent of all FDI stocks were originating from EU member states by 2023. The United States plays only a minor role in controlling foreign direct investment in the region with the notable exception of Kazakhstan. China’s FDI shares are even smaller. Only in Serbia, do Chinese companies control more than 10 per cent of the FDI stocks. Russia also has only minor stakes in the region, with the exceptions of Montenegro, Moldova, and Belarus, where it holds between 10 and 30 per cent of the FDI stocks.

Looking at the most recent FDI inflows, the picture is a bit more diverse but not fundamentally different. Again, for almost all countries for which data is available, the EU is the country of origin for 50 to 90 per cent of all FDI inflows in 2023 (Figure 5). Ukraine is an exception. Here, FDI from EU member states was disinvested while almost 40 per cent of FDI inflows originated from the United States. Another substantial engagement of US FDI in 2023 was in Hungary, where it had a share of 20 per cent in total FDI inflows. Major Chinese FDI targets in 2023 were Serbia and Kazakhstan with a share of 30 per cent in total FDI inflows, as well as Hungary with almost 10 per cent. Among others, major recent Chinese investments in the e-vehicle, battery, and IT sectors of the region were recorded. Russian FDI inflows were strongest in Montenegro and Kazakhstan, with almost 20 and 40 per cent of total inflows, respectively.

FDI inflow by partner country

In terms of regional FDI stocks, EU shares on average make up almost 70 per cent of the totals but in recent FDI inflows in the region, this share is at less than 60 percent. It might be still too early to draw strong conclusions from short-run trends. However, given the weak economic performance in core EU economies, a further deterioration of the EU’s position in FDI ownership in Central, East, and Southeast Europe can be expected. Foreign powers such as China will likely take advantage of regional investment opportunities and will thereby promote their newly established dominance in selected high-tech sectors.

Changing patterns of FDI ownership will also have their impact on subsequent trade flows. So far, China, and to a lesser extent also Russia, already have some control but not dominance over some of the region’s imports. The exceptions are Belarus and Kazakhstan, where import shares of China and Russia were substantially higher than those from EU Member States in 2023. Otherwise, in most of the other countries from Central, East, and Southeast Europe, we observe EU import shares ranging from about 45 to 85 per cent of total imports. Chinese import shares hover around 5 to 15 per cent. Imports from Russia are typically below 5 per cent of total imports, even in Russophile countries such as Serbia.

“Any major disruptions in the Central European automotive cluster have the potential for high-risk impact.”

In terms of export destinations, the EU member states still dominate. This is also the case for the origin of FDI stocks. Both are strongly correlated due to the strong bias toward export-oriented FDI companies. Average EU export shares in the region typically range from about 60 to 80 per cent. Only a few regional economies’ exports are targeted towards China, Russia, or the United States, for that matter. Thus, so far, Central, East, and Southeast Europe have little dependence on extra-EU markets. Nevertheless, with slowly changing FDI patterns, exports might change destinations over the longer run.

Moreover, structural changes in the automotive sector, as well as massive subsidies by the United States and China in their green and digital industries, have the potential to make substantial parts of the region’s export sectors obsolete and outperformed by US and Chinese competitors. To grasp the potential vulnerability of the region’s economies, it is worthwhile to look at the share of vehicle exports in total exports (Figure 6). EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe in particular have vehicle export shares of as much as 10 to 20 percent, comparable to those of Austria and Germany. In Slovakia, this share is even at above one-third of all exports. Any major disruptions in the Central European automotive cluster have the potential for high-risk impact.

Thus, what are the possible scenarios for the future development of Europe in general and Central, East, and Southeast Europe in particular? One potential outcome of a lacklustre response to the overwhelming challenges in the areas of green and technological transition as well as the democratic legitimation of structural change is a further dismantling of liberal democracy and a reversal of the European integration process. Several trends and political ruptures such as Brexit, rising authoritarianism as well as political polarisation point, in this direction. Moreover, a self-mutilating “debt-break-austerity” in Germany, Europe’s core economy, is leading to further degradation of vital strategic infrastructure and a vicious cycle of beggar- thy-neighbour policies on the continent.

A divided Europe of competing nation-states will be a playground for foreign powers exercising their influence. A further proliferation of armed conflicts on European soil will become more likely. Unresolved constitutional issues in the Western Balkans could be misused as a potential casus belli. A slow process of deindustrialisation will lead to less and less globally competitive European enterprises due to a lack of coordination in research and development, capital provision, public procurement, and targeted investment. Some countries will remain factory economies specialised in the lowest industrial segments of the global value chain. Others will further specialise in low-tech services such as tourism. A third group will refocus on exploiting the primary sector of the economy, extracting and producing raw materials such as farming, fishing, forestry, and mining. Countries from Central, East, and Southeast Europe would be particularly vulnerable given their often weak institutional background and modest financial, physical, and human capital stock.

A Europe that does not cooperate and is thus not able to manage the green and technological transition with the support of broad segments of society will also likely have lower levels of productivity relative to the rest of the world. Assuming an annual nominal GDP per capita growth differential of one per cent vis-à-vis the United States, two per cent vis-à-vis Russia, and three per cent vis-à-vis China, China’s nominal GDP per capita will overtake EU levels by 2065 and Russia by 2080. At the same time, the US will have a four times larger GDP per capita, compared to the EU, up from a current ratio of two, according to the International Monetary Fund. These ratios can change even over shorter periods quite dramatically. At the outbreak of the global financial crisis, the nominal GDP per capita of the US and the EU were almost at parity.

“It is high time to learn from industrial policy experimentation and leave the laissez faire concept behind.”

To avoid a bad equilibrium and move to a better one, the EU and its members need to step up cooperation substantially. Instead of ideologically motivated economic policy, such as the “debt-break” stance, we need a pragmatic approach that takes into consideration the political economy of structural change. Past policies intended to foster the EU’s internal market without a long-term strategic industrial policy were aimed primarily at raising efficiency and improving competitiveness among EU members. They thereby neglected the trade-off with security in its broadest definition (including social, energy, military, and other types of security) and the interplay with an electorate that (more often than not) lives in “places that don’t matter” and that has been exposed to a succession of massive crises.

There is a need for a Catalytic Industrial Policy aimed at simultaneously maximising positive outcomes on the green, the digital, and the social axes – to speed up their realisation. Respective investments need to be guided in the desired directions, while ensuring that the benefits of a Catalytic Industrial Policy are widely shared, for example through conditionalities. Procurement and funding could be made conditional on, for instance, greener supply chains, profit sharing, the reinvestment of profits (stipulating the level, the geographical localisation or the type of reinvestment), or better working conditions. The direction of innovation and economic activity could also be influenced, leading to socially and environmentally desirable technologies. All of this has to be seen in the context of a shift towards longer-term, public-value- oriented economic thinking. The US CHIPS and Science Act is agood example of a state-directed industrial upgrade via grants, tax credits, and, more importantly, disciplining measures such as construction and operational milestones, prior due diligence, upside sharing agreements for potential future profits, the activation of private capital and restraints on share buybacks. It should be clear that the time when political decision-making seeks mainly to minimise potential failure (and hence typically does not act at all) is over. It is high time to learn from industrial policy experimentation and leave the laissez-faire concept behind.

At an intellectual level, the paradigmatic shift has already occurred, and “big thinking” is no longer regarded as naive. Understanding the bigger picture should also be the guiding principle when it comes to issues of European integration. To keep foreign powers out of European internal affairs, the EU accession of the Western Balkans, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia should be stepped up. EU enlargement was always primarily politically motivated. In addition to a NATO membership, it offers further elements of security, particularly in the economic sphere with its access to a huge market. In parallel, the decision-making process of the European Union institutions needs to be reformed. The Union needs to be ready to finally understand its economic dependencies, tackle the related challenges, and find appropriate and pragmatic solutions as soon as possible.

While such a scenario would be likely beneficial to all of Europe, it is particularly Central, East, and Southeast Europe that would gain. More prosperity and security in the region could help to reverse the ongoing demographic decline by attracting young families as well as high-tech foreign direct investment. Catalytic Industrial Policy measures could also help the region to reduce its energy import dependency via investment in green energy projects and infrastructure. Coordinated investment, also in “places that don’t matter,” could have the potential to stop the degradation of liberal democracy and make the gains from access to the EU’s single market appreciable throughout Europe.