Evidence of brain gain for some Western Balkan countries

11 March 2021

A new study shows net inflows of young, educated people into Serbia, Montenegro and North Macedonia since 2010.

by Sandra Leitner

photo credit: iStock.com/fcscafeine

wiiw has just published a detailed study, commissioned by the European Training Foundation (ETF), which develops the ‘cohort approach’ to estimate the extent and the skill composition of net migration – the difference between immigration and emigration ‒ in the six Western Balkan countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia) between 2010 and 2019. To account for the importance of vocational education and training in the region, the study differentiates between four educational levels: Low (primary or lower secondary education), Med-GEN (medium-general – upper secondary general education), Med-VET (medium-VET ‒ upper secondary vocational education and training), and High (tertiary education).

The main findings are as follows.

- During the period of analysis all six Western Balkan countries experience net emigration. However, the extent of these movements differs across countries.

- The young are the most mobile and the most likely to emigrate.

- A further breakdown by the highest level of education shows that net emigration occurs mainly among the medium- and low-educated.

- Net migration flows among the highly educated are generally lower but more differentiated across the Western Balkan countries, with evidence of brain drain in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo but brain gain in Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

- The international mobility of local and foreign students is a key driving force behind the extent of the brain drain or brain gain found in the six countries surveyed.

The Western Balkans continue to be a region of net emigration

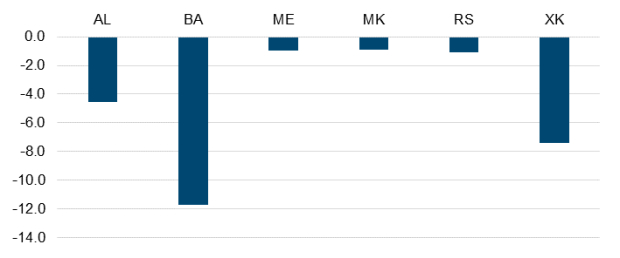

For economic and political reasons, the Western Balkan countries have traditionally been emigration countries. Our results show that this continues to be the case: between 2010 and 2019 all six countries of the region experienced net emigration. However, the extent of net emigration differs across countries and is highest in Bosnia and Herzegovina, followed by Kosovo and Albania; it is lowest in Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia (Figure 1). Important drivers behind these non-negligible net emigration flows are pervasive poverty (as in the case of Kosovo), extensive diaspora networks, a relatively high unemployment rate, more (and higher-quality and better-paying) employment options abroad, or particular schemes which facilitate migration, such as Germany’s Western Balkan Regulation.

Figure 1: Average net migration rates between 2010 and 2019 (per 1,000 people)

Note: The average net migration rate is the average of the ratio between net migration (as the difference between immigration and emigration) and mid-year population over 2010-2019.

Sources: Labour force surveys for Albania (AL), Bosnia and Herzegovina (BA), Montenegro (ME), North Macedonia (MK), Serbia (RS), and Kosovo (XK); own calculations.

The young are the most likely to emigrate

We find that net emigration is particularly high among the young, which can be explained as follows. First, the young face particularly high unemployment rates – in fact, they are two to three times more likely to be unemployed than their older peers. Second, many young people leave to join their families, especially those aged 19 years or younger. Third, many young people emigrate to pursue further education abroad, particularly those in their early to mid-20s who have finished their upper secondary education, typically between the ages of 18 and 19. Importantly, apart from the EU28, Serbia has become an important regional hub and attracts many foreign students to its universities. Finally, while young people have a higher propensity for risk-taking behaviour, they are also more likely to have fewer responsibilities, such as looking after family members, and they are more willing to embark on new professional career paths ‒ all of which makes them generally more prone to migrate.

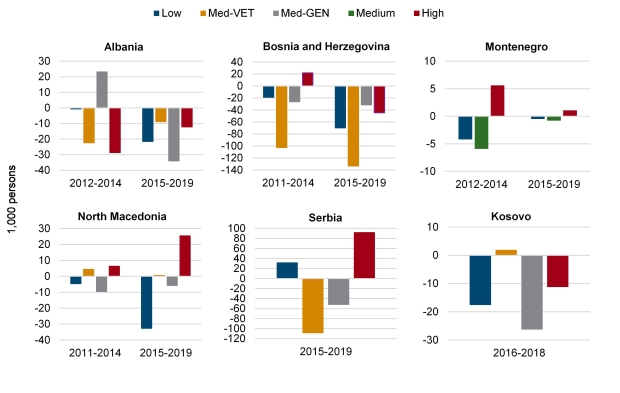

Net emigration from the region mainly occurs among the medium- and low-educated

Except for Albania, net emigration occurs mainly among the medium- and low-educated, with some cross-country differences regarding their relative importance (Figure 2). In Bosnia and Herzegovina net emigration is most pronounced among persons with Med-VET skills. In Kosovo it occurs mainly among persons with Med-GEN as their highest level of education, while in Montenegro net emigration is also mainly among the medium-educated. In North Macedonia net migration mainly occurs among the low-educated. In Serbia net emigration is solely among the medium-educated but is particularly high among those with Med-VET skills. By contrast, in Albania net emigration is highest among the highly educated.

Figure 2: Cumulative net migration flows by level of education: 2011-2019

Note: The different periods of analysis for particular countries are due to different substantial breaks in the underlying data. Negative numbers refer to net emigration, while positive numbers refer to net immigration. The ISCED break in the Montenegrin LFS data between 2013 and 2014 strongly affects how the two groups of Med-VETs and Med-GENs are classified. To facilitate interpretation, net migration flows for both periods are calculated for the aggregate Medium group as the sum of net migration flows of Med-VETs and Med-GENs.

Sources: Labour force surveys for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Kosovo; own calculations.

There is evidence of brain drain in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, mainly among recent university graduates

There is evidence of net emigration among the highly educated – and therefore evidence of brain drain – in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Brain drain is substantial in Albania, where the highly educated account for around 40% of the total cumulative outflow in the period analysed, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, where they account for 6% of the total cumulative outflow in the period analysed. Net emigration of the highly educated in Kosovo is also sizeable but lower than that of the group of Med-GENs and the low-educated.

In Albania and Kosovo, brain drain is particularly high among those in their early to mid-20s, which suggests that the majority leave just a few years after graduating from tertiary education.

By contrast, there is evidence of brain gain in Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, especially among young university graduates

Our analysis finds net immigration of the highly educated – and therefore brain gain – in Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia (Figure 2), which is generally highest among those in their 20s. Since this is also the age at which tertiary education is typically completed, our results suggest that net immigration of the highly educated is mainly driven by students who return to their home countries after graduating from tertiary education abroad. At the same time, we also observe a high net emigration among both Med-VETs and Med-GENs in the youngest cohort, which is consistent with the theory that both groups leave in larger numbers after graduating from upper secondary education and return as university graduates when they are still in their 20s. In the case of Serbia brain gain is also associated with foreign students attending Serbian universities, which record an increase in the number of foreign students who come mainly from neighbouring countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro.

Furthermore, in Serbia and Montenegro net immigration of the highly educated is also associated with the immigration of highly skilled workers who are attracted to work there, in addition to education.

Policy initiatives must be geared towards the young and the highly educated

Governments in the region need to step up their efforts to reduce the youth unemployment rate – which is the highest in the world – and to create quality and fairly paid jobs for the young, many of whom are engaged in temporary jobs, often in the informal economy, in order to assure them of a decent living in their home countries and make emigration less attractive.

Brain drain is also related to poor employment opportunities for the highly educated. In many fields of study there is an oversupply of graduates, who then have difficulties in finding a suitable job. Or there is a mismatch between the skills needed in the labour market and the skills acquired at university. Hence, higher education policies need to be better aligned with and more focused on labour market needs with, for instance, closer cooperation between higher education institutions and employers or specific scholarship programmes that help to steer students towards priority subjects.

Finally, those countries which experience brain gain should have policies in place which guarantee that the imported foreign knowledge and know-how benefit their local economies.

Related Projects

Related Publications

- Net Migration and its Skill Composition in the Western Balkan Countries between 2010 and 2019: Results from a Cohort Approach Analysis

- Net Migration and its Skill Composition in the Western Balkan Countries between 2010 and 2019: Results from a Cohort Approach

- A Skill-specific Dynamic Labour Supply and Labour Demand Framework: A Scenario Analysis for the Western Balkan Countries to 2030