First Expanded BRICS Summit a Potemkin Village?

30 October 2024

Russian President Putin scored major PR points by hosting the first expanded BRICS summit. However, to date, BRICS membership has shown no measurable economic impact

image credit: istock.com/Andrea Nicolini

The first expanded summit of the BRICS Plus club from 22 to 24 October 2024 was a notable PR achievement for Russia. As well as hosting the leaders of the world’s two most populous countries – China and India – President Putin also welcomed the leaders of Brazil and South Africa, and, for the first time, of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates, which joined the BRICS Plus club a year earlier. Additionally, 13 countries have been added as BRICS partner nations: Algeria, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Uzbekistan and Vietnam.

In Kazan, the capital of Russia’s Muslim-majority Republic of Tatarstan on the Volga River, representatives from these nations gathered alongside other political leaders, including even Milorad Dodik, President of the Bosnian Serb entity Republika Srpska. The presence of UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan, who leads NATO member Turkey and has expressed interest in joining BRICS, lent the event even greater significance.

The fear of Western sanctions is a strong motivator for many countries – particularly authoritarian regimes – to join the BRICS Plus club. As a result, key topics at the summit included the development of new payment and trade mechanisms to bypass Western-dominated systems. However, the final communiqué was heavy on rhetoric, but light on specifics regarding these critical issues.

Overall, the short- to medium-term prospects of the BRICS Plus club significantly altering the world order remain limited. An analysis of the Research Centre International Economics (FIW) from early 2024 found that the political and economic interests of this diverse group of countries are too varied to pose any serious challenge to Western dominance. However, as a bloc, their substantial energy reserves could give them leverage over the West.

From China’s perspective, BRICS Plus could, at the very least, unsettle the US and its allies, while bolstering some bilateral relationships, particularly in the Middle East, where China seeks greater influence. Meanwhile, the BRICS Plus initiative provides smaller powers with an opportunity to position themselves as players in the geopolitical rivalry of a budding Cold War 2.0 between China and the US, allowing them to avoid becoming mere pawns or battlegrounds in the conflict.

Ending the US dollar’s role as the global reserve currency remains an ambitious goal for Beijing and Moscow, but it is unlikely to be achieved in the foreseeable future. As the world’s largest economy and sole military superpower, the US still holds significant global influence, with almost 60% of international currency reserves held in US dollars, compared to just about 2% in Chinese yuan, as of Q2 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The BRICS group’s track record further suggests that a rapid end to the Pax Americana is unlikely.

The bloc’s most notable achievement thus far has been to establish the New Development Bank, modelled on the World Bank. Since its inception in 2014, the bank has issued loans totalling just over $30bn, most of which have been issued in US dollars. This underscores the fact that while some major countries are dissatisfied with post-Second World War institutions and with their own limited influence in global decision making, the US dollar remains firmly entrenched in the global financial system.

Let us take a look at the economic track record of the BRICS countries since the group’s establishment in 2006. The original members – Brazil, Russia, India and China – were joined in 2010 by South Africa. These economies differ significantly in both their level of economic development and their sectoral structures. Furthermore, the BRICS bloc has yet to establish any specific set of institutions or create mechanisms for significant financial reallocation through major fund transfers.

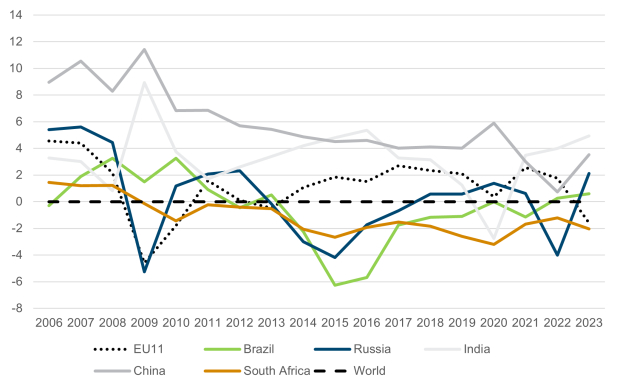

As a result, the BRICS economies have followed distinctly different development paths. In terms of growth of real GDP per capita, China and India have outperformed the global average (Figure 1). However, the smaller members – Brazil, Russia and South Africa – have generally seen growth rates running at below the world average. By contrast, the 11 Eastern European countries that joined the European Union at around the time the BRICS group was formed (EU accession dates 2004, 2007 and 2013) have, overall, experienced rates of growth of GDP per capita that have generally been above the global average.

Figure 1 - Deviations from global real GDP per capita annual growth rates, in percentage points

What drives economic growth? Initial levels of economic development play a key role in growth rates, with lower-income countries typically experiencing more rapid growth than higher-income ones, thanks to their capacity to adopt advanced technologies and business practices from more developed economies. Economies that invest heavily in both physical and human capital also tend to grow more quickly. Additionally, membership of trade blocs provides important market access, fosters specialisation and facilitates integration into global value chains. Finally, as research by recent Nobel laureates Daron Acemoğlu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson highlights, robust institutions are critical for sustained long-term economic development.

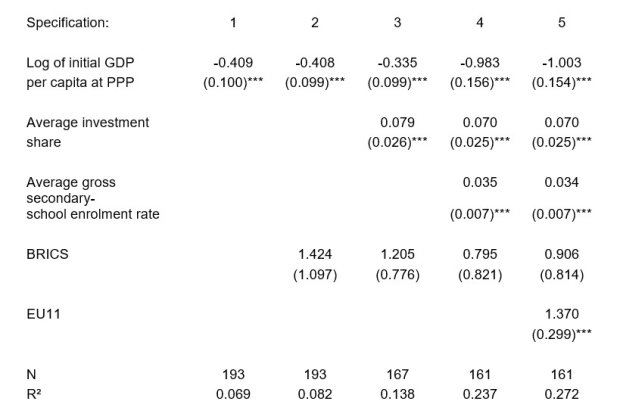

Table 1 - Cross-country regression results explaining average real GDP per capita growth, in %, 2006-2022

In this analysis, we aim to determine whether membership of the BRICS group has had any measurable economic impact, while controlling for standard growth determinants. Data were sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for all countries of the world. The dependent variable is the average real growth in GDP per capita over the period 2006-2022. Among the explanatory variables, we include the natural logarithm of GDP per capita at Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in 2006, as well as the average of the Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) investment share in GDP and the gross secondary-school enrolment rate over the entire period 2006-2022. Our main variable of interest is a dummy variable for BRICS membership, set to one for the five BRICS countries and zero otherwise.

Specifications 1–4 in Table 1 introduce the explanatory variables in a stepwise manner. The estimated coefficients for initial GDP per capita, the investment share and secondary-school enrolment exhibit the expected signs and are statistically significant at the 1% level. During the period under review, a general trend of convergence is evident, with richer economies tending to experience lower per capita growth rates. However, the rate of convergence is minimal: a 10% lower initial GDP correlates with only a 0.1% increase in annual growth rate. As anticipated, countries with higher levels of investment in physical and human capital show stronger per capita growth rates. However, in all the specifications the coefficient for the BRICS dummy variable is statistically indistinguishable from zero, indicating that BRICS membership, thus far, has yielded no additional economic benefits for its members, when controlling for standard growth factors. This outcome holds even when testing only the original four BRIC members.

Around the time BRICS was formed, 11 Central, East and Southeast European economies joined the European Union. Thus, in specification 5, we add a dummy variable for these new EU member states, alongside the other explanatory variables. This allows us to test an alternative path of economic and political integration – one that includes access to a large market, substantial transfers and the adoption of institutions promoting the rule of law. Unlike the BRICS dummy, the EU11 dummy coefficient is positive and statistically highly significant. On average, countries that joined the EU in the 2000s experienced annual real growth of GDP per capita that was 1.4 percentage points higher than the rest of the world, all else being equal. This is a substantial effect, comparable to the impact of a 20 percentage point increase in the investment share on the growth of GDP per capita.

In conclusion, BRICS membership has yet to show measurable economic benefits for Brazil, Russia, India, China or South Africa – unlike recent EU enlargement rounds, which have significantly boosted growth. So far, BRICS remains primarily a political project, largely composed of authoritarian states, led by China, that are seeking to counterbalance US influence and circumvent sanctions. The group also reflects the lack of integration of major emerging economies into post-Second World War institutions, such as the IMF or the World Bank, despite their growing economic strength in recent decades. The first expanded BRICS summit in Kazan, hosted by Russian President Vladimir Putin, was a major PR success; but it evokes comparisons with the ‘Potemkin villages’ that Field Marshal Grigory Potemkin famously rigged up to impress Empress Catherine II during her 1787 visit to Crimea, which Russia had annexed four years earlier.