Growth strengthens and inflation returns, but political risk warning lights are flashing red

31 January 2017

2017 could be a defining year for the European project, and the implications for Central, East and Southeast Europe may be significant. 10 key themes in 2017, by Richard Grieveson.

Our economic forecasts are under review ahead of our Spring Forecast, but slightly higher growth and a return of inflation look likely for the region this year.

1. Global uncertainty is one the rise.

The election of Donald Trump as the next US President has created major global uncertainty. For CESEE, the risks are numerous. The region includes a number of small, open economies which could be badly affected by any major changes to global trading arrangements (as has been hinted at by Mr Trump), or by a general downturn in global economic activity as a result.

2. EU unity will face further major headwinds in 2017.

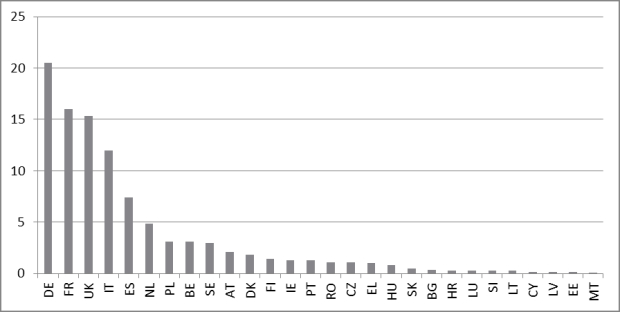

This rise in broader uncertainty comes on top of many existing challenges within the EU. Brexit negotiations could provide a strong motivation for cohesion among the other 27 EU members in the short term. However, unity over Brexit is unlikely to mask for long the clear divisions that exist in a number of areas. Infringements of EU law in some parts of CESEE, (lack of) sharing of refugees, splits over the bloc's relationship with Russia, and cleaning up the banking sector will all test the limits of the EU’s cohesion in 2017.

Much of this is political noise, and is unlikely to represent existential threats to the EU. However, two issues are much more serious. First, tensions over fiscal arrangements in the EU are becoming more obvious. Talks will begin in 2017 on the budget for the next financing period for the period after 2020. Many wealthier states are opposed to the greater EU control over national tax revenues proposed by the recent Monti report. Corruption issues around EU funds in some CESEE states have further angered net contributors in Western Europe. In the context of Brexit, with the third largest net contributor to the EU budget on its way out of the bloc, and therefore less money to go around, this will become an ever more pressing issue.

Second, control of the EU’s external borders and the durability of Schengen will remain a big problem. Schengen has been effectively suspended across some borders since 2015-16. The 2015 refugee and migrant crisis has left a difficult legacy. Without a feeling among citizens that the passport-free zone’s external borders are more concretely under control, the continued existence of Schengen could be threatened.

In both cases, the implications for CESEE are potentially very negative. A reduction in EU fund inflows would hit growth over a multi-year time horizon. Meanwhile, further disruption to Schengen could significantly hamper trade flows, particularly affecting the more open economies in CESEE.

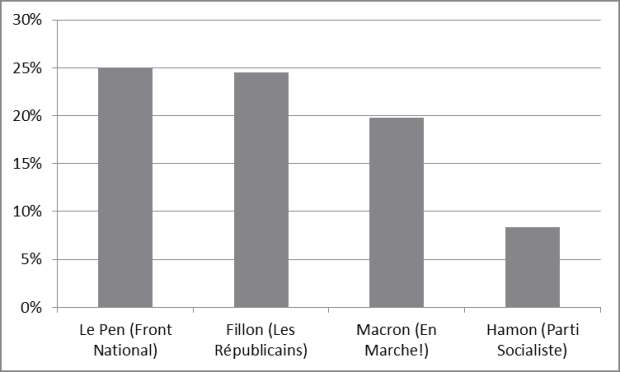

3. Elections in Western Europe are a risk, but this has been overstated.

This rise in uncertainty is exacerbated by a crowded election schedule in Europe, including potentially pivotal votes in Germany, France, and the Netherlands. In all three countries, populist parties are on the rise. Although some countries in Europe (such as Poland and Hungary) already have governments that can be described as “right-populist”, so far there are none in Western Europe. The governments in Hungary and Poland have pursued policies that are negative for the long-term health of their economy. However, their commitment to the EU (at least as a source of funds) remains clear. This is not the case for right-populists in Western Europe, which means the implications of such a government taking power in the EU’s “older” member states are potentially much more serious.

If right-populist parties make it into government in the Netherlands, Germany or France, they could have an important impact on policy that would have negative implications for CESEE countries. Negotiations over the EU budget, restoring Schengen back to full working order, potential discussions over child benefit payments to children in other member states from their parents, and various other issues, would become much more difficult to negotiate.

However, the chances of another populist party leading a government in the EU after elections in 2017 are probably overstated. A government led by the far-right in the Netherlands or France still looks unlikely, and Angela Merkel should remain as chancellor in Germany. Witnessing the harsh reality of the UK actually leaving the EU may even reduce the appeal of anti-EU sentiment in other member states (as may have been the case in the recent Austrian presidential election).

In the Brexit negotiations, the UK will prioritise controlling immigration, which will have important implications for CESEE countries. Fewer workers will be able to go to the UK to learn new skills and send home remittances, while funds for the EU budget (of which CESEE is the major beneficiary) will likely be reduced.

A more general problem for policymaking in Europe is that the old left-right division of European politics has started to break down. A new division, which can be roughly simplified as those against globalisation on one side and those in favour on the other, has appeared. This is impossible to map onto existing party groupings, which has resulted in a general fragmentation of party politics. The result is that forming cohesive coalitions capable of enacting reforms is much more difficult.

4. Political risks will remain high in a number of countries in CESEE.

Country specific political risks will remain high in CESEE this year, and in many cases this will have negative economic implications. In Turkey, the central bank may be limited in its ability to tighten monetary policy to support the lira by political considerations. Political volatility could damage investor sentiment. Political risk also remains high in Hungary and Poland, which may dent confidence among both foreign and domestic investors.

Ukraine remains unstable, and the election of Donald Trump as US president introduces an unpredictable new variable. There is uncertainty about Mr Trump’s commitment to NATO, which has caused a lot of unease in Europe. Mr Trump also appears keen to improve relations with Russia, and may be more sympathetic to its interests in eastern Ukraine. The conflict there will continue to hold back the Ukrainian economy. Meanwhile, Mr Trump’s apparently more pro-Russian stance will unsettle those countries in CESEE which fear their larger eastern neighbour (notably the Baltics and Poland).

The risks of instability in the Balkans are higher than they have been for some time. Stability in the region has been underpinned by a US “stick” and an EU “carrot” in the past 20 years. The US has ensured regional security, while the EU has held out the prospect of membership in return for good behaviour. There are reasons to think that both roles will be reduced in 2017. The new US president, Donald Trump, is unlikely to take much of an interest in the region. Meanwhile, enlargement fatigue, and a focus on sorting out internal problems, leaves the EU with a diminished role in the Balkans.

The fallout could be highly destabilising. The Balkan region includes a number of essentially frozen conflicts, which could heat up if external actors supporting stability withdraw. The most obvious potential trigger point is the wish by Milorad Dodik, the president of the Republika Srpska, to hold a referendum on the independence of the entity from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Should this take place, it could set off a domino effect of competing territorial demands in the region.

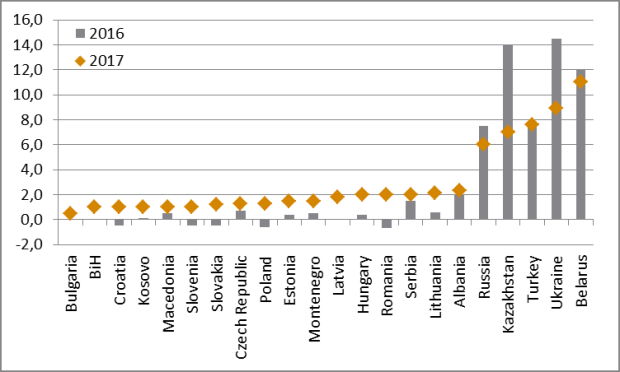

5. All CESEE countries covered by wiiw are likely to post positive consumer price inflation growth in 2017, for the first time since 2012.

This is largely because of the rise in global oil prices. Beyond energy, however, upward pressure on prices remains limited. Inflation will moderate from high levels in the CIS as currencies strengthen.

6. Nominal sovereign debt yields will start to rise in CESEE.

The European Central Bank (ECB) will continue with its quantitative easing (QE) programme. This will help to maintain stability in CESEE debt markets. However, US monetary tightening will continue, and may even accelerate, which will put upward pressure on CESEE nominal sovereign debt yields, particularly in those countries with weaker fiscal fundamentals and/or higher political risk.

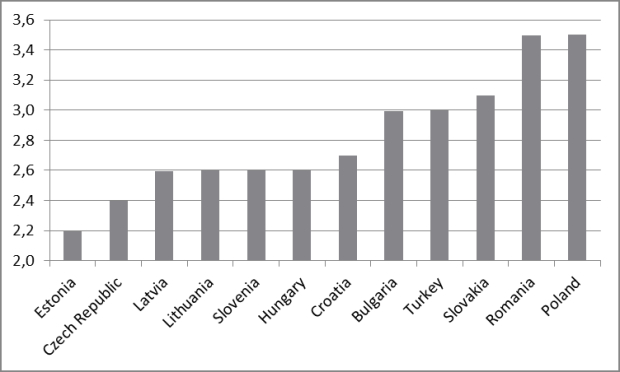

7. Overall, EU-CEE economic growth will strengthen this year.

Growth will be well above the level of Western Europe, indicating continued convergence in income levels. Economic momentum in the Visegrad states will mostly pick up, after flagging in 2016 as investment spending slowed. Despite political challenges, Poland and Hungary will both grow quite strongly. Meanwhile Romania will again be a stand-out performer in South East Europe, although growth will slow from the level of 2016.

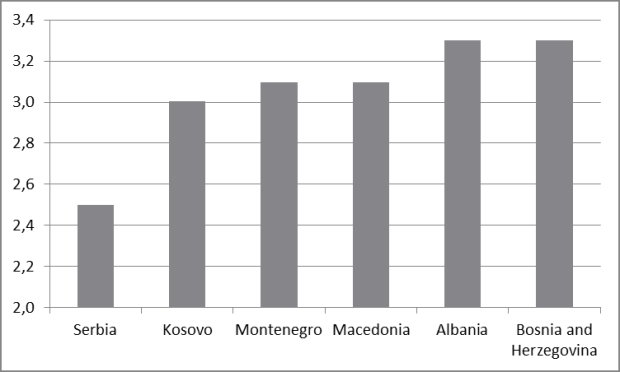

8. Economic growth in the Western Balkans will continue to strengthen.

The rebound in Serbia—which had lagged the regional recovery somewhat—will remain on track, and may well strengthen. Nevertheless, regional growth will remain low by historical (pre-crisis) standards and not at a high enough level to achieve substantial progress on convergence with Western European income levels.

Three factors will continue to prevent a higher growth rate in the region. First, post-crisis macroeconomic restructuring—and in particular the unwinding of large current account deficits—is not yet complete. Fiscal policy remains broadly restrictive, and domestic demand is still constrained. Second, the region faces greater structural impediments to growth than most of EU-CEE. These include infrastructure bottlenecks, banking sectors burdened by bad loans, and slow progress on some reforms, notably of the judiciary. Third, political risk remains a problem (see above).

9. The meagre recovery in the CIS will continue.

Russia will return to growth and momentum in the Kazakh economy will strengthen, underpinned by higher oil prices. However, the region will remain by far the weakest performer in CESEE. Belarus may manage to eke out positive growth for the first time since 2014.

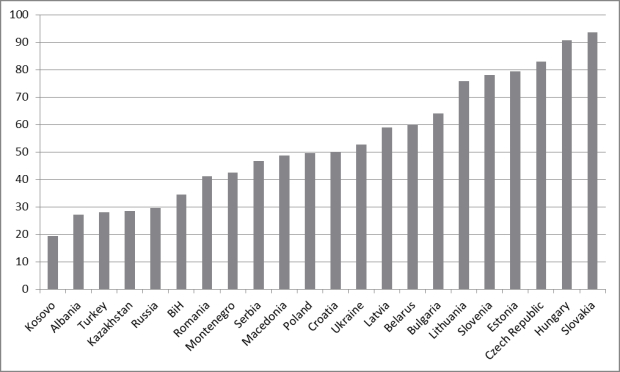

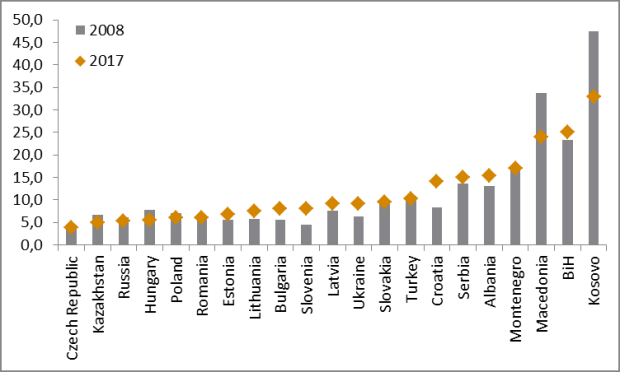

10. The unemployment rate in EU-CEE will fall further.

The rate of joblessness will be particularly low in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania. Within EU-CEE, only in Croatia will the unemployment rate remain in double figures. Outward migration and stronger economic growth have resulted in a tightening of most labour markets in EU-CEE. By contrast, the rate of joblessness will be almost 20% in the Western Balkans, where structural deficiencies remain, and the safety valve of outward migration to Western Europe exists to a much lesser extent.

In many countries, the unemployment rate in 2017 will still be higher than it was in 2008. If anything, this measurement probably overstates any decline in unemployment, with labour markets in many states having shrunk since 2008, and large numbers of workers having emigrated to Western Europe.