Honouring promises

17 June 2019

If the EU delays the opening of accession negotiations for Albania and North Macedonia, it will send a terrible signal to the Western Balkans.

By Richard Grieveson

Photo: 'Eu flag inside a spiral', European Parliament/Pietro Naj-Oleari, CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

At the EU’s General Affairs Council to be held on June 18th in Luxembourg, EU leaders are set to decide whether or not to open accession talks with North Macedonia and Albania. The European Commission has already stated its support. However, it appears likely that the Council will not allow talks to start.

Several member states, notably France and the Netherlands, appear particularly keen to delay accession. French President Emmanuel Macron would prefer to focus on reform of the EU as it is before accepting new members. France recently published a Western Balkans strategy that did not even mention enlargement. Meanwhile, the Netherlands has a particular issue with Albania (the Dutch government asked the European Commission to suspend visa-free travel for Albanians at the start of June, owing to concerns about organised crime).

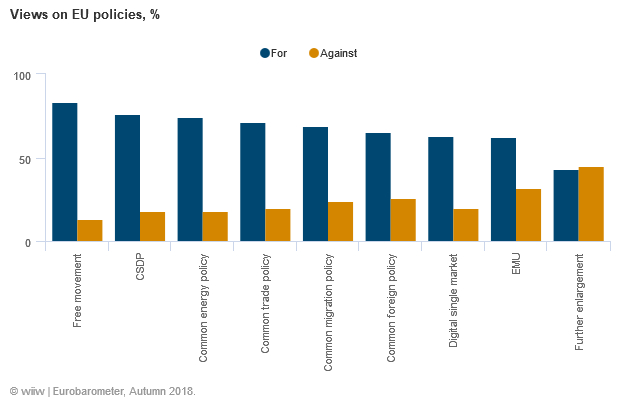

Germany and others are also understood to be quite lukewarm. The experience of Bulgarian accession in 2007, in particular, left many in Western Europe feeling that more could have been done pre-accession to strengthen the rule of law. 12 years on, Bulgaria and Romania are still under special monitoring of corruption, judicial reform and organised crime. These deliberations among politicians, moreover, take place against the backdrop of more general hostility to enlargement among EU citizens. Of the questions about general EU policies asked by Eurobarometer in its latest survey, enlargement was the only one that did not have majority support (see chart below).

A mistake

If the Council does not give the go-ahead for the start of accession talks, as expected, it will send a terrible signal to the region, and especially to North Macedonia and Albania. Zoran Zaev, the Prime Minister of North Macedonia, will have particular reason to feel aggrieved. He has invested a huge amount of political capital in resolving the name dispute with Greece, in order to theoretically pave the way for NATO and EU accession. The former looks quite likely, but the latter is the real prize.

More broadly, though, a delay to accession negotiations would go against the EU’s own promises, and an agreed process and set of benchmarks. The European Commission has made its position clear: both countries are ready to start accession talks. According to the Commission assessments of May 2019, North Macedonia is doing as well as Serbia and Montenegro, two countries that have already started negotiations with the EU for accession. To reject North Macedonia in this context would be particularly bad.

Political constraints

It is easy, of course, for people who do not have to answer to voters—the European Commission for example, or a think tank in Vienna—to tell politicians what they should do. We are not up for election. However, four things seem clear to us when thinking about the domestic political context in Western Europe.

First, concerns about organised crime and the mafia are understandable. However, such organisations do not need EU membership, or even visa free travel, to operate across the EU. The mafia will find a way whatever the context: the people who lose from a delay to EU accession (and, possibly, a removal of visa-free travel) are ordinary citizens. Moreover, the strengthening of the capacity of the state that the EU accession process involves is actually what countries like Albania need to be able to tackle organised crime domestically.

Second, the Western Balkans is clearly part of “core” Europe (whatever that may mean). If may be harder to sell EU accession of, say, Georgia or Ukraine to Western Europeans, but the Western Balkans is already surrounded by the EU.

Third, the region is important from a security perspective for Western Europe. This was reinforced quite clearly by the 2015-16 migration crisis. Surely, Western European politicians can make the case that a more developed Western Balkans, with better functioning institutions and more resources at the disposal of the state, is of clear benefit to Western Europe from a security perspective. And, moreover, that EU accession is the best way to guarantee this.

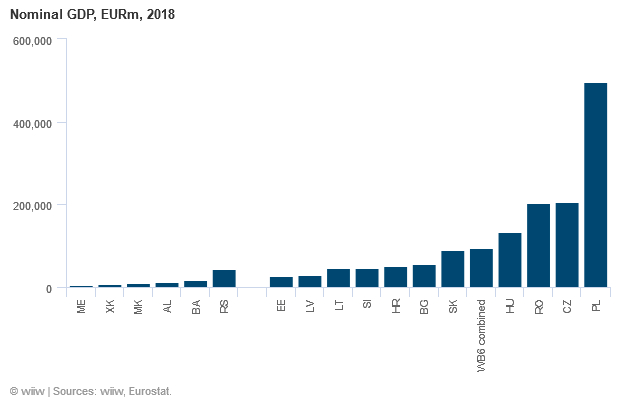

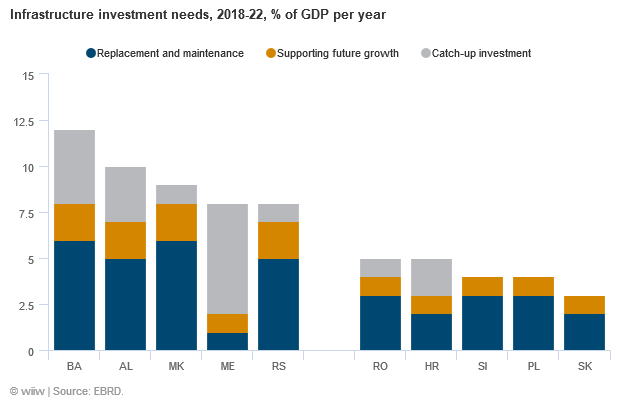

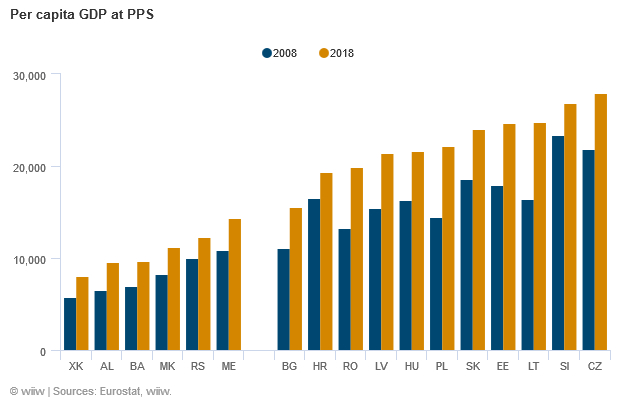

Finally, the idea that the Western Balkans will become a fiscal drain on EU resources does not stand up to much scrutiny. Even Serbia, the region’s biggest country, has an economy smaller than that of Lithuania. Combined, the six Western Balkan countries have an economy a bit bigger than Slovakia (see first chart below). If all six Western Balkan countries joined the EU tomorrow, and immediately reached an absorption capacity of EU funds level with the current top performer Hungary (a bit over 4% of gross national income net over the last five years), this would necessitate a barely noticeable increase in the size of net contributions from the likes of Germany and France. Meanwhile the impact of full access to the EU budget on the region’s development, and especially of much-needed public infrastructure investment, could be game-changing (see second chart below).

A better way

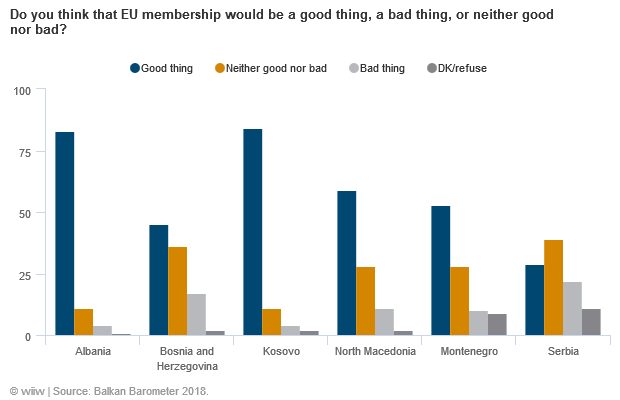

It would be naïve to expect EU accession for the Western Balkans anytime soon. We have already expressed our scepticism that 2025 is realistic as a target date, even for Serbia and Montenegro. However, the starting of accession negotiations for Albania and North Macedonia should proceed without delay. Moreover, the EU must remain committed in its engagement with the reform process in the Western Balkans. Only with serious EU efforts, and the (still very strong) carrot of eventual membership, can the region forge a stronger development path and start to catch up with CESEE peers (see chart below). This includes taking a more hands-on approach to solving political conflicts in the region, improving governance standards, upgrading connectivity and infrastructure, deepening local capital markets, and helping the transition to digitalisation (for more details on these areas see our report on accession prospects from last year).

If the EU does not do this, the role of other powers in the region will grow. This is unlikely to be positive, for the EU nor the Western Balkans. Russia’s influence can be overplayed, not least because it does not commit significant resources, but it has the potential to play a destabilising role in some countries. Meanwhile the arrival of China in the Western Balkans poses a more serious threat to the EU, owing to its potentially significant infrastructure investments. This also brings risks of higher corruption, a lack of spill-overs to the domestic economy, increased debt burdens, and unwelcome (from an EU perspective) political influence.

Conclusion: get serious

Even Ukraine with its Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) is in some ways now more integrated with the EU than the Western Balkans is. Although Ukraine does not have the so-called “accession perspective” of the Western Balkans, the current stance from some EU capitals suggests that this in the end may have little meaning. Yet the Western Balkans belongs in the EU, and there is no way to get away from that, even if some would like to.