Iran: Economic troubles create political risks

04 September 2018

As in the past, US sanctions risk producing a more hard-line government, but the Iranian administration should pursue a more moderate course.

by Mahdi Ghodsi

photo: Iran Grunge Flag, Nicolas Raymond, CC-BY-2.0

- As we argued in a recent report, new US sanctions on Iran will create big problems for the economy.

- For the Iranian authorities, there are two possible paths from here: a moderate or a more hard-line stance.

- A hard-line government is possible, and some reformist ministers have already been sacked.

- However, the authorities have seen in the past how damaging this can be and as a result should opt this time for a more moderate course.

- The EU wants to stay engaged and do what it can to maintain ties. This has had a positive signalling effect, but will not do much to limit the negative economic fallout.

As we argued in a major recent study, the fallout from the US decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, the so-called “Iran deal”) and impose new sanctions on Iran will be significantly negative for the country’s economy. Ever since US President Donald Trump made his intentions to scrap the deal clear in 2017, the economy started to feel the pain. The economic and social fallout has already been significant. Iran’s currency, the rial, has collapsed, and inflation has skyrocketed.

Social protests have been seen on various occasions across the country this year, partly driven by perceptions that the government has bungled its response. In response to market panic, the government hastily attempted to unify the country’s dual exchange rates to a rate close to the market rate (which had been recommended by many economists including the IMF). However, the government’s implementation of this policy was sub-optimal. In the implementation process the government prohibited any transactions of currency in exchange bureaus while tightening the supply of the hard currency to the market through the banking system, because they feared losing currency reserves under the pressure of incoming US sanctions. Imports of hundreds of products were prohibited and only primary commodities were permitted to be imported with the official rate. This gave impetus for further deprecation of the exchange rate in the black market and hoarding of imported products put pressure on the price of products. This was perceived as systematic corruption by the public, and led to further protests in many cities.

Two possible paths for Iran from here

Iran is currently suffering from long-standing structural weaknesses in its economy, and needs major reform. Combined with new US sanctions, this puts Iran is in a very difficult position, and there are no easy choices for the administration. However, it is clear that there are two paths that Iran could go down, and which one the state decides to take will have a big bearing on how the economy does.

One path is to seek to manage the fallout from new US sanctions in a sensible way and seek to minimise the damage to the economy. The Iranian government has recently been seeking advice from prominent economic professors across Iran to find a solution to the most pressing issue, the falling currency, and found a short-term solution by removing many of the restrictions in the currency market and reversing the previous moves. Although it is not a concrete, appropriate plan for the long-run to have two distinct exchange rates (official and market), it shows a good signal that the Iranian economic policymaking is converging towards international best practice, and being informed by economic expertise.

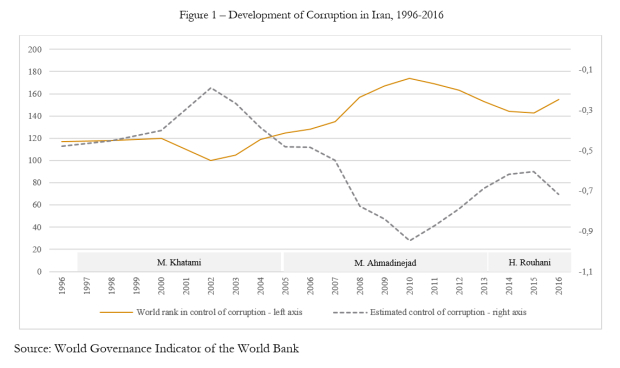

In contrast, the second path would be to recruit hardliners to the cabinet who have better connections with security forces and intelligence services and could possibly find ways to bypass US sanctions. This would be effectively a repeat of the damaging policy pursued during the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (see for example section 2.4 of our recent Iran Report). Then, as now, Iranian hardliners were helped by US hostility (including Iran as part of ‘axis of evil’ in 2002 by President George W. Bush). The period of hardliners gaining power on the back of US hostility in the 2000s coincided with increased corruption in Iran then (see Figure 1). Rent-seeking bargained for higher gains, while the economy was exposed to large international risks as the administration sought to evade US sanctions. A move in this direction would lead to more corruption and embezzlement in Iran, and could prompt large-scale social unrest. Meanwhile, removing technocrats with economic competence from the cabinet (who had had some success, including boosting the economy by increasing oil revenues, new jobs, and better regulations of investment and the banking system) would not be a very good strategy.

Heading towards a hard-line government?

Unfortunately, the second route is a possibility at this stage. Iran may end up with a more hard-line government. On August 13th, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, acknowledged the impact of sanctions and the government’s mismanagement of the economy. This critique of the government came along with the removal of some reformist members of the government. The parliament impeached and sacked Ali Rabiei on August 8th, a reformist who had served as the Minister of Labour since August 2013 (the first and second Cabinet of Mr Rouhani) and Masoud Karbasian on August 26th, another reformist who had served as Finance Minister since August 2017. These impeachments appear to be a political move to prepare the cabinet for economic war with the US. No replacements have so far been announced.

Even Iranian President Hassan Rouhani (a relative moderate) is coming under pressure. On August 28th Mr Rouhani attended a session in the Parliament to answer questions on five problematic economic issues:

- Smuggling of products and currency

- Disconnection from the international banking system (continuation of sanctions)

- High unemployment rate

- Economic recession

- Large depreciation of the rial

These issues are not new for Iran and existed long before the presidency of Mr Rouhani. However, after the US withdrawal from the JCPOA, lawmakers took the opportunity to deflect the blame onto Mr Rouhani, despite him having been in office for only around one year. Mr Rouhani has made visible improvements to the way the economy is run his first term in office using some evidence-based policy, and has asked for moderation and solidarity in these difficult times. However, members of parliament (which has a majority of moderates and reformists) were not convinced enough, and wanted to refer his alleged mismanagement of the economy to the judiciary as a breach of law. Although referring the case to the judiciary is an extreme measure, parliament’s criticism of Mr Rouhani is not without foundation. Deep structural economic reform is needed to overcome Iran’s long-standing economic problems, and Mr Rouhani did not offer a framework for such a reform. Nevertheless, the head of the judiciary is directly elected by the Supreme Leader and a compromise with the judiciary is very likely.

A three-pronged response

Aside from ministerial changes, the authorities have been formulating a broad set of responses. During the past few months, the heads of three branches of the Republic, namely the judiciary, legislative, and executive government, have had several meetings to discuss how to deal with the new US sanctions. It could be the case that they have already reached a consensus to attempt to control the situation with a compromise, which might be:

- The government to reshape its cabinet and prepare itself for economic war.

- The parliament to legislate some pending regulations such as the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) to allow Iran to become fully connected to the international banking system.

- The judiciary decisively and quickly to conduct judicial process and punishment on recent disturbances in the market to safeguard any possibility of corruption during the time of sanctions.

Going in a hardline direction would be a mistake

The US decision to withdraw from the JPCOA and impose new sanctions on Iran is deeply regrettable, and has been criticised by many other international partners, including the EU. However, while clearly Iran will suffer, if the authorities choose to respond by taking a more hard-line approach, the situation for the economy and the population will become even worse. We see two reasons why the Iranian government should take a more moderate approach to US hostility than has been the case previously.

First is the experience of the past. As stated earlier, previous hard-line governments have been characterised by corruption and embezzlement, a deterioration in economic and social conditions, and neglecting economic expertise in formulating policy. The current path that the government has taken, in establishing a platform by which it seeks the advice of economists and other experts in the field, is a welcome indication of a wiser approach in governance.

Second, it would significantly decrease the chance of getting help from international partners. Iran has received a certain amount of sympathy from other countries as a result of the US actions, but if it takes a hard-line turn, these partners may be less willing to help. Iran should work on continuing to improve diplomatic relations with friendly countries, in order to be better able to withstand the impact of new US sanctions. It is worth mentioning here that some international partners are seeking exemptions from US sanctions in order to maintain economic ties with Iran. These improved ties could easily be undone if Iran becomes hard-line (the recent threat to block the Strait of Hormuz being a worrying shift in this direction). As was seen during the presidency of Mr Ahmadinejad, extreme and unwise words could lead to a wider coalition of countries imposing crippling sanctions on Iran.

The way forward: constructive approach with EU help

Iran needs to learn from the past mistakes and avoid conflict with both the East and the West (reversing a slogan from the time of the Islamic Revolution, which called for “No East, No West, Only Islamic Republic”), and instead continue to improve relations with international partners. One and a half decades of dialogue with the EU has brought some positive results, and brought Iran closer to the US’ European allies. Notably, the EU updated the Blocking Statute to be compatible with the new US sanctions, one day after US re-imposed them. This statute forbids European companies from abiding by the sanctions, and allows them to claim reimbursement of US penalties through courts in their local EU member states. Eventually, this will enable the EU to file a dispute settlement case in the WTO if European firms are prohibited from trading with the American market.

The practical outcome of this move may not be that significant. European multinational enterprises will now anyway leave Iran, as they want to maximise their profits with the least risk, and they prefer the access to the US market over Iran. However, this regulation has a positive signally effect towards Iran, and acknowledges that fact that the population voted for the moderate government of Mr Rouhani to strengthen this relationship. In addition, a first support package was adopted by the European Commission on August 23rd worth €18m. This covers environmental challenges, drug harm reduction, SMEs and trade in Iran, and will be implemented by the International Trade Centre in Geneva. Most importantly, on August 29th, the Supreme Leader of Iran advised the Cabinet to continue relations and negotiations with Europe. Therefore, by continuing moderate reforms in Iran and avoiding the hard-line path of the past, Iran can seek international support to help manage the negative consequences of US policy.