Iran: Rouhani visit to Austria comes at a difficult time

03 July 2018

Austria and the EU are keen to help, but a new wiiw study on Iran concludes that US sanctions will add to an already extensive list of economic challenges.

By Mahdi Ghodsi

- Iranian President Hassan Rouhani is this week visiting Europe, including Austria, at a crucial time for his country, with the US having pulled out of the nuclear deal, and set to impose new sanctions on Iran in August.

- Austria and the EU could have vital role to play in mitigating the negative fallout, although the room for manoeuvre without risking a significant rupture with Washington is limited.

- To coincide with the visit, wiiw has published a major new study on the challenges and opportunities in the Iranian economy, putting recent developments in the context of four decades of economic underperformance.

- We conclude that a new round of US sanctions will exacerbate an already difficult situation, and have a big negative impact on economic growth. This risks undoing much of the good work of recent years.

- Fundamentally, the Iranian economy has some big strengths, including access to natural resources and a decent level of human capital. What it needs most is technology transfer from the West, something that look highly challenging in the current environment. As long as Iran remains in conflict with the US, it will be difficult to significantly lift the level of economic development.

Mr Rouhani is this week vising Switzerland and Austria, his first foreign visit since the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, more commonly referred to as the “Iran nuclear deal”). Switzerland and Austria are the two neutral countries that hosted atomic negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 (the permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany).

Both Switzerland and Austria are important partners from the Iranian perspective. Since formal diplomatic ties between Iran and the US were broken in 1979, Washington and Tehran have used the embassies of Switzerland in other’s capital city to conduct any necessary diplomatic business. Meanwhile, Mr Rouhani’s visit to Vienna will, among other things, mark 160 years of diplomatic relations between Austria and Iran.

A big moment for Austria and the EU

On July 1st, Austria took over the presidency of the Council of the EU. Mr Rouhani will visit both the Austrian Prime Minister, Sebastian Kurz, and the Austrian President, Alexander Van der Bellen during his visit to Vienna. The US withdrawal from the JCPOA, and what comes next, are likely to be high on the agenda. Prior to the US withdrawal from the deal, EU leaders reiterated their interest in preserving the agreement, which has been achieved after one and a half decades of EU-Iran dialogue. This visit, therefore, could have an important role in finding a solution to counter, or at least soften the blow from, US secondary sanctions against Iran, which will come into effect in August. Prior to this visit, Iran gave a deadline to the European Union to submit the EU proposals to preserve the deal.

Mounting challenges for the Iranian economy

Whatever the EU side able to do, it is likely that the Iranian economy will take a big hit from the upcoming US sanctions. Indeed, the impact of the US withdrawal, and concerns about the new round of sanctions, have already had a significant impact on the Iranian economy. This has included a substantial devaluation of the Iranian rial, panic in the domestic market, and capital outflows since January 2018. Despite very high real GDP growth of 12.5% in 2016/2017, the sanctions relief which had been brought about by the JCPOA has not yet been fully felt by the Iranian population.

New wiiw study highlights deeper problems in the Iranian economy

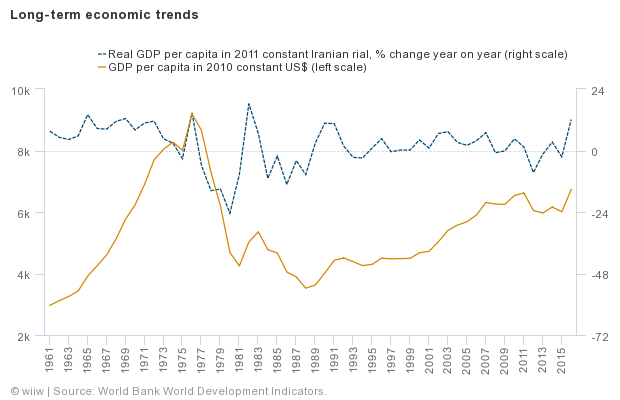

Any further negative fallout will only add to an already difficult set of longer-term structural barriers to development, according to a major new wiiw study on the Iranian economy. Iran’s economy is yet to return to its 1976 peak in real per capita GDP terms (see chart below), reflecting the numerous challenges it has faced in recent decades. US-Iranian animosity has been one of these, and has certainly damaged Iran’s business environment.

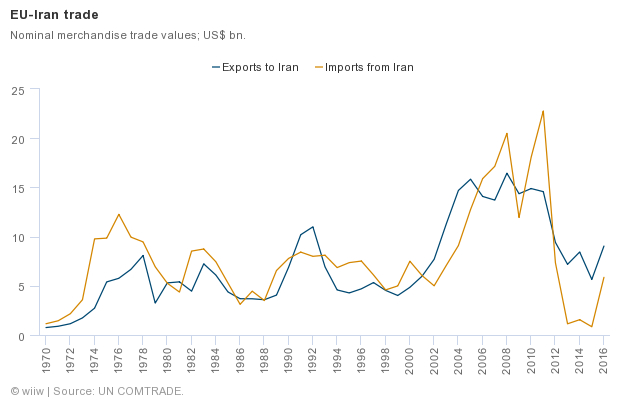

Moreover, as demonstrated in our new study, despite positive trends in some areas, Iran has clear shortcomings in terms of its global competitiveness. The imprudent policies of Iran at the time of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) had significant and negative implications for the economy. This led to, among other things, an intensification of international sanctions in 2012, which caused EU-Iran trade to plummet (see chart below).

Progress under Rouhani has been impressive…

In contrast, the more moderate President Rouhani and his technocratic government have managed to stabilise the economy, with a better diplomatic and foreign policy leading to sanctions being removed, and with a prudent economic reform agenda covering the following issues:

- First, the Rouhani government managed to reduce inflation to less than 10%. If sustained further, this could strengthen the monetary framework and would be a major achievement in the context of the past four decades, although the steep currency depreciation over the past few months, and the imposition of drastic currency controls in response (and the emergence of a ‘black market’ for foreign exchange), suggest that these achievements are unlikely to be sustained.

- Second, the government recapitalized and restructured banks to further safeguard financial stability.

-

Third, the administration attempted to connect Iran to international financial and currency markets. While sanctions are the major impediments to this, reforms in the banking system were also required, including by addressing Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) frameworks, which are parts of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). While the government asked legislators to adopt the respective law, a lack of political will still hinder the process.

- Fourth, around 500,000 new jobs have been created each year since 2013, which is almost seven times the annual job creation during the period 2005-2013 according to Iranian Statistics Centre.

- Fifth, by increasing transparency of domestic policies, Mr Rouhani has been trying to decrease the role of state-owned enterprises as well as that of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in the economy, which still seems to be one of the big impediments of the whole reform process.

…but this could now be undone

Following the implementation of the JCPOA, economic growth rose. However, this was mostly due to higher production and exports of oil, a capital-intensive sector, and has therefore not translated into equivalent employment gains. In 2016/2017, as oil production reached its capacity, growth slowed down. Meanwhile other (non-oil) sectors have not yet received enough investment to boost the economy further. This is generally evident in the construction sector, which has historically been a good bellwether of the wider performance of the Iranian economy.

Investment has also struggled because Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) and many Western firms feared uncertainties regarding the future relationship between the US and Iran. Although these firms initially showed their interest by rushing in after the JCPOA to sign memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with Iranian delegates and companies, they now fear penalties and punishments from secondary sanctions by the US government. It will be also difficult for other signatories of the JCPOA (e.g. the EU) to incentivise companies to stay in Iran. For example, it would be costly for other governments to compensate companies for the penalties enforced by the US government.

After the US withdrawal from the JCPOA, the Iranian authorities urged European countries to find strategies to counteract American secondary sanctions. The Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khameni, asked that major European countries give guarantees so that Iran stays in the atomic deal. According to statements by other Iranian officials, it seems that the government is mostly focused on guarantees to allow it to maintain sales of oil, and less on ensuring further foreign direct investment (FDI) from European MNEs.

This, in our view, is a mistake. With its relatively high level of human capital, know-how, and access to natural resources, what the Iran economy needs most is the technology to boost its industrial capacities. This could be better achieved via FDI of MNEs from advanced economies, which have advantages in high-technology sectors such as chemicals, optics, IT, automobiles, and other manufacturing machineries. However, at present the data show that Iran has stronger trade and FDI links with China and Russia, both of which also lag behind the West in technological advancements.

What could be done?

The best strategy to address these issues, which has been also recently recommended by some Iranian political activists, would be to conduct further negotiations and find a rapprochement with the US. This would also improve expectations with regard to Iran’s near-term economic prospects, and help to stabilise the exchange rate, thereby setting up pre-requisites for a gradual easing of currency controls in the medium term.

However, there are serious obstacles to a possible new deal between Iran and the US. First, the abrupt change in US policy after President Trump took office calls into question the credibility of a possible future deal with the US from the Iranian perspective (Mr Trump’s decision makes it easy for hardliners in Iran, always distrustful of the US, to say “we told you so”). Second, finding a better deal with the US that can fully satisfy the demands of the US government – recently announced by the US secretary of State Mike Pompeo – would require a lot of concessions on the Iranian side, many of which may be unpalatable (especially in the current economic context).