Labour’s falling share of national income – and what to do about it

21 March 2018

Centralised wage bargaining or a larger role for the state have limited the fall in the wage share since 1960.

- In countries where the role of the state has been reduced, the existence of a more centralised wage bargaining system has limited the extent of the fall in the share of labour in national income. In countries with less prevalent collective bargaining systems, a similar effect can be achieved by higher government spending.

- These are the central findings of a new wiiw study which analyses the impact of ‘corporatism’ – cooperation between business, labour and state interest groups – on the long-run development of the wage share in 42 industrialised economies for the period 1960 to 2010.

- The study concludes by arguing for a stronger role for centralised wage bargaining in economic policy-making, especially in countries where the share of government spending in GDP is low.

Central banks and international economic institutions have argued for decades in favour of slashing the bargaining power of trade unions and the capacity of governments. Now, however, they are starting to change their stance.

The paradigm shift comes with the observation that in much of the developed world, less cooperation between workers and employers in setting wages, and a reduction in the size of the government sector, have evolved together with higher inequality and a decline in the wage share.

In addition, the political repercussions of these developments – notably greater success for populist parties and rising authoritarian tendencies in some countries – have prompted serious reflection in economic thinking.

To fight low wage growth, central bankers and international economic institutions are increasingly calling for more centralised wage bargaining, and rediscovering the benefits of cooperation between business, labour and state interest groups – ‘economic corporatism’.

Attempts to explain the falling labour income share have focused on the dynamics in technological change and globalisation. By contrast, the impact of corporatist arrangements on the wage share has not been analysed extensively.

Corporatism associated with higher wage share

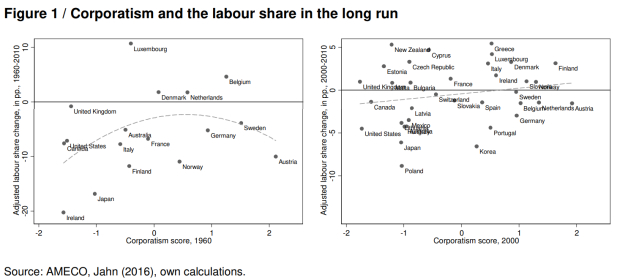

To address this deficiency, the new study analyses the impact of a new corporatism indicator on the long-run development of the wage share for 42 industrialised economies for the period 1960 to 2010. In addition, it looks at interactions with other institutional settings.

For most industrialised economies with lower and intermediate government outlay shares in GDP – in the range of 20-40% – as well as higher or average levels of corporatism, there are higher levels of the wage share of around 60-65%. These shares typically stagnated or only fell slightly (by around half a percentage point of GDP per year) over the period observed.

By contrast, countries with low levels of corporatism, as well as lower or average government expenditure shares in GDP, had much lower wage shares. Moreover, these shares declined much more strongly over the period (by up to two percentage points of GDP per year). In addition, in countries where wage bargaining is less prevalent, higher government spending acts as a substitute for corporatism.

Policy implications

The results are clear: in countries where the role of the state has been reduced, the existence of a more centralised wage bargaining system has limited the extent of the fall in the share of labour in national income. Meanwhile, in countries with less prevalent collective bargaining systems, a similar effect can be achieved by higher government spending. Governments should therefore allow for a stronger role for centralised wage bargaining in economic policy-making, especially in countries where the share of government spending in GDP is low.

Photo credits: Advantage Austria.