Measuring globalisation: A new database on economic openness

06 October 2020

To facilitate research on globalisation and related issues, this article introduces a new data set with different trade, financial and overall openness indicators for 216 countries over 1960-2019.

By Philipp Heimberger

photo: iStock.com/Studio_Serge_Aubert

The growing market integration of international trade and finance has been a central feature of the globalisation process over the past decades, affecting the lives of millions of people around the globe. The socio-economic effects of economic globalisation have been subject to heated academic and political debates. Social scientists have studied a broad array of questions, such as: How does the reduction in transaction costs of moving capital and jobs across borders affect taxation and spending choices of national governments? Does trade openness affect developing countries differently than advanced countries? What are the domestic political effects of growing market integration?

Finding robust answers to such important questions is not straightforward at all, and reported research results have often differed substantially. The relevant debates use a great diversity of concepts to describe the extent of international economic integration: terms like ‘trade openness’, ‘economic integration’, ‘trade liberalisation’ and ‘globalisation’ are widely used. The same observation holds true for the financial dimension, where terms like ‘financial openness’, ‘financial integration’ and ‘financial globalisation’ are used regularly and often interchangeably. In analogy to this variety of terms and concepts, a large variety of measures of economic openness have been developed. These measures typically emphasise different aspects of economic integration. As a consequence, not only the definition, but also the measurement of openness has varied considerably; and researchers have widely acknowledged a corresponding lack of consensus on how to best measure economic openness.

To bring light into the jungle of measuring openness, I have teamed up with Claudius Gräbner, Jakob Kapeller and Florian Springholz. In a paper recently published in the Review of World Economics, we provide a comprehensive survey on existing measures of openness. We compile a new data set of different trade, financial and overall openness indicators, which consists of 216 countries over the time period 1960-2019. We have set up a website, which can be used by interested researchers to access the data. Via this website, we will also provide regular data updates.

In the paper, we introduce a typology of openness indicators. We also explain some of the pros and cons of using different measures in applied research. We then discuss trends in how economic openness has varied across time and space when looking at different data dimensions. Finally, we illustrate that the consequences of choosing among these indicators can have a stark impact on the results obtained from regression analysis.

A typology of economic openness

Existing measures of economic openness can generally be understood as the degree to which non-domestic actors can or do participate in a domestic economy. We group them in two major ways: The first grouping refers to the type of openness – ‘trade’ or ‘financial’ – the indicator is trying to measure; and the second one relates to the sources utilised in composing the openness measure. These sources are either aggregate economic statistics (so-called de-facto measures) or assessments of the institutional foundations of economic openness, i.e. the legally established barriers to trade and financial transactions (de-jure measures). De-facto measures are outcome-oriented indicators, reflecting a country’s actual degree of integration into the world economy. In contrast, de-jure measures, are based on evaluating a country’s legal framework. Furthermore, ‘hybrid’ measures try to incorporate information on trade and financial aspects, while “combined” measures aim at integrating information on de-facto as well as de-jure aspects of economic openness.

De-facto and de-jure facets of openness need not be consistent for a given country. For instance, a country can have a defensive legal stance in terms of openness, but still play an important role in the world trading system – e.g. due to its special position as a trade hub (e.g. China) or as a financial hub (e.g. Malta). At the same time, a country may be open to trade in terms of institutions and policy, but nonetheless lag behind in terms of its relative integration in international trade due its geographic remoteness (e.g. Canada) or lack of technological development (e.g. Uganda).

Based on our typology, we compile more than thirty different openness indicators from the literature, and integrate them in one data set. By far the most prominent trade openness indicator is trade to GDP (measured as the sum of imports and exports as percentage of Gross Domestic Product). The predominance of the trade/GDP indicator masks the fact that alternative indicators of trade openness, such as de-jure measurements based on tariffs, do exist and may be more appropriate for some research questions than the more visible and common alternative.

We also point out some important reservations about the use of trade relative to GDP in empirical work: the Trade/GDP measure captures cyclical swings of economies (because of the normalization by GDP). The financial crisis in 2008/09 made several countries look ‘more open’ in terms of Trade/GDP, simply because of the disproportionate effect of the crisis on GDP. Furthermore, the use of GDP in the denominator corrects not only for the size of a country, but also for its level of economic development (holding everything else constant, the trade-to-GDP ratio decreases with higher GDP). As a result, it is much more difficult for larger and more dominant economies to achieve a high Trade/GDP ratio - countries typically regarded as "open", such as the USA or Japan, therefore appear only towards the bottom of the respective Trade/GDP rankings. Finally, the use of Trade/GDP also negates the dimension of financial globalisation. Here, researchers have adopted measures such as foreign direct investment (FDI) flows and indices for capital account liberalisation. Furthermore, the globalisation index of the Swiss Economic Institute (KOF) has emerged as the most popular hybrid economic globalisation measure. Our study discusses how these different openness measures are constructed, and what the advantages and pitfalls of using them are – depending on the research context.

Trends in economic openness

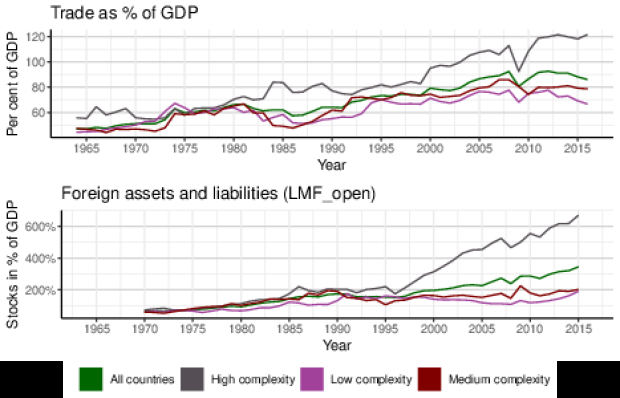

To illustrate what our data set allows for when it comes to descriptive analysis, we show trends of two prominent de-facto openness indicators – one from the trade dimension and the other one from the financial dimension. We classify countries according to their economic complexity, a proxy for the level of their technological capabilities. This is motivated by findings according to which countries with high economic complexity tend to benefit more from economic openness.

Indeed, we observe some substantial differences in de-facto trade openness when considering technological capabilities. Specifically, we find that the trade-to-GDP ratio of high complexity countries started to decouple from the moderate and low complexity countries in the early 1990s. This finding suggests that countries that are technologically more advanced (and are, thus, likely to benefit more from trade) tend to record higher de-facto openness to trade. We can also see that according to de-facto trade openness that trade integration has reached a peak before the start of the financial crisis in 2007/2008. Against the background of changes in trade policy – in particular in the case of the US under president Trump – and the potential repercussions of the COVID-19 crisis on the globalisation process, de-facto international trade integration may be expected to continuously proceed at a much slower pace than in earlier decades.

The one selected measure of financial openness (foreign assets and liabilities to GDP) shown in the figure below exhibits a similar, but even stronger trend than trade-to-GDP. Financial openness of the high complexity group quickly decoupled from the other groups between 1995 and 2000, that is, after the foundation of the WTO in 1994. Since then, the gap between the high complexity group and the other country groups has grown substantially, implying that the integration of financial markets among high complexity countries has proceeded faster than in the rest of the world. Eventually, we observe that the financial crisis of 2007-08 only had a minor impact on financial openness: after a crisis-induced reduction, the level of financial de-facto openness recovered rapidly and continued to grow, which has not been the case for de-facto trade openness.

Sources: World Bank, LMF database, Atlas of Economic Complexity; own calculations.

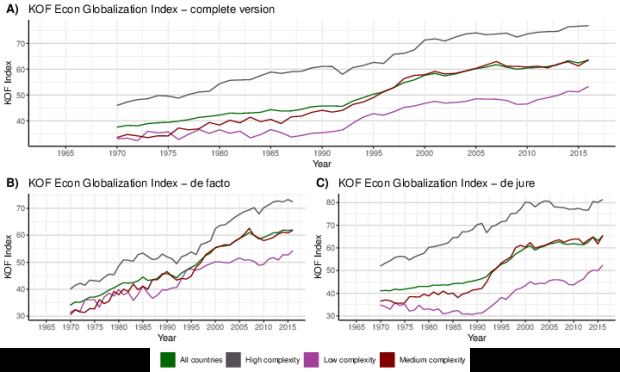

The KOF globalisation index – a hybrid index capturing both the trade and financial dimension – provides a more complete view on the increase of economic openness in previous decades and the plateauing of the economic globalisation process since the global financial crisis. As can be seen from the figure below, the index captures the overall trend of increasing openness from the 1970s to the 2000s, and it indicates different dynamics in the de-facto and de-jure dimension.

Sources: KOF, Atlas of Economic Complexity; own calculations.

The past and future of globalisation

We conducted a correlation analysis of more than 30 openness indicators, which reveals stronger associations among indicators belonging to the same type (e.g. trade de-facto measures such as trade/GDP typically show a relatively strong relation with other trade de-facto indicators). However, only weak to moderate correlations of indicators can be established across different types (e.g. trade de-facto vis-à-vis financial de-facto). Furthermore, our results indicate that operationalising economic openness for econometric research requires explicit theoretical justifications of the openness dimensions relevant for the research question at hand as well as the available indicators used for capturing these dimensions. Differences in how openness indicators correlate with economic growth illustrate the theory-ladenness of observation, i.e. the assumptions underlying the construction of different openness indicators make an important difference.

Our data set makes a large bunch of relevant trade, financial and overall openness indicators available for future research, and we hope that it will prove useful for many applied researchers working on the socio-economic effects of globalisation. In the context of the current Covid19 crisis, there is substantial interest in how Covid-19 will affect market integration in trade and finance in the years to come. Via an R package, we will provide regular data updates on all the compiled openness indicators, which should allow for tracking the development of different facets of economic openness in the process of gaining a better understanding of the impact of the current crisis.