Peril and possibility: What a US-Iran deal needs to give it any chance at success

25 April 2025

Economic hardship and military pressure have brought Iran to the negotiating table. Though only a comprehensive agreement addressing all problems between Iran and the US could bring about stability and economic development, it is unlikely to happen

image credit: unsplash.com/Mim Sourena

By Mahdi Ghodsi

The return of Donald Trump to the White House has redefined the contours of US-Iran relations. In a striking turn of events, his administration has succeeded in pressuring Iran back to the negotiating table, an outcome many had considered improbable after years of escalating tensions, sanctions and strategic mistrust. After a round of retaliatory threats exchanged between President Trump and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, indirect talks were initiated in Muscat, the capital of Oman. Two recent rounds of negotiations – first in Muscat on 12 April 2025, and then at the Omani Embassy in Rome on 19 April 202 – signal not only renewed diplomatic engagement but also the potential for a broader recalibration of relations. However, the challenges remain formidable – and any sustainable agreement must extend beyond nuclear containment to address Iran’s economic crisis, regional behaviour and human rights record.

The driving forces: US strategic interests and Iran’s economic crisis

There are two reasons why negotiations have resumed. First, Trump’s renewed engagement is anchored in regional priorities. His invitation to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as the first foreign prime minister to the White House on 6 April 2025 underscored the importance of Israel and the Middle East in his foreign policy. Iran, with its support for military proxies like Hezbollah, the Houthis and Hamas, has long been viewed as a regional destabiliser. But Trump’s primary concern is Iran’s nuclear capabilities, which could allow the country to build an atomic bomb – a scenario that the US and Israel want to avoid at any cost. In addition, the Europeans, Russians and Chinese have no interest in seeing a nuclear-armed Iran, which is why they played an important role in negotiating the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action ( JCPOA) nuclear agreement. Since the US withdrew from the JCPOA in May 2018, Iran has moved closer to becoming a threshold nuclear state, without complying with the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) – an international agreement meant to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons – or allowing full monitoring by the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

From Washington’s perspective, the nuclear issue is not just a security challenge; it is an opportunity. A deal with Iran could provide Trump with a foreign policy win, reduce the risk of nuclear proliferation in the region, and bolster US alliances – all while appealing to his domestic base.

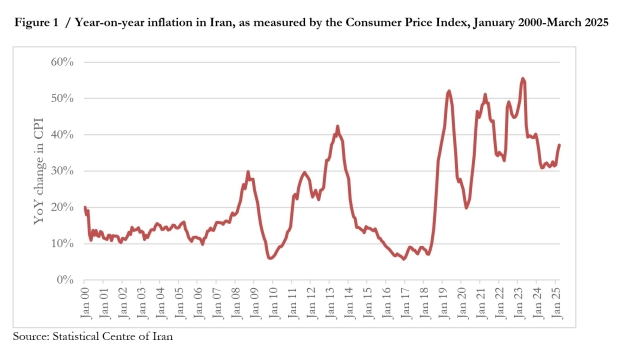

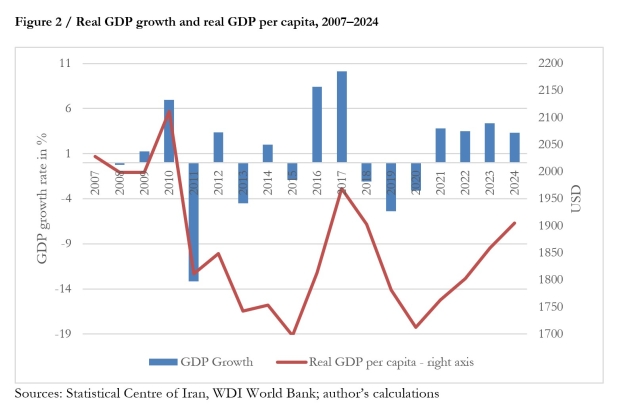

Second, at the heart of Iran’s return to negotiations lies a severe economic collapse. Since 2019, average annual inflation has hovered around 40%, compared to just 19% on average over the previous 35 years (see Figure 1). The rial, Iran’s currency, has experienced extreme depreciation, while sanctions have choked off oil revenues, foreign investment and financial connectivity. The Iranian economy has experienced substantial contraction in per capita terms since international sanctions intensified in 2011 (see Figure 2). The formal labour market cannot absorb Iran’s young, educated population, and nearly 60% of the population lives below the poverty line in terms of calories recommended for a healthy nutrition. Sanctions have made essential imports expensive or inaccessible, further fuelling public frustration.

Figure 1 / Year-on-year inflation in Iran, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, January 2000–March 2025

Figure 2 / Real GDP growth and real GDP per capita, 2007–2024

Note that GDP per capita is calculated as constant 2016 prices with recent USD reported by the Central Bank of Iran at USD 1=IRR 572,133 on 24 April 2025.

The Iranian state is losing legitimacy. The regime’s crackdown on protests, its brutal human rights record – the Islamic Republic has executed 972 individuals in 2024 alone – and its unwillingness to permit political pluralism or even moderate dissent have left it increasingly disconnected from a society that is both disillusioned and digitally empowered. The return to negotiations with the US, therefore, is not merely a concession to US pressure, but a calculated attempt by the regime to buy time and secure resources amid profound internal uncertainty. Public protests, particularly the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ movement, have made it clear that people no longer accept the despotic rule and the trade-off between geopolitical ambitions and domestic neglect. Confronted by social unrest, economic decline and military vulnerability, Iran’s leaders are now seeking short-term relief and hoping for long-term survival.

The agreement needs to be comprehensive to become a long-term success

The outcome of the potential agreement must include some key points to be successful.

First, any new deal must provide clear, verifiable and irreversible limits on Iran’s nuclear programme, including full IAEA monitoring and the dismantling of uranium enrichment beyond the needs of a civil nuclear programme. Proposals for joint nuclear operations with the US or Saudi Arabia could serve as confidence-building mechanisms.

Second, a lasting peace must be based on justice and human rights. The Trump administration has a rare opportunity to make democratic accountability a central pillar of its Iran strategy. This includes demanding the release of political prisoners, an end to internet blackouts during protests, and guarantees of basic civil liberties. Such measures are not only ethically imperative, but also politically stabilising. An Iran that respects human rights could help pave the way for a more peaceful region, one in which diplomacy replaces violence and stability is built on justice rather than fear.

Third, the US must demand a reduction in the activities of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps – the regime’s elite paramilitary force and praetorian guard – abroad and potentially initiate a broader regional disarmament initiative. Iran’s support for proxy groups must be curtailed in order to stabilise relations with its neighbours and pave the way for economic reintegration.

Fourth, any sanctions relief must be accompanied by reforms to ensure that funds are used for economic recovery rather than the enrichment of the elite. Ratifying the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force – an initiative of the G7 countries to combat money laundering and terrorist financing – including the Palermo and Terrorist Financing Conventions, would be a constructive first step.

Fifth, at the heart of Iran’s dysfunction lies its political structure. Deep political and institutional reforms must involve curtailing the unelected authority of the Supreme Leader and strengthening Iran’s elected institutions. Without such changes, any economic or diplomatic progress will remain fragile.

A realistic agreement would involve phased incentives. Initial steps could include unfreezing Iranian assets, expanding humanitarian trade and granting limited access to SWIFT, the Western system for inter-bank financial transactions. Subsequent phases might involve reauthorising oil exports and reopening Iran to international investment. In the final stage, if comprehensive reforms are implemented, full diplomatic and economic normalisation could follow. Countries and blocs of countries, such as the EU, Japan, South Korea and the Gulf states, along with institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, could play a key role in facilitating Iran’s reintegration. However, international goodwill will only materialise if Tehran moves beyond its revolutionary posture and engages on issues beyond the nuclear file.

A historic – but fleeting – opportunity

A successful agreement could unlock Iran’s economic potential. Even partial sanctions relief could facilitate trade in key sectors. However, foreign direct investment (FDI) in these areas will require a comprehensive deal that addresses all outstanding issues between the US and Iran. Iran’s energy sector – both fossil fuels and renewables – has vast capacity. The country’s manufacturing base, including the automotive industry, could be revitalised, while its tech-savvy youth have the potential to drive a boom in digital and knowledge-intensive services. However, monopolistic state foundations and constitutional restrictions remain significant barriers in many sectors, including pharmaceuticals. Without deep institutional reform, Iran will remain trapped – underdeveloped and unstable.

However, the odds remain stacked against a truly transformative, comprehensive agreement that goes beyond the nuclear issues. Iran’s regional behaviour, its authoritarian governance, and the presence of political hardliners in Washington, Tehran, and Jerusalem all complicate diplomacy. Hardliners can sabotage progress, as can domestic crises. Furthermore, the US must avoid repeating the mistakes of the JCPOA. Without bipartisan support in the US Congress, any deal will be vulnerable to reversal. A sustainable agreement must be broad, balanced and enshrined in law.

Thus, this is a moment of both peril and possibility. The fact that the Trump administration has brought Iran back to the negotiating table is already an achievement in itself. However, the stakes are higher than ever. Economic collapse, social unrest, the weakening of regional proxies, and nuclear escalation have brought the Islamic Republic to a breaking point. This moment presents an opportunity to do more than merely contain Iran. It offers a chance to begin reshaping the country’s relationship with the world, supporting the Iranian people, and reducing regional tensions.

However, over his 36 years as Iran’s Supreme Leader, Khamenei has exhibited a deeply entrenched despotism, consistently prioritising hardline Islamic ideology over the well-being, welfare and desires of Iranian society. His policies have brought Iran to a critical juncture, one from which recovery is unlikely without profound and comprehensive reform. Rather than embracing meaningful change, he aims solely to secure the removal of secondary US sanctions to facilitate trade with China and the BRICS+ countries.

However, Trump holds significant leverage at the Islamic Republic’s most vulnerable point – leverage that could be used to push Iran towards a path of reform, potentially empowering Iranian society and contributing to sustainable peace in the region. While the current rounds of negotiations are narrowly focused on nuclear issues, this should not deter us from outlining what a sound and forward-looking policy should entail. As John Kerry, the former US Secretary of State and chief negotiator of the JCPOA agreement, noted in his recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, this is the best opportunity to strike a comprehensive deal with Tehran.