Sailing close to the wind

24 May 2018

The Turkish central bank has hiked rates significantly, but may still need to do more. Political and economic uncertainty will remain high.

By Richard Grieveson

Photo: Yeni Turkish Lira, ccarlstead, CC-BY-NC-2.0

- The Turkish central bank was forced on May 23rd to hike interest rates in order to arrest the collapse in the lira.

- The hike has brought relief for the lira, and significantly reduces the chances of a full-blown crisis in Turkish markets. However, it may not be enough, and we do not rule out more tightening in the near term.

- The lira collapse is damaging in three main ways: it will push up servicing costs on foreign debt in local currency terms, add to already high inflation, and damage the credibility of economic policymaking.

- The general election is only one month away, and appears too close to call. There are still many factors stacked in President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s favour, but the lira collapse has increased the chances of an opposition victory.

- Whoever wins, political uncertainty is likely to remain elevated, particularly if the result is very close.

- We maintain our view that after the election policy will need to be tightened further, and that growth rates during the forecast period will be lower than in 2017.

The Turkish central bank accepted the inevitable on May 23rd, and hiked its late liquidity window lending rate by 300 basis points. The decision came in response to the sharp weakening of the lira. Such has been the scale of the lira sell-off, and the knock-on effects for external debt servicing and inflation, that the central bank had no choice. The lira has faced depreciation pressures for some time, reflecting domestic and geopolitical risk factors, a rising dollar, negative real interest rates, and the widening current account deficit.

The decision to tighten initially calmed the market, with the lira rallying against the US dollar in the immediate aftermath. Moreover, the messaging accompanying the decision to tighten was strong and coordinated. Mr Erdoğan stated that Turkey would 'abide by the global governance principles on monetary policy.' Mehmet Şimşek, the deputy prime minister, tweeted 'it’s high time to restore monetary policy credibility and regain investor confidence'. However, the 300 basis points of tightening may not be enough, and we do not rule out further hikes in the near-term.

Implications of the lira collapse

Before the hike, the lira had lost close to 25% of its value against the US dollar since the start of the year. This has a host of important implications, but we see three as particularly significant.

First, the weakness of the currency has pushed up import costs, adding to already uncomfortably high inflation. Inflation was running at 10.8% year on year in April, more than double the central bank’s 5% target. Among other things, this is eating into real incomes, holding back consumption growth.

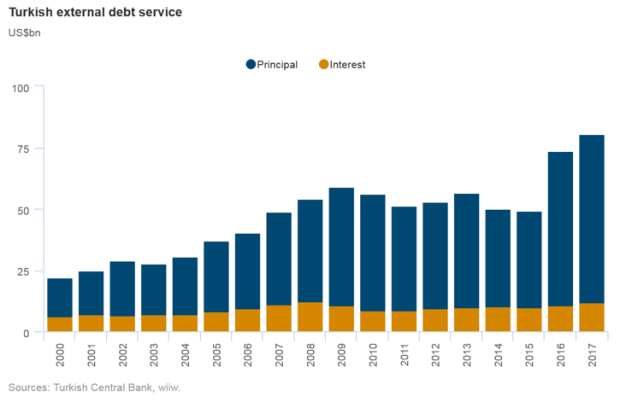

Second, the weakness of the lira has increased the costs of servicing debt in local currency terms. External debt is around 50% of GDP, quite low among countries in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE). However, annual rollover needs are around 20% of GDP, leaving the economy exposed to liquidity risks. Short-term external debt in US dollar terms rose by 14.3% (US$ 15.3bn) year on year in Q1.

Third, the collapse in the lira affects the credibility of policymaking. For weeks, the lira weakened without a central bank response. Mr Erdoğan’s comments in London last week, where he reiterated his view that higher interest rates cause inflation, appears to have particularly spooked the market.

What this means for the election

Turkey will go to the polls for an early election on June 24th. This will be the first poll held under a new constitution granting much greater powers to the president. Opinion polls show Mr Erdoğan far from victory in the first round, while polls for the second round run-off indicate a very tight race.

On the one hand, it would definitely be a mistake to count Mr Erdoğan out, and we see his victory as still the most likely outcome. Mr Erdoğan still has a lot of factors stacked in his favour, including a large and motivated support base, greater media coverage than his opponents, nationalist support related to Turkish military interventions in Syria, and the fact that he has presided over almost two decades of generally rising living standards for much of the population. The result of last year’s referendum on the change to the constitution was already tight, but since then the economy has done well, and employment growth is currently running at around 5% year on year. However, in light of the lira collapse, the chances of an opposition victory have risen. This episode has the potential to cost Mr Erdoğan the election.

Whoever wins, expect continued uncertainty and lower growth

Irrespective of the election outcome, we see a strong chance that political volatility will be high. This would be especially the case if the second round run-off produces a close result and the loser disputes the outcome.

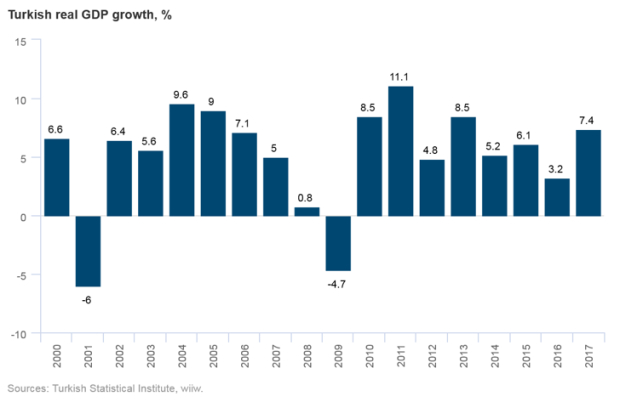

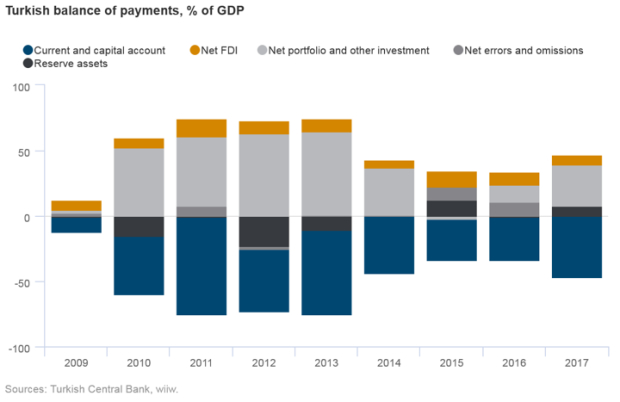

On the economic side, the economy is clearly overheating. Growth has been pushed well above its potential by fiscal and monetary stimulus. Marginal credit to fund higher growth is coming from abroad, reflected in the widening current account deficit and rising external debt. The current policy stance is not sustainable.

The May 23rd tightening of monetary policy will not be enough on its own to address the overheating issue. After the election we expect further tightening of policy, in both monetary and fiscal terms, in order to cool growth. Stimulus probably added around 3 percentage points (pp) to growth last year (1pp on the fiscal side, and 2pp from the credit guarantee fund). Withdrawing this would take growth down to the 4-4.5% range. We expect growth to be roughly in this range in 2018-20.

An outright crisis is not our core scenario, but the risks have increased. We reiterate several factors that will mitigate these risks. First, global monetary conditions remain very benign, with the US Federal Reserve only tightening slowly, and the ECB even more so. Second, the banking sector has quite a good starting position (albeit maybe less so than the headline NPL ratio suggests). Third, the fiscal position is strong, with public debt at low levels.

We also reiterate our view that over the long run, the current Turkish growth model is not sustainable. The current account deficit, in basic terms, reflects a lack of domestic productive capacity and competitiveness issues, and growth rates much above 4% (and much less in per capita terms) need ever more credit and a consequent continued build-up of external debt. Very little of the funding for the current account deficit comes from FDI at present. Over the medium and long term, Turkey will either have to find a new growth model (for example based on attracting more FDI and rises in productivity), or get used to a much lower growth rate than has been the case recently.