Structural reforms: Does easing employment protection reduce unemployment?

14 December 2020

A meta-analysis finds no robust evidence that stricter employment protection leads to higher unemployment. This raises doubts over the policy focus on easing employment protection.

by Philipp Heimberger

photo: iStock.com/Victoria Labadie

When unemployment rates sky-rocketed as a consequence of the 2008 financial crisis and remained high over an extended period of time, policy discourse across Europe soon focused on how ‘structural reforms’ of labour market institutions should be used to bring down unemployment. Suggestions by leading policy-makers that ‘structural’ reforms geared towards easing employment protection legislation (EPL) can help reduce unemployment greatly influenced policy debates in the post-financial-crisis era.

Indeed, several European governments introduced measures to increase the flexibility of existing labour regulations with the goal of making it easier for firms to hire and fire workers, leading to intense debates about the actual impact of such deregulation measures. Obviously, the focus on tackling unemployment by calling for labour market deregulation was not entirely new; it has shaped the policy discourse since at least the early 1990s, when the OECD launched its Jobs Strategy and other international organisations such as the IMF also repeatedly called for more flexible labour regulations.

But is this across-the-board policy focus on strict employment protection as a major cause of high unemployment across countries really justified by the best available empirical evidence? My new study, which has just been published in the journal “Oxford Economic Papers”, provides an answer to this question, and it is a resounding “No”. True, some prominent papers provide empirical support in favour of unemployment-increasing effects of EPL. Other studies, however, contradict these findings by using robustness checks as well as variations in data sources and econometric approaches.

My study presents a “meta-analysis”. This means that I put all the relevant estimates on the EPL-unemployment nexus reported in the literature into one data set and systematically evaluate these estimates using statistical methods. In this context, meta-analysis can be understood as a comprehensive quantitative literature survey. By considering all the various pieces of econometric evidence and fitting them into the bigger statistical picture, I find that the average effect of employment protection on unemployment is zero.

The theoretical effects of employment protection, understood as the set of restrictions on the ability of the employer to utilise labour, are not clear-cut. On one hand, the standard competitive model predicts that employment protection will increase unemployment, as employers are reluctant to hire workers because they fear that these workers cannot be laid off easily. On the other hand, more rigid EPL may increase job retention, as companies lay off fewer employees in the face of high severance pay and procedural costs of dismissal, especially during economic downswings. High employment protection can be a plausible explanation for lower flows both of job creation and job destruction. However, the ex-ante effect of EPL on unemployment remains ambiguous, as EPL affects unemployment duration and worker flows in opposite directions. Understanding the relationship between EPL and unemployment is therefore an important question for empirical research. Existing studies report mixed results concerning the impact of EPL on unemployment.

Measuring employment protection

First of all, it must be clarified how employment protection can be measured. The OECD has developed the most prominent quantitative summary index of EPL, measuring the strictness of EPL using discrete indicators ranging from 0 to 6, where higher index values point to more rigid employment protection. The information used for index computation is mainly compiled from national labour laws. The relevant regulations cover aspects such as procedural inconveniences, notice and severance pay, difficulty of dismissal, costs of collective dismissals, fixed-term contracts, and temporary work agencies.

These regulations are given numerical scores that represent the strictness of employment protection. They are assigned to one of the 21 items in the overall EPL summary index, and the individual index components are then weighted.

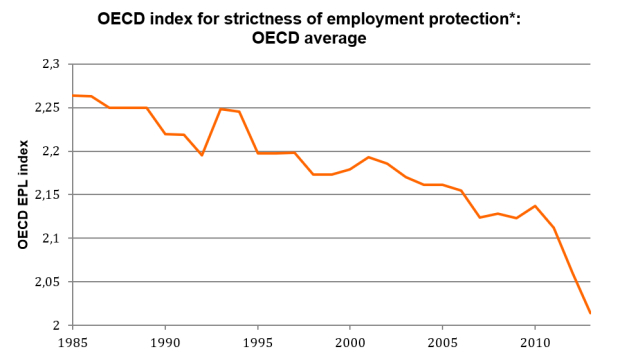

According to the OECD, the strictness of job security regulations for regular employment contracts has decreased on average since the 1990s. After the financial crisis, the Index score is declining, due to deregulation measures in several countries. In Spain, for example, protective regulations for employment contracts were significantly relaxed after 2010 – based on the argument that this would increase the competitiveness of Spanish companies and contribute to a reduction in the sharp rise in the unemployment rate.

Against the background of the high importance of the OECD’s EPL index for policy assessments in respective member states, the construction of the EPL index has been subject to a significant amount of criticism; e.g. deciding individual scores can be seen as arbitrary, and choosing the weights for sub-components of the index has a profound impact on the overall results. Notwithstanding such points of criticism, the OECD’s EPL index remains by far the most prominent approach to quantifying EPL.

The Economic Freedom of the World Index (EFWI) contains sub-indicators on the strictness of hiring and firing regulations that have also been utilised in some of the relevant empirical studies. The EFWI includes data based on surveys and expert panels, in addition to information compiled from legal provisions. Furthermore, several econometric papers on the EPL-unemployment relationship have made use of survey-based measures of the strictness of employment regulations, i.e. they do not collect information from legal provisions but instead construct indices that are exclusively based on surveys of managers and experts that were asked about their assessment regarding the strictness of hiring and firing regulations.

The effect of EPL on unemployment

What do existing studies tell us about the effect of employment protection on unemployment? And what factors contribute to explaining the differences in reported findings? To answer these questions, I conducted a quantitative survey of 75 relevant English-language econometric studies by analysing the effects of employment protection on unemployment rates reported in these studies.

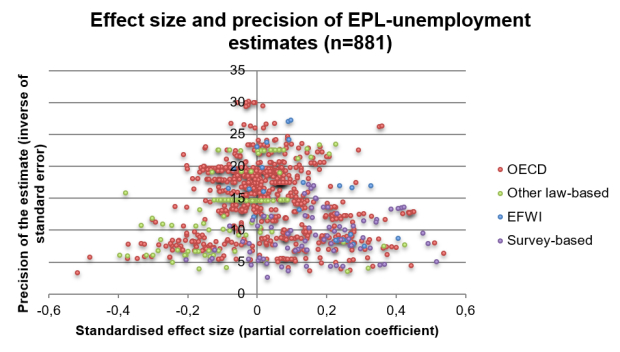

If one evaluates the more than 850 individual results that I collected for the meta-analysis, the first thing that becomes apparent is that the estimates are relatively widely scattered (see the figure below). There is mild publication selection bias in favour of reporting unemployment-increasing effects of employment protection. However, once we correct for this bias, the (precision-weighted) average effect is zero. Importantly, the choice of the EPL variable matters: estimates that use survey-based EPL variables report significantly stronger unemployment-increasing effects than estimates using EPL indices based on the OECD’s methodology, where the latter mainly relies on quantifying relevant information from legal provisions.

One potential explanation is that the managers and experts that are asked about their assessment of the strictness of labour regulations provide answers that depend on the state of the labour market: when unemployment is higher, they tend to see labour regulations as more rigid; and when unemployment is lower, they assess EPL to be less stringent – so that there is a strong positive relationship between survey-biased EPL variables and unemployment rates. Given the well-known problems of survey-based quantification due to potentially biased responses by survey participants, findings of an unemployment-increasing effect of survey-based EPL variables should be reviewed critically. This is important, since some prominent papers that have received hundreds of citations are still regularly cited, sometimes in order to support calls for easing employment protection.

It is important to point out that close to 90% of all the relevant estimates on the EPL-unemployment nexus reported in the literature quantify EPL by using information from national labour laws. Although the construction of EPL variables based on information from legal provisions comes with its own problems, the overall evidence clearly does not support the view of significant average unemployment-increasing effects of EPL. This main result also holds if we only look at estimates concerning the EPL effects on long-term unemployment.

Implications for policy-making

The meta-analysis reported in my study clearly rejects an across-the-board policy focus on strict employment protection. In general, employment protection seems to be less important as a factor for explaining unemployment than is often believed (for both advanced and developing countries). Evidence-based policy-makers should therefore not give advice as if the alleged unemployment-increasing effects of employment protection had been generally confirmed by empirical research. Furthermore, the construction of different EPL measures should be subject to critical re-examination.

Notably, the findings from the meta-analysis would be consistent with an explanation according to which the effects of employment protection are not universal, as increased employment protection may have different effects on unemployment in different countries or specific time periods. As a consequence, there might be a lot to learn from careful analysis of case studies, which allow for considering details of the institutional and macroeconomic context of the specific country cases at hand.

Unemployment rates across Europe and other parts of the world economy have increased strongly over the course of the COVID-19 crisis. We must expect unemployment to stay high for a prolonged time. Against this background, it is not unlikely that policy-makers will call for across-the-board easing of employment protection in order to bring down unemployment. Based on the empirical evidence from my meta-analysis, pushing for an easing of employment protection cannot be seen as a viable strategy for reducing unemployment after COVID-19.

Note: Translated and adapted from a column that first appeared in “Makronom”. The original article is here (in German).