The EU should stick with the Iran deal

14 May 2018

The US withdrawal from the JCPOA is a mistake, and will only strengthen the hand of hardliners in Iran. The EU should try to stick with the deal.

By Mahdi Ghodsi

- US has unilaterally withdrawn from the JCPOA.

- The political fallout is likely to be significant from the Iranian perspective. Hardliners in Iran will be emboldened.

- The economic fallout will also be important and negative. The domestic economy is already suffering, although Iran’s recent diversification of its trade and FDI will help to cushion the blow.

- An EU withdrawal would make things even worse for all parties. Sticking to the deal is a chance for the EU to step up and be a global player.

On 4 May 2018, President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the US from the JCPOA with Iran. This happened despite the regular inspections of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) of Iranian nuclear sites, which had certified Iran’s compliance with the 2015 deal. Many experts in the field and European allies of the US had made extensive efforts to convince Mr Trump to stay in the deal, arguing that no better alternative could possibly replace it.

The conditions under which the JCPOA was signed, during the tenure of previous US president Barack Obama, were quite different. On the one side, Iran – fearing a serious economic breakdown – was attempting to alleviate sanctions pressure. Meanwhile, the EU and the US were looking for a peaceful and long-term diplomatic solution with Iran. However, Mr Trump believes that by nullifying the JCPOA he can achieve a “better” deal.

Why he did it

Attempting to concretely ascertain Mr Trump’s motives is not always straightforward, and the decision to withdraw from the JCPOA is no exception. Broadly, we see six reasons for the move. First, Mr Trump’s decision appears to have partly been based on intelligence provided by the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that Iran lied about nuclear weapons before the deal. Second, Mr Trump was known to be unhappy with the sunset clause of the JCPOA, which indicates that some of restrictions imposed on Iran’s nuclear program will expire in 2025 . Third, Mr Trump wanted inspections of Iranian facilities suspected of nuclear activities to be permitted (1). Fourth, Iran’s military and advisory support to the Assad government in Syria, Hezbollah (a strong political party controlling militia in Lebanon), Houthis rebels in Yemen, and in general alleged role as a sponsor of terrorism. Fifth, a desire to show solidarity with US allies in the region, especially Saudi Arabia and Israel.

A sixth possible reason is a desire for regime change in Iran. This has been stated by Mike Pompeo, the new US secretary of State, several times, and has been given even greater impetus by the appointment of John Bolton as National Security Advisor. Mr Bolton is closely linked to an Iranian political opposition and a militia organization called the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (MEK). He believes that a revolution is plausible in Iran if sanctions depress living standards.

Claims generally unfounded

Few if any of these reasons stand up to much scrutiny. First, the claim that Iran lied about its programme was later rejected by Federica Mogherini, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. On 1 May 2018, the IAEA said in a statement that “although some activities (in the production of nuclear material) took place after 2003, they were not part of a coordinated effort.” Second, while the JCPOA agreement was envisaged for the next 10-15 years, it does not suggest that Iran will be allowed to make a nuclear bomb afterwards. Nullifying the deal now would immediately enable Iran to build a nuclear bomb, and without inspections. Third, based on the deal, the IAEA can inspect any suspected facilities in Iran. On March 5th, Yukiya Amano, IAEA Director General, emphasised Iran's compliance with the deal in all respects. Fourth, following the US withdrawal from the agreement, Iran will likely be even more aggressive in supporting allied groups in the region, and threatening the interests of the US and its allies.

Political and economic consequences for Iran

The political fallout is likely to be significant from the Iranian perspective. Pushing for regime change is a very dangerous game. Another situation like Syria, or a non-democratic regime like that in Egypt and Libya, could emerge. Moreover, hardliners in Iran could now be convinced that a nuclear weapon will give them a bargaining chip in response to the US, particularly as this appears to have worked in the case of North Korea. Mr Trump’s decision has given hardliners within Iran the upper hand. They can now push their agenda and persuade Iranians that overall US policy regarding Iran was only a deceptive conspiracy to effectively halt Iran’s atomic activity by cementing its sophisticated nuclear facilities and by then exporting almost all of its enriched Uranium and heavy water.

The economic fallout will also be negative, and the domestic economy is already suffering. Unrest and protest on the streets of many cities in January 2018, and a very sharp depreciation of Iran’s currency since March 2018, are two recent indications of this. With the ongoing depreciation of currency, Iranians have become much poorer, and due to dollarization, Iranians have rushed to convert money into foreign exchange. This in turn results in a reduction in investment in the productive sector, and further economic downturns.

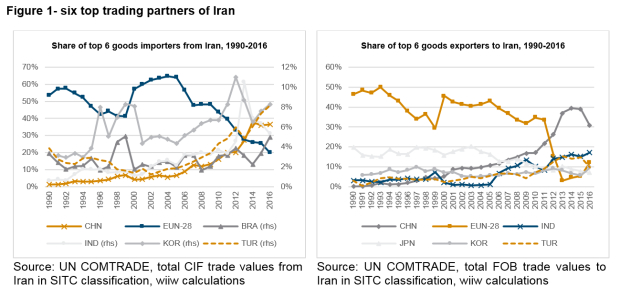

The implications for external trade could also be significant, although Iran has managed to diversify its export markets in recent years, which will cushion some of the blow. After the EU introduced sanctions regarding Iran’s nuclear programme on 23rd March 2012, Iran’s total exports dropped by 32%, which also resulted in a large recession in 2012-2013. Following that, however, China, India, South Korea, and Turkey gradually gained a greater share in Iran’s trade. Because Iran was cut off from SWIFT transactions, it started to barter with these trading partners. For instance, in 2012 Iran started to import gold and precious metal from Turkey and the United Arab Emirates, worth around 16% of its total imports.

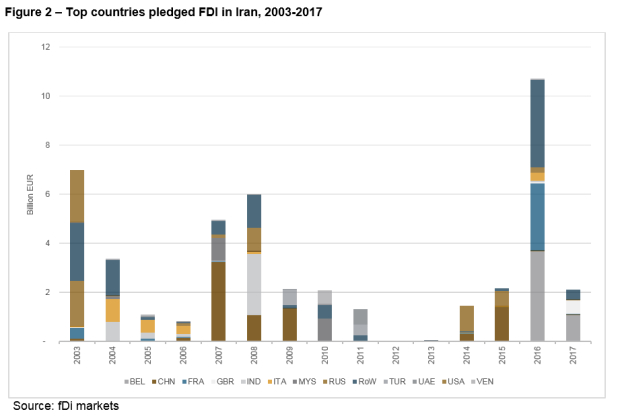

Foreign investment may also be affected, although again here Iran has been fairly successful in diversifying the sources of inflows. As the US did not initiate a trade or investment relationship (except for Boeing which will be most probably stopped) with Iran after the sanctions were lifted, its withdrawal from the deal might not have any significant impact on Iran’s economy. However, US sanctions will have serious consequences for non-US companies doing business with Iran if no counter solution is found. Because of sanctions, no Greenfield investment project in Iran was announced in 2012. However, large investment projects were pledged after the deal (EUR 10.7 bn of projects (3% of GDP) were announced in 2016), but fearing US penalties they have not yet been fully realised. Iran has also made efforts to diversify the source of its inward foreign direct investment more to the East in order to avoid vulnerability against sanctions (Figure 2). Large investment projects in infrastructure have come from Chinese, Indian, and Korean firms.

The return of sanctions would also hamper efforts to achieve more fundamental reforms of the Iranian economy. Engagement with the international community instead of isolation could help Iranian society, the economy, and the government to evolve during a reform phase. Iran still needs a lot to reform in its economic, social, and political spheres. Iranians understood the benefits that further international engagements might bring them. For instance, membership of the WTO would ensure transparency in the implementation of trade policy measures and reduction of corruption at the border, something that Iran badly needs. In addition, connection to SWIFT transactions and the international financial system, requiring Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) frameworks, is another example of integration into the global economy. This could extensively reduce money laundering activities in Iran. Iran accepted international law by signing the JCPOA, which could make Iran more reliable in further engagements with international partners.

The EU now has a very important role to play

The US is still important, but is not the only game in town. Iran has for some time sought better ties with the EU, which already has brought clear progress. It has also established better relations with two other signatories of the JCPOA, Russia and China. Iran has already gained observer status in the Eurasian AML/CFT group, and it is expected to sign a free trade agreement with Eurasian Economic Union. Furthermore, investment projects pledged by Asian companies indicate that Iran will continue undertaking its economic and financial reforms in order to get in line with international regulations.

The role of the EU now looks to be particularly important from the Iranian perspective. Talks will continue with the EU for now. However, the EU is itself facing pressure from the US side with Mr Trump’s “America First” rhetoric, specifically in trade, with the Trump administration having imposed new tariffs on the imports of steel and aluminium (the EU has been granted a temporary reprieve). Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, tweeted “Policies of Donald Trump on Iran Deal and trade will meet a united European approach. EU leaders will tackle both issues at the summit in Sofia next week.”

An EU withdrawal from the deal would be a mistake. More than one and a half decades of diplomacy would be destroyed, and Iran would be free to act as it desires by withdrawing from the NPT Safeguard Agreement, as it did once before in 2005. After the US withdrawal from the deal, Mr Rouhani reiterated Iran’s commitment to the deal without the US, and asked his diplomats to negotiate the possibility of continuing it with other signatories. However, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran who has the final word, is sceptical about European powers remaining in the deal. Most importantly, he warned that Iran may restart its nuclear program if European signatories of the JCPOA also pull out of the deal.

Instead, the EU could push for further negotiations with Iran, to find strategies to counteract US sanctions. A potential EU strategy (without the US) would hinder hardliners in Iran in their attempts to gain influence. A possible solution could be implementing a regulation similar to a previous EU Council Regulation that blocks extra-territorial legislation by a third party, which could then be used to protect EU firms doing business with Iran via an application to the WTO dispute settlement process. Other contingency measures are listed by the International Crisis Group here.

A crucial time for Iran

To secure goodwill and support from other international partners such as the EU, Iran needs to also show its intentions to reform its social, political, and economic frameworks. Having the world’s strongest power as its enemy does not mean that Iran could suppress freedom in its society, one of the main factors in which caused the collapse of Pahlavi Imperial State of Iran. For instance, freedom of speech has recently been violated by filtering Telegram messenger, which is just a means of communication. For eight years, two political leaders and the wife of one of them have been under house arrest without any judicial indictment. Journalists often find themselves in court, and some die in prisons. The hijab is still mandatory for women, and they cannot watch football in stadiums. Iranians, with more than 3000 years of civilization, are mature enough to understand that insults against others and the chants of death to other nations could damage their dignity and image in the world.

(1) Under the terms of the deal, inspectors are allowed to visit military facilities suspected of being involved in the development of nuclear weapons, but with 24 days’ notice.

Photo: Dr. Hassan Rouhani; Credits: Asian Society, CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0