The ‘Tariff Man’ Strikes Again: The Second Round of Trump Tariffs in Historical Perspective and Their Potential Global Impact

03 February 2025

Trump’s new tariffs on imports from Mexico, Canada and China will likely cause significant short-term reductions in trade. While the US may face inflation, Canada and Mexico will experience output declines

image credit: unsplash.com/Pat Whelen

US President Donald Trump launched an unprovoked trade war on 1 February 2025, which is set to take effect on 4 February. The executive order imposes a 25% tariff on all exports from Mexico and Canada, with the exception of Canadian oil and energy products, for which the tariff rate will be 10%. The stated objectives of these tariffs are to curb illegal immigration, reduce fentanyl trafficking across US borders with Canada and Mexico, and shrink the US trade deficit. Additionally, a 10% tariff increase on Chinese exports to the US has been introduced, ostensibly for similar reasons. These new tariffs are in addition to existing ones, and further tariff hikes against the US’s top trade partners are expected in the event of retaliation.

The Canadian government responded immediately with retaliatory tariffs of 25%, mirroring the US measures. However, in the first phase, only about 20% of US imports to Canada will be affected, with the remaining tariffs set to take effect after three weeks. Meanwhile, Mexico and China are still weighing potential countermeasures. In the past, President Trump has also threatened the EU with tariffs, raising concerns that a global trade war may be imminent.

The newly announced tariffs are expected to have a major impact on industries heavily dependent on North American cross-border trade, particularly the automotive, food production and construction industries. US automakers could face declining sales due to higher vehicle costs, potentially giving South Korean and Japanese competitors a market advantage. Similarly, the agricultural sector is concerned about disruptions to food imports and exports, with the risk of retaliatory tariffs affecting US farm exports.

While the Canadian oil industry was spared the highest tariffs to prevent sharp increases in fuel prices for US consumers, the broader trade measures are expected to remain in place until the immigration and drug crises are resolved. However, they are likely to face legal challenges in the US Congress and courts. Additionally, Trump combines trade pressure with far-fetched claims of Canada becoming the 51st US state.

Already during his first administration, Donald Trump introduced a series of protectionist trade measures targeting multiple countries, most notably China. In January 2018, he imposed 30-50% tariffs on solar panels and washing machines. This was followed in March by 25% tariffs on steel and 10% tariffs on aluminium, initially affecting most countries and covering more than 4% of US imports. By June, these tariffs were extended to the EU, Canada and Mexico. Separately, a series of escalating tariffs on Chinese imports triggered retaliatory measures by China specifically in the areas of critical raw materials that are necessary inputs in chip and battery production.

Although some trade barriers were already erected starting with the Obama administration, President Trump has effectively ended decades of US advocacy for free trade. Looking further back, the current radical tariff hikes evoke comparisons to the last US-led global trade war, which was initiated by a series of three Republican presidents who governed from 1921 to 1933: Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. The Emergency Tariff of 1921 was introduced in response to plummeting agricultural prices after the First World War. This was followed by a significant escalation with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which raised US tariff rates to an average level of 25% (Figure 1). The US trade restrictions provoked a global trade war, which, combined with the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, arguably contributed to the rise of fascism in Europe and Asia.

Figure 1 / Average US tariff rates, in %, 1827-2022

Note: From 1827 until 1994 bilateral customs duties-to-imports ratios; from 1995 onwards weighted average tariff rates.

Source: CEPII TRADHIST v.4, WITS, own calculations.

How will the second round of Trump tariffs impact the global economy? While general equilibrium trade models typically predict modest long-term effects as economies adjust to the new normal, partial equilibrium models can better capture the immediate and disruptive short-term impacts of tariff hikes, as they largely disregard second-round effects. To assess these short-term consequences, we apply the partial equilibrium Global Simulation Model (GSIM) to the current situation for the US, Canada, Mexico, China, Japan, the UK, the EU and the aggregated rest of the world.

In our model, goods trade flows are based on UN COMTRADE 2023 import and export data in USD. Domestic trade is approximated using 2023 GDP data from the WDI database. Initial tariff rates are taken from the 2022 ad valorem simple average rates in the WITS database. Following the outlined scenario, we assume that US tariffs will increase by 25 percentage points (pp) on Mexico, 20 pp on Canada, and 10 pp on China. Additionally, we account for an immediate retaliatory tariff increase of 5 pp by Canada on US imports. To ensure a conservative estimation of trade effects, we apply a composite demand elasticity of -1, an industry supply elasticity of 1.2, and an elasticity of substitution of 4 along their lower bound values in earlier research.

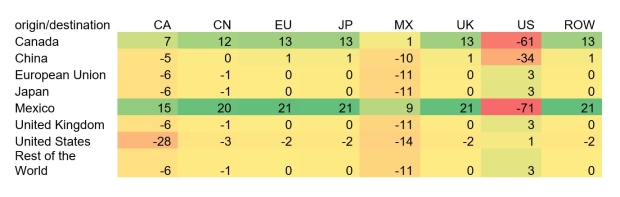

The projected trade impacts on Mexico and Canada are substantial. According to the model, Mexican exports to the US could decline by approximately 70%, while Canadian exports to the US may drop by around 60%. Chinese exports to the US are also expected to decrease by more than a third (Table 1). However, the model predicts that Canadian exports to other countries could rise by about 10% on average, while Mexican exports to non-US markets may increase by approximately 20%. Meanwhile, the US is expected to experience a decline in exports to all other regions alongside a rise in imports from the EU, Japan, the UK, and the rest of the world, as domestic price levels are likely to increase as a result of the trade war. It is important to emphasise that these trade shifts reflect short-term effects, which are likely to be much stronger than longer-term adjustments. Factors such as exchange rate fluctuations and supply chain realignments – which are not considered in this analysis – could mitigate some of these impacts over time. A sharp appreciation of the US dollar could even have a substantial short-term impact.

Table 1 / Simulated trade war effects in terms of percent change of trade quantities

Source: Own calculations using the partial equilibrium GSIM model.

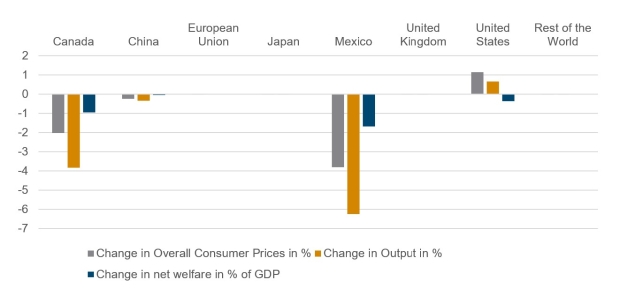

The US is expected to experience an additional inflation surge of over one pp (Figure 2). Even President Trump has acknowledged this possibility in an effort to prepare the American public for some economic hardship. At the same time, consumer prices in Canada and Mexico are projected to decline by approximately 2% and up to 4%, respectively, as some goods originally destined for export are redirected to local markets. Conversely, while US output is expected to grow by slightly more than half a pp, Canada and Mexico are likely to face output declines of around 4% and 6%, respectively. The effects on other countries are expected to be negligible. Overall, all parties involved in the trade war are projected to experience net welfare losses, measured as the combined effect of producer surplus, consumer surplus and tariff revenue. Mexico, as the most vulnerable economy in this scenario, could see a net welfare loss exceeding 1.5%, while Canada may lose nearly 1% and the US less than 0.5%. Although US manufacturing firms and workers may benefit, overall consumer losses are likely to outweigh these gains. For China, the overall impact is expected to be minimal.

Figure 2 / Simulated trade war effects in terms of CPI, output and net welfare

Source: Own calculations using the partial equilibrium GSIM model.

The above analysis suggests that while a trade war would generally leave everyone worse off, the US manufacturing sector might temporarily regain some ground. However, President Trump’s bilateral approach is unlikely to alter the overall production and trade patterns of the US. According to American economist Michael Pettis, permanently eliminating the US trade deficit requires more systemic and structural measures. As he argues, the previous laissez-faire, free-market strategy was at the heart of US deindustrialisation, as the economy was heavily influenced by the aggressive mercantilist policies of trade partners like Germany and the EU as well as by China’s real exchange rate policies. These factors led to an influx of forced excess savings into the highly liberalised and deep US capital markets, driving up the value of the US dollar and, in turn, causing large trade deficits and a decline in manufacturing. Similarly, while President Biden’s fiscal and industrial policies promoted growth in key sectors and supported re-industrialisation efforts, they failed to drive a broader, systemic transformation. The most effective way for the US to reduce its absorption of global trade and capital imbalances would be to limit foreign access to US financial markets – potentially by imposing taxes on financial inflows. This approach would encourage lower savings rates by stimulating domestic demand in China and boosting investment activity in Germany and other European economies, ultimately improving their growth performance.