Theresa May calls snap UK parliamentary election

19 April 2017

The Conservatives will significantly increase their parliamentary majority. This could mean a slightly “softer” Brexit, but will not be a game changer. A commentary by Richard Grieveson.

Photo: William Murphy, CC-BY-SA 2.0

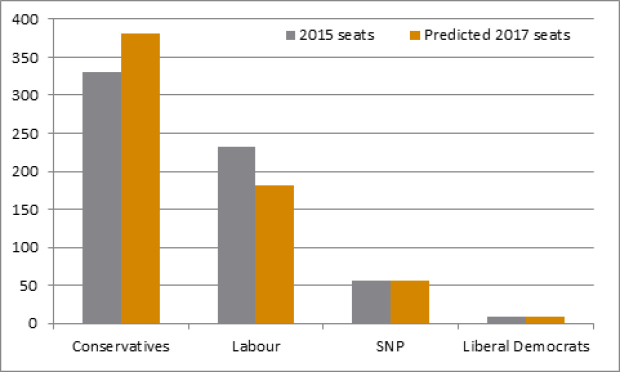

UK Prime Minister Teresa May’s call for an early election will be confirmed by parliament today. The main opposition Labour Party has already announced that it will vote in favour. Opinion polls indicate that the Conservatives will win a much bigger majority (currently it is just 17 seats).

A convincing Conservative victory would probably make a truly hard Brexit less likely. Ms May has been wary of backbench rebels, given her slim parliamentary majority. A bigger majority would allow Ms May to adopt a slightly softer tone with regards to the EU. It would also increase her insurance policy when the stark negative aspects of Brexit—such as further UK payments into the EU budget and tougher conditions for exporters to EU markets—start to become apparent. The prime minister was probably (understandably) cautious about facing an aggressively hostile tabloid press and some hard-line backbenchers in this context with such a slim majority.

The rise in the value of sterling after the news broke suggests that the market now expects a softer Brexit. However, even a huge Conservative majority would not be a game changer. A fairly hard Brexit is still the most likely outcome of negotiations. Ms May was at best only a reluctant supporter of the UK remaining in the EU, and plans to take the UK out of the single market and customs union. She has repeatedly stressed that she wants to regain full control over immigration to the UK, and to end the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice. A convincing victory for the Conservatives will probably make it harder for the House of Lords to hold up legislation related to Brexit.

A transition deal for Brexit will be much easier if Ms May wins a large majority. Many hardliners in the Conservative party do not want a transition deal. However, Ms May believes that such a strategy is reckless. By holding an election now, she is ensuring that the next one will not be until 2022, rather than 2020. An election in 2020 would have been immediately after the conclusion of the two-year Article 50 negotiations in 2019, something that Ms May appears keen to avoid. In terms of a post-2019 transition deal, this means that the government has more time before next going to the polls.

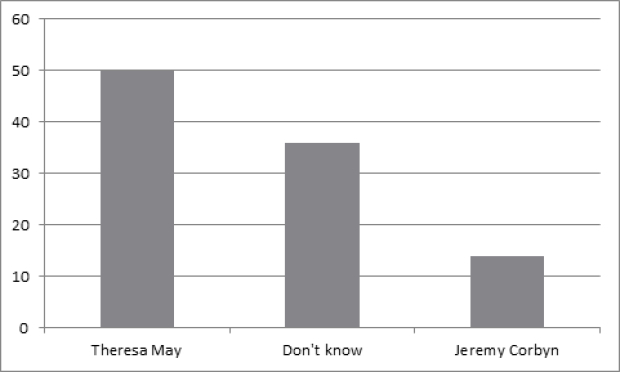

The Labour Party is facing a heavy defeat. A strong Labour Party led by a feasibly electable leader, in concert with the Liberal Democrats on an avowedly anti-Brexit ticket, represents the best (albeit very slim) chance of the UK reversing its decision to leave the EU. However, this will not happen. Labour’s election leadership rules mean that they are stuck with Jeremy Corbyn. Mr Corbyn is hugely unpopular with the electorate, and even many Labour voters do not see him as a realistic candidate for prime minister. Ms May’s speech announcing the election implied that she sees the Liberal Democrats—the only national party unambiguously against the UK leaving the EU—as the main threat.

Ms May remains popular but her credibility could be gradually eroded. Until very recently, Ms May and those close to her were strongly ruling out an early election. Her spokesman said on March 20th: “It isn’t going to happen; there is not going to be a (early) general election”. Meanwhile, only last month, her government changed course on a proposed hike in national insurance contributions. Ms May’s reputation as an unusually principled politician who sticks to her promises is being lost.

In some ways, this is a gamble by Theresa May. First, with the Labour Party not seen as a credible opposition by swing voters, there is a risk that many will assume a strong Conservative win and simply not turn out to vote. Second, Ms May’s Brexit negotiating position will be heavily scrutinised on the campaign trail, which could force her or her ministers into public commitments which could later restrict their negotiating room. Third, many Conservatives are uneasy that a large number of voters could cross traditional party lines to vote against leaving the EU. This is a particular issue for Conservative members of parliament facing strong Liberal Democrat candidates in their constituencies (and a reason that the Liberal Democrats may well do significantly better than headline polling numbers suggest).

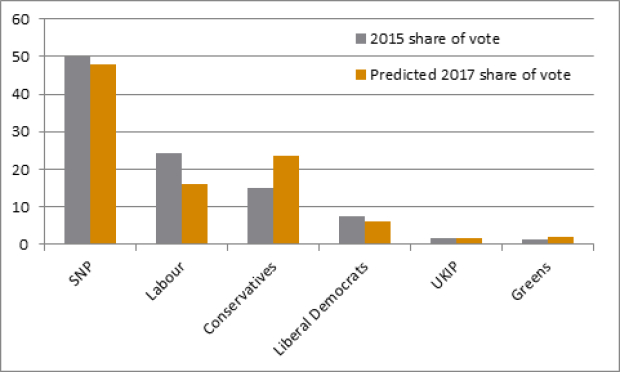

The gamble is particularly risky with regard to Scotland. Having told Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon that there was no case for a second referendum on independence following the Brexit result, and accusing her of stoking instability, Ms May now risks being seen by many Scottish voters as guilty of the same thing. Opinion polls suggest that support for the SNP has declined, that a second independence vote held now would produce the same result as the first, and that Scots do not want a second referendum now. However, the SNP remains by far the most popular party in Scotland, and the opinion polls on independence are far too close for comfort from the perspective of unionists. While the Conservative vote share has been rising strongly in Scotland, this largely reflects gains from Labour rather than the SNP.