Three years of full-scale war in Ukraine: What would a dictated peace mean?

24 February 2025

It would crush Ukraine’s sovereignty and economic future, undermine Central Eastern Europe’s FDI-driven growth, and end Europe’s peace dividend for good. Russia, meanwhile, could see economic gains in the medium term and become less dependent on China

image credit: unsplash.com/Vony Razom

By Richard Grieveson and Olga Pindyuk

- Whether or not a dictated peace will really happen anytime soon is very much an open question, most importantly because Russia will almost certainly insist on receiving a lot more Ukrainian territory.

- For Ukraine, the consequences would be nothing short of a nightmare. Reduced to a de facto vassal state of Russia, the country’s hopes for meaningful reconstruction, a prosperous economic future, EU membership and full national sovereignty would be crushed.

- It is possible that Ukraine could become some kind of ‘colony’, whose raw materials would be exploited by both Russia and the United States.

- The EU members in Central and Eastern Europe would see their FDI-driven growth model undermined, with negative effects on growth, as foreign investors would think twice about investing without a credible US security guarantee.

- For the ‘older’ EU member states in Western Europe, an end of the US security guarantee for Europe would exacerbate already ballooning public deficits. This would most likely necessitate cuts in social spending and the welfare state as well as increased borrowing, deepen domestic political divisions and further alienate electorates.

- Russia, by contrast, stands to benefit economically in such a scenario, even though it would need to subsidise the newly occupied territories for decades to come.

- While Russian growth may initially slow due to reduced public spending on soldiers’ salaries and compensation, the medium-term outlook could improve with the lifting of US sanctions.

- A rapprochement with the United States could also reduce Russia’s dependence on China.

The anniversary of the third year of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine comes at a time when Ukraine’s prospects have rarely looked so bleak. While the war may well now come to an end more quickly than would have been the case if Biden had won a second term, any peace will not be on terms favourable to Ukraine. The risk of a ‘dictated peace’, where Russia and the US agree on a Yalta-style deal and then present it to Ukraine as a fait accompli, are non-negligible.

The new US administration has been quick to make its position clear. US Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth said in Brussels that the US will prioritise its own borders and its strategic rivalry with China. In a speech at the Munich Security Conference, which revealed raw contempt for many mainstream European politicians, US Vice President JD Vance made it clear that the current administration does not share many values with its European allies. By talking directly to Russia in Saudi Arabia without involving Ukraine or Europe, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has de facto recognised Russia as having a legitimate sphere of influence in a world of great power politics. The US has already made some of its positions clear: Ukraine will not join NATO, and the US will not provide security guarantees to Ukraine after the war.

Although much remains uncertain, it is clear that, from a Ukrainian and broader European perspective, the world has changed quite dramatically in the last few weeks, and that America’s willingness to be the ultimate guarantor of continental security with very few strings attached is over. This article will look at whether peace in Ukraine in the form envisaged by the US is actually feasible as well as what it would mean for Ukraine, Russia and the rest of Europe if this dictated peace were to actually materialise.

Will it actually happen?

Whether or not this dictated peace will really happen anytime soon is very much an open question. One factor is that Russia will almost certainly insist on receiving a lot more Ukrainian territory than it currently controls. Although Russia formally annexed four Ukrainian regions (oblasts) – Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia – back in 2022, in reality, it only controls the latter three to a partial extent. This particularly applies to Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, whose capital cities are not controlled by Russia (although Kherson was initially captured, Russian troops subsequently withdrew from it). The fact that the Russian army has been slowly but steadily advancing westwards in recent months makes capturing the entire territory of these four oblasts – and potentially more – by military means potentially feasible. Russia feels that it is winning and that time is on its side, which may reduce its incentives to agree to a ceasefire, let alone a peace deal, with the US.

In addition, Russia wants to prevent a democratic and pro-European Ukraine, to reverse NATO enlargement, and to reduce the US presence in Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE). The extent of Ukraine’s future cooperation with NATO will be of crucial importance to Russia. While Moscow will certainly welcome Ukraine’s neutrality – which will very likely be part of the deal – the issue of what Western security guarantees to Ukraine will look like is far from certain.

Admittedly, Trump may agree with some of Putin’s demands, and he may not necessarily see Russia as a US adversary. But Trump is still unlikely to give Putin everything he wants. Trump made a lot of political capital out of the debacle of Biden’s disengagement from Afghanistan, and he will surely be wary about facing a similar situation himself when it comes to Ukraine. However, if Trump does not give in to all of Russia’s demands, it is not clear what Putin’s incentives will be to stop fighting. Given these realities, any dictated peace is unlikely to be imposed anytime soon.

Implications for Ukraine

From what has been announced by Trump’s administration so far, the dictated ‘peace’ deal amounts to a de facto capitulation of Ukraine. America’s recent behaviour has been far from what one would expect from an ally and, in fact, the US looks more and more like an ally of the Kremlin. The suggested conditions imply that the aggressor country, which has invaded Ukraine, will not only escape punishment for its crimes, but will also be rewarded with additional territory (a part of which is currently under Kyiv’s control). Moreover, taking Ukraine’s possible membership in NATO off the table means that the country cannot expect any meaningful security guarantees – and will therefore be left vulnerable to future Russian attacks, which are practically guaranteed once Ukraine’s allies stop providing it with military support. Left to its own defences, Ukraine will likely face the possibility of the Kremlin gaining political control of the country and turning it into a vassal state with a puppet government – similar to Belarus. Furthermore, in addition to being deeply wrong in moral terms, not requiring the aggressor to pay any reparations also means that Ukraine would be deprived of desperately needed resources to invest in the reconstruction and recovery of its economy, which has been badly damaged by Russia.

An alternative option presented by Trump to Zelensky, which would give the US ownership of 50% of all the natural resources and infrastructure in Ukraine, is blatant blackmailing. If Zelensky agrees to this, it will again mean that his country’s struggling economy will be deprived of the funds it needs in the foreseeable future, and that Ukraine will essentially be a US colony that supplies it with natural resources, especially critical raw materials.

Thus, both of the options that Trump has offered to Ukraine are unacceptable to Kyiv. This is hopefully only a ‘negotiation tactic’ of the US president. And, of course, the restoration of the EU-US defence partnership is still possible if the Republican Party can muster the courage to disagree with Trump in an open and impactful manner. For Ukraine, it seems there is no other option left other than to keep fighting against the aggressor while continuing diplomatic negotiations with the US.

Implications for Russia

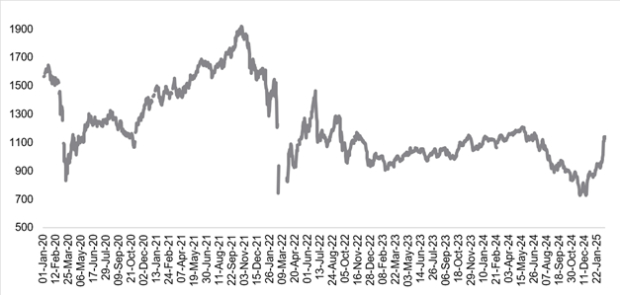

The recent abrupt rapprochement between Russia and the US has triggered a wave of optimism in the Russian financial markets. The stock market has rallied (see Chart 1), government bond yields have fallen, and the rouble has become the best-performing emerging market currency (according to Bloomberg), strengthening by 13% against the US dollar since the start of the year.

Chart 1 / RTS stock price index, 1 Sept. 1995 = 100

Sources: Moscow Exchange, Haver Analytics

Meanwhile, the immediate effect of any peace deal on the Russian economy will probably be negative. The latter has adjusted to massive military spending, which reached some 6.5% of GDP last year but it is set to decline once there is a ceasefire. Although a return to pre-war levels of 3-4% of GDP is not to be expected – if only because of the need to replenish the inventories of weapons and ammunition that have been largely exhausted over the past three years – hefty government payments to soldiers will not be needed to the same extent. According to one estimate from mid-2024, these payments (including monthly salaries to soldiers, one-off payments for concluding a contract with the military, and compensation funds in the case of death or serious injury) totalled some 1.5% of Russia’s GDP and accounted for more than 3% of overall consumer spending. With further hikes in war-related payments in the second half of last year, their importance to the Russian economy has likely increased, meaning that cutting them would represent a negative shock to private consumption and GDP growth.

In the longer term, however, the prospects of a potential lifting of US sanctions and increased economic cooperation with the US would play into Russia’s hands. Of particular importance in this case, from the Russian point of view, would be increased US investments in the energy sector (which was reportedly mentioned during the recent meetings of US-Russia negotiators in Saudi Arabia). The exploration and development of hydrocarbon deposits in geographically and climatically challenging regions of Russia, including the Arctic shelf, is critically dependent on Western technologies, access to which has been restricted by sanctions. Increased cooperation with the US might also have the welcome effect (in Moscow’s eyes) of somewhat reducing Russia’s currently one-sided dependence on China and improve Moscow’s bargaining position vis-à-vis Beijing.

Implications for the rest of Central, East and Southeast Europe and the EU

The initial European response to these developments has been panic. Emmanual Macron organised an emergency meeting of the larger EU member states plus the UK, while a subsequent meeting involved more member states in addition to Canada and Norway. There have been plenty of warnings (since at least the Obama administration) that the US is no longer willing to shoulder so much of Europe’s security burden on its own, but many in Europe seem to have been in denial about this, and even Western Europe’s most capable military powers are still not prepared to beef up their own capabilities. At present, it is obvious that the European members of NATO collectively lack both the ability to act militarily without the US and the means to perform the US security role in Ukraine. What’s more, even if they did have the means, it is not clear that there is the political will and public support to do so. In the end, the EU and the UK will probably have to accept whatever the Americans and Russians decide regarding Ukraine.

For several generations, Europeans have been free riders, depending on the US to guarantee their security. And, despite often lofty rhetoric, they have consistently opted to not take their security into their own hands. This has been a failure not only in the sense of spending enough on defence, but even more so when it comes to proper coordination, including on joint procurement, which could have provided the scale and predictability to develop much more robust arms-production capability in Europe. In effect, shielded by the American security umbrella, generations of Western Europeans have grown up thinking that certain parts of real life (e.g. hard security questions) do not apply to them. But this has now changed.

If a dictated peace were to be imposed on Ukraine, the most obvious economic implication for the rest of Europe would presumably be less eagerness among foreign investors to invest in CESEE. NATO membership and the watertight American security guarantee has been a (and perhaps the) central underpinning of the FDI-led growth model in the region over the past 30 years. Although the US has not said unambiguously that Article 5 is dead, members of the Trump administration have made statements that could be interpreted as implying it. US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth said that the US would not come to the rescue of any NATO force involved in peacekeeping in Ukraine. Famously, in 2024, Trump said that he ‘would encourage [the Russians] to do whatever the hell they want’ to NATO members that do not pay their ‘bills’. According to Romanian officials, a withdrawal of NATO forces from CESEE was one of Russia’s demands at the meeting with US officials in Saudi Arabia. The US security commitment to its NATO allies in Europe, and especially those in CESEE, is therefore in more doubt than it has been at any point in the alliance’s history.

Russian threats have particularly mounted against the Baltics, whose politicians have cited an alleged increase in Russian disinformation campaigns, cyber-attacks, espionage activities, damage to undersea telecom and power cables in the Baltic Sea, and other elements of hybrid warfare. Danish intelligence officials have warned that Russia could be ready to launch a war against the Baltic states within two years of the end of the war in Ukraine, and that it would be more likely to do so if it felt that the US would not activate Article 5. New near-shoring investment, upon which the region has placed so much hope in the wake of the pandemic, would be much less likely to materialise in CESEE in this context.

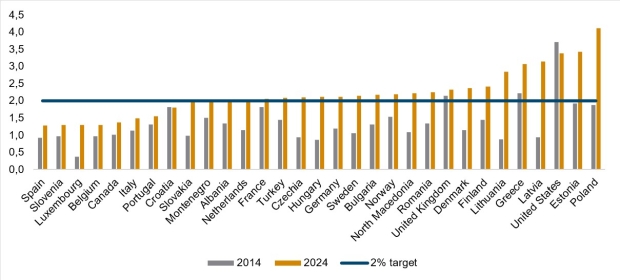

The second implication is that the new US position will intensify the end of the peace dividend. Since the end of the Cold War, NATO members in Europe have enjoyed a (effectively US-financed) peace dividend. They let their armed forces dwindle and used the extra money to fund their welfare states. This has changed, as countries are now racing to increase defence spending relative to GDP. Both Poland and Estonia now spend more on their defence as a share of GDP than the US, a striking change since 2014 (see Chart 2). Although this could foster the expansion of the European arms industry over time, with positive spill-overs (e.g. in innovation) to the rest of the economy, for now it means a squeeze on other areas of spending. This comes at an already difficult time, as these governments are under increased pressure from bond markets and Brussels to reduce their deficits. We calculate that Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia will face the biggest fiscal adjustments across EU-CEE in the coming years, which will weigh on growth.

Chart 2 / Defence spending by NATO members, % of GDP

Source: NATO

A third possible implication is that a dictated peace will lead to a renewed exodus of Ukrainians to other parts of CESEE and onwards to Western Europe. The prospects of a dictated peace without security guarantees may well prompt a renewed (and understandable) sense of insecurity – and perhaps a greater desire to leave – among those who have stayed in Ukraine so far. If this happens, as with the refugees who have already arrived, this could even be a ‘plus’ for the rest of Europe given the persistent labour shortages it faces. Yet, for Ukraine, this will only exacerbate the economic challenges that it will face in the future.

Conclusions

In summary, a dictated peace settlement in Ukraine on terms favourable to Russia, combined with an American withdrawal from NATO member states in Eastern Europe and the de facto abolition of the US security guarantee for Europe – in place since 1945 – would have severe economic consequences for EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe. Foreign direct investment and economic growth would suffer greatly, plunging the entire region into a new era of insecurity and economic uncertainty.

For the EU member states in Western Europe, the definitive end of the post-Cold War peace dividend would exacerbate already ballooning public deficits, likely necessitating cuts to social spending and the welfare state as well as increased borrowing in addition to deepening domestic political divisions and further alienating electorates.

For Ukraine, the consequences would be nothing short of a nightmare. Reduced to a de facto vassal state of Russia, the country’s hopes for meaningful reconstruction, a prosperous economic future, EU membership and full national sovereignty would be crushed. Indeed, Ukraine could become little more than a colony, whose raw materials are exploited by both Russia and the United States. Meanwhile, the prospect of mass emigration to the EU in search of a better life would accelerate Ukraine’s already alarming demographic decline, further weakening its long-term prospects.

Russia, by contrast, stands to benefit economically in such a scenario, even though it would need to subsidise the newly occupied territories for decades to come. While growth may initially slow due to reduced public spending on soldiers’ salaries and compensation, the medium-term outlook could improve with the lifting of US sanctions.

Restored access to American technology for oil and gas extraction, along with high-tech components (e.g. semiconductors), would help to reverse the effects of the current Western embargo. If the United States were to lift economic sanctions on Russia, pressure would mount on the EU to follow suit.

In any case, a rapprochement between the United States and Russia would only present bleak prospects for Ukraine and Europe.