Trump’s trade conflicts will see no winners – and maybe even one unintended loser

12 March 2025

Donald Trump is aggressively pursuing his “America First” policy by announcing various tariff increases – which are often later withdrawn or postponed, leading to significant uncertainty. On 12 March, tariffs on aluminium and steel derivative products enter into force. In any scenario, the greatest burden will be borne by the US itself

image credit: unsplash.com/Library of Congress

By Oliver Reiter and Robert Stehrer

There is one thing Donald Trump cannot be accused of: not keeping his election promises. Even at the beginning of his second term in office, his administration has implemented controversial measures – including in trade policy. By threatening or imposing tariff increases, Trump is trying to force political concessions from Colombia, Mexico and Canada – such as in the areas of migration or the fight against drugs. Recent actions include: the escalation of the already smouldering trade war with China by increasing tariffs on Chinese imports to 20%; the recently announced tariffs of 25% against Canada and Mexico (though these have once again been postponed; tariffs of 25% on aluminium and steel imports against all trading partners, which will enter into force on 12 March; and ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on products for which US import tariffs were previously lower than those of partner countries on imports from the US, which are to be introduced within 180 days and will target countries with a trade surplus with the US.

Tariffs currently in place

To put these announcements into broader perspective, we compare the actual tariff rates applied. One of Trump’s central economic arguments is that the US has lower import tariffs than its key trading partners. He claims that – combined with differing regulations, such as the European value added tax (VAT) – this contributes to a high trade deficit. According to his logic, higher import tariffs should reduce imports, boost domestic production and encourage foreign companies to relocate their manufacturing to the US. However, the argument that tariffs in Europe are generally higher than in the US is only partially valid.

Calculating a single average tariff rate is challenging due to methodological limitations. In any case, according to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the average tariff rate imposed by the EU on US imports is 4.5% for industrial goods and 14.7% for agricultural goods, while the corresponding US tariff rates on EU imports are 3.9% and 7.5%, respectively (see Table 1). The US faces tariffs of 12.2% on agricultural goods and 6.0% on industrial goods when exporting to China, whereas China faces duties of 4.8% for agricultural goods and 4.0% for industrial goods when exporting to the US. For more detailed product categories, see Figure 1.

Although the US does face some higher tariffs on average, the differences – particularly for industrial goods, which make up the bulk of trade – are relatively small. Consequently, the introduction of reciprocal tariffs, as announced, would only result in a limited overall increase in tariffs.

Bilateral tariffs against main trading partners 2022, in %

Average applied customs tariffs according to the most-favoured-nation principle, 2022

Insights from a standard trade model

In our quantitative assessment, we focus on the already announced tariff increases and model their impact on real incomes in the US, the EU and China. We use a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model based on the Caliendo & Parro (2015) framework,[1] incorporating data from the most recent OECD inter-country input-output database. Such models, which assume full employment, simulate long-term economic outcomes. Consequently, other important factors like the increasing uncertainty, changes in investment behaviour and the general threat to the rules-based trading system are not considered.

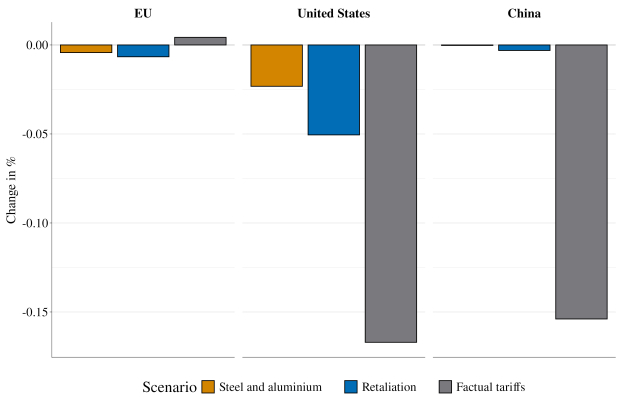

First, we present the results of the US tariff increase to 25% on various aluminium and steel derivative products (approximated by the metals industry) applied to all trading partners. In the second scenario, we examine the effects of retaliatory measures, where all affected partner countries impose a reciprocal 25% tariff on US exports in this industry.[2] Third, we analyse the impact of the tariff hikes already in place. In addition to US tariffs on aluminium and steel derivative products, we also include a 20% tariff on imports from China. In response, China imposes a 15% tariff on US mining imports and increases tariffs on machinery, vehicles and transport equipment by 10 percentage points. Additionally, China enforces the announced 15% tariff on agricultural imports from the US.

Figure 2 illustrates the estimated impact of these scenarios on real wages. In the US, real wages would decline the most, ranging from a 0.03% decrease in the first scenario to a 0.17% decrease in the ‘factual’ scenario. These negative effects are driven by rising import costs, which in turn lead to higher domestic prices. [3]

Simulated changes in real wages, in %

Source: Own calculations

In China, real wages are projected to decline by approximately 0.15% in the ‘factual’ scenario due to the US tariff increases on Chinese imports and the effects of retaliatory measures, which further contribute to price increases in China.

The EU is largely unaffected in these scenarios given the relatively small size of its metals industry. In fact, due to trade diversion effects, there are even marginal positive effects in the ‘factual’ scenario for the EU as a whole and for some individual EU countries.

Summary

Given the unpredictable and erratic approach of Donald Trump, it is impossible to accurately predict how the trade conflict triggered by the US announcements will ultimately develop. Nevertheless, simulation results from a standard trade model suggest that the tariff increases implemented so far – on aluminium, steel and Chinese imports – along with China’s retaliatory measures will have only relatively small negative impacts on real incomes. However, the above-mentioned results on the impact of tariff increases indicate that there are no winners in such trade conflicts. In fact – as evidenced by rising inflation, a deteriorating business cycle and falling stock markets – the greatest burden will be borne by the initiating country. And in this case, that is the US.

Footnotes

[1] Caliendo, L. & Parro, F. (2015). Estimates of the trade and welfare effects of NAFTA. The Review of Economic Studies, 82(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdu035

[2] The EU just recently announced retaliation measures amounting up to €26bn of US goods (see https://www.ft.com/content/69f582a6-3cec-4858-b115-3a24329102b4).

[3] Taking tariff income into account, the total welfare effect for the US would be slightly positive.