Turkey: Economic challenges mounting

11 November 2021

Although the economy has come through the pandemic relatively well so far, the risks are mounting, owing to erratic policy choices, high inflation and the tumbling lira

image credit: unsplash.com/Fatih Yurur

This is an adapted English translation of an article originally published in Der Pragmaticus

- Turkey’s economy is emerging from the pandemic in relatively good shape, but rising global interest rates and erratic domestic monetary policy are again threatening the country’s macro-financial stability.

- To escape from the current boom/bust cycle, economic policy must become more orthodox and predictable. This may hurt growth in the short term, but it will allow the Turkish economy’s underlying strengths to come to the fore.

- Turkey remains an important partner for the EU, due to a high level of economic interdependence and its important strategic location. It is in the interests of both sides to cooperate.

Over the past two years, even as the global economy has been severely battered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions imposed to combat it, Turkey has emerged as something of a success story. Of the 23 economies of Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE) covered by wiiw, Turkey’s was the only one to post positive growth in 2020, and it will achieve the fastest rate of expansion this year as well. Yet, although this impressive performance partly reflects the traditional resilience and adaptability of the Turkish economy, it has also been heavily supported by unsustainable credit growth that will exacerbate existing economic imbalances. As developments over the past few weeks have hinted, the economy now appears to be headed for a more difficult period.

An unbalanced economic model

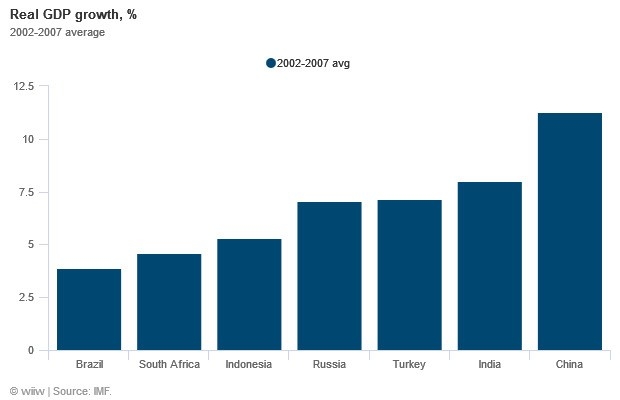

For most of the time between 2000 and around 2015, Turkey was one of the favourite emerging markets for foreign investors. Generally strong economic growth, NATO membership, EU accession candidate status and a conservative fiscal policy earned Turkey the approval of foreign banks, portfolio managers and rating agencies. At the beginning of the new millennium, following the global recovery from the repercussions of the bursting of the dot com bubble, there was a generous flow of capital into Turkey from abroad. The economy grew robustly, with gross domestic product increasing by an average of 7% annually between 2002 and 2007. Of the major emerging markets, only China and India posted better performance.

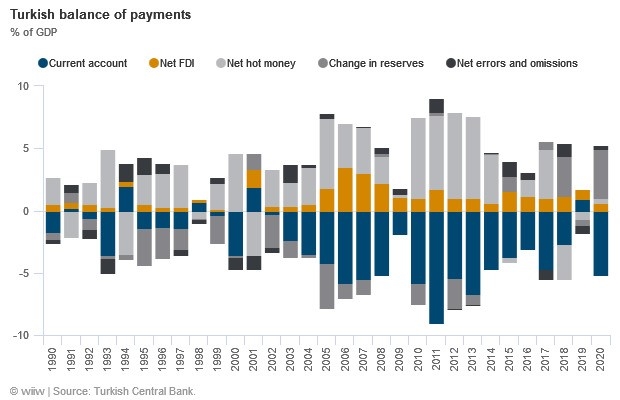

However, the Turkish boom concealed a serious flaw: the economy was too dependent on so-called ‘hot money’ from abroad. Hot money is essentially short-term capital in the form of portfolio and other investment that can exit an economy as quickly as it arrives. As the chart below shows, from 2003 onwards, Turkey started to post consistently large current account deficits (blue bars), financed primarily by net hot money inflows (light grey bars). More stable foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows (orange bars) provided a much smaller share of the financing. The Turkish growth model therefore became one that hinged on current account deficits, financed by short-term foreign debt. In good years for the global economy – for example 2002-2007 or 2010-2014 – this did not cause huge problems. But when difficult times arrived, and foreign capital flows dried up, the Turkish model left the country badly exposed.

Political risk increasing amid a deteriorating relationship with the US

An economic model that is reliant on global capital flows requires not only favourable conditions on the global markets, but also political stability. Foreign investors can easily be spooked by perceived increases in political risk. Unfortunately, the political risk in Turkey has been high and increasing over the past decade. This applies to both domestic and foreign policy. Increased pressure on the formally independent central bank is a particular issue for foreign investors.

Most damaging of all has been the deteriorating relationship with the US. Turkey’s reliance on external dollar financing renders it extremely vulnerable to potential US sanctions. The detention of an American pastor in Turkey in 2016-2018 was particularly damaging. Nothing worries investors as much as the threat of US sanctions against Turkey, and this concern contributed heavily to the lira collapse of 2018.

An economy prone to increasingly wild swings

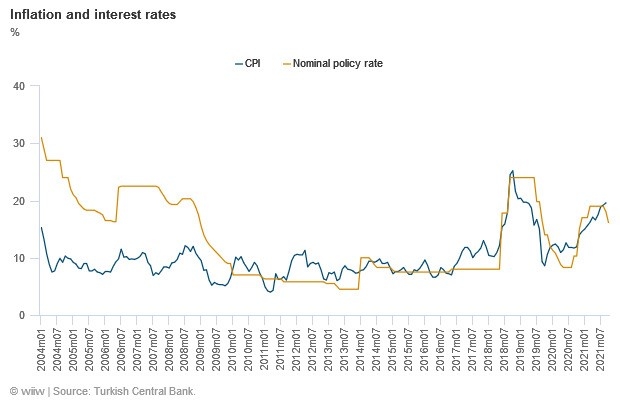

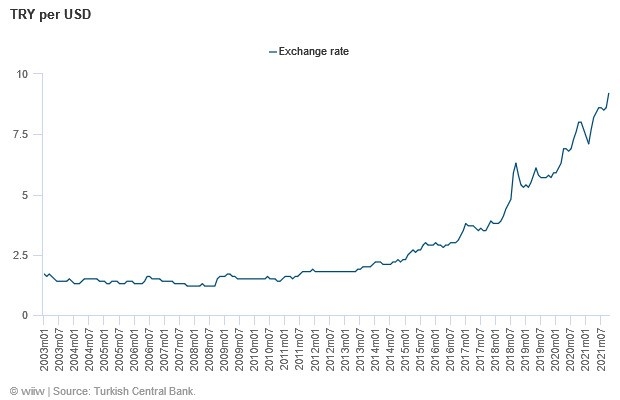

The inherent vulnerabilities of the Turkish growth model have been exacerbated in recent years by a government determined to keep economic growth high at all costs. Until 2009, the central bank generally ran a tight policy, with the short-term rates positive in real terms; but in the years since, that has changed quite dramatically (see first chart below). The central bank has been keeping interest rates very low and often negative in real terms, and has consistently surprised the market with overly dovish policy (including very recently). Although this stance has stimulated short-term credit growth, including during the pandemic, that expansion has come at the cost of rocketing domestic inflation and an ever-weaker lira (TRY) (see second chart below).

Especially since 2018, Turkey has been stuck in a downward spiral of often low or negative real interest rates, a weak lira and high inflation. Periodically, the central bank has to react: it tightens interest rates and the country suffers a growth slump. What is worrying is that, as the coils of the spiral become tighter, so the intervals between crises become shorter. In 2018-2020, real GDP grew by an average of less than 2%. This is very weak by Turkish standards. Although growth has been stronger in 2021, it has relied on short-term factors that will not last.

Tightening global credit conditions make a change of course even more necessary

The main problem Turkey now faces is inflation in the global economy, including in the US and Europe, and the way in which other central banks react to it. For about a decade, persistent above-target inflation has not posed a serious threat in developed countries, so that global monetary policy has been able to remain ultra-loose by historical standards. That has meant that countries with large foreign currency borrowing needs, like Turkey, have managed to keep rolling over these debts at low rates. However, as the Fed starts to become more hawkish, this will change. In 2013, the ‘taper tantrum’ caused major volatility in Turkish financial markets, and the Fed has just announced that it will start tapering its asset purchases before the end of the year.

There may be worse to come in 2022, if inflation in developed countries continues to prove less transitory than the Fed and the European Central Bank had originally expected. In the past, Turkey’s economy has proved much more resilient than many expected. Moreover, current balance of payments fundamentals look somewhat healthier, reflecting a boom in goods exports (no doubt helped by the cheaper lira). Nevertheless, with short-term external debt totalling $126.9bn at end-August according to the central bank (of which 41% is denominated in US dollars, and a further 25% in euros), the risks are significant.

For the economy to emerge from the downward spiral, Turkish policy will have to allow monetary policy to do more to keep inflation in check. As soon as Turkey leaves the loop of instability, other strengths will come into play: its relatively diversified economy, its large domestic market and its young, growing population. The downside of a restrictive monetary policy is that the current credit-financed growth could be curbed. What would be good for the country in the long run comes at a cost in the short term.

What is at stake for the EU

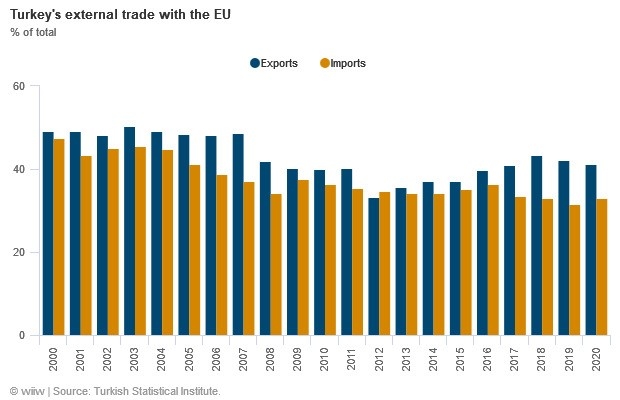

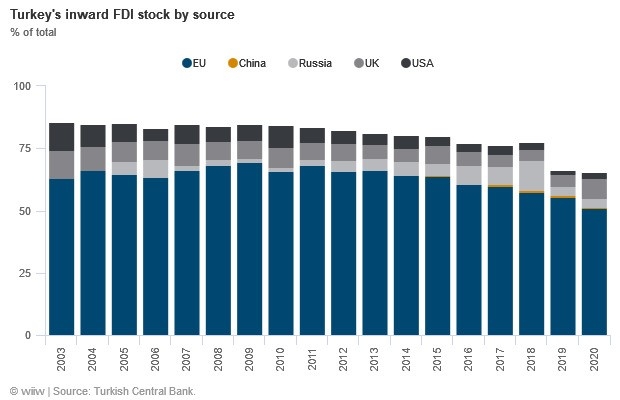

In the US-Turkish relationship, Washington holds almost all the cards. But Turkey’s relationship with the EU is much more one of interdependence. Over 40% of Turkish exports and around a third of imports are to/from the EU, and the EU is responsible for more than half of all foreign investment in Turkey (see charts below). Conversely, the EU needs Turkey – and not only as a partner in its refugee policy. As the (literal) bridge between East and West, Turkey occupies an extremely important strategic location from an EU perspective. Given the instability in the Middle East and the growing influence of Russia and China in Southeast Europe, it is in the interests of both Turkey and the EU to work together.

It is true that Turkey may never be an uncomplicated partner. Further challenges and difficulties are to be expected. However, the EU and Turkey are bound together. Whatever one may think of the current government in Ankara, a more serious crisis in the Turkish economy or a breakdown in political and economic relations between the EU and Turkey would be disastrous for both sides.